archy, mehitabel, and James Whitcomb Riley

by Don Swaim

On a booking expedition to Lambertville, New Jersey, I happened upon two poetic gems at the venerable Phoenix Bookshop (now, sadly, extinct). The contrast between the two authors, whose lives overlapped, couldn't be more vivid.

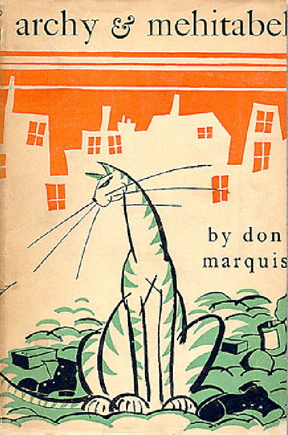

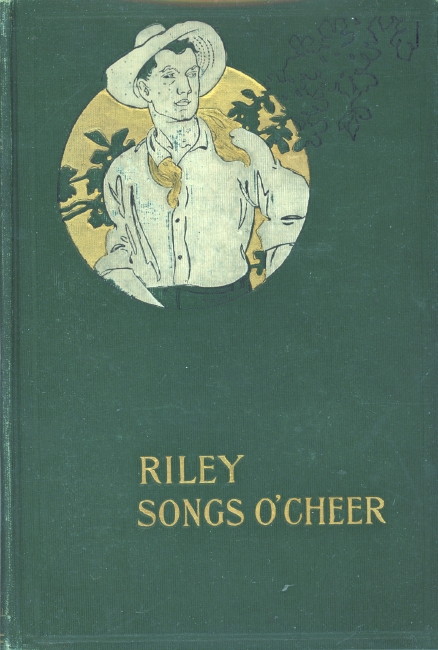

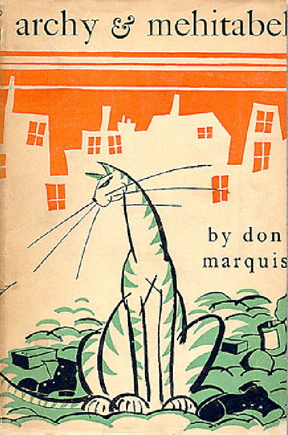

The first book was James Whitcomb Riley's 1905 Songs O'Cheer. The other was a 1950 reprint of the lives and times of archy & mehitabel by Don Marquis, originally published in 1927.

Both Riley and Marquis were Midwesterners. Riley was born in 1849 near the town of Greenfield, Indiana, Marquis in 1878 in Walnut, Illinois. Both were newspapermen. Riley was a reporter for the Indianapolis Journal before turning himself into a full time poet. Marquis worked for several major newspapers prior to landing a job as a columnist for the New York Sun.

Riley's homespun poems, much in dialect, led him to national fame. More than 35,000 people passed his bier following his death in 1916, and the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp to honor him in 1940. Marquis experienced a series of family tragedies and suffered from several debilitating strokes before his death in 1937.

Marquis' column, "The Sun Dial," gave him an outlet for his biting social criticism, manifested best by his creation of archy, a cockroach, and mehitabel, an alley cat. archy writes commentaries on a typewriter but can't manage the typewriter's shift key, so he must spell out or ignore punctuation; thus, the lack of caps.

Marquis, Riley

Marquis, Riley

Riley's work is, by today's standards, painful to read. Sometimes difficult to follow due to the phonetic spellings, much of it is narrated by a "Benj. Johnson," a pseudonym for Riley himself. Because we now have the ability to actually hear accents and dialects (via radio, TV, film , and the Internet), which Riley didn't, it would be absurd to apply them in today's prose -- and the subject of ridicule. Here's a taste of Riley:

I ain't, ner don't p'tend to be,

Much posted on philosofy;

But thare is times when, all alone,

I work out idees of my own.

And one of these same thare is a few

I'd like to jest refer to you--

Providin' that you don't object

To listen clos't and recollect.

The odd spellings are, of course, Riley's inventions, and his cracker-barrel sensibilities were beloved by an America that in Riley's time was mostly rural.

One important critic, however, despised Riley's work. He was Ambrose Bierce, who pulled no punches when he said this of Riley:

In the dirt of his "dialect" there is no grain of gold. His pathos is bathos, his sentiment sediment, his "homely philosophy" brute platatudes--beasts of the field of thought. His humor does not amuse. His characters are stupid and forbidding to the last supportable degree; he has just enough creative power to find them ignoble and leave them offensive. His diction is without felicity, his vocabulary is not English.

Marquis, the urbane, big-city columnist, was the antithesis of Riley, and a sophisticated joy to read even today. While Marquis has his own affections (no punctuation) there are, thankfully, no phony Riley-style dialects. Here's a pearl from archy in the 1950 reprint:

i once heard the survivors

of a colony of ants

that had been partially

obliterated by a cow's foot

seriously debating

the intention of the gods

toward their civilization

or

how is tricks still in the

ring archy she said and still a

lady in spite of h dash double l

always jolly

archy also spells out words that might have been offensive at the time, such as "hell" ("h dash double l"). Some might claim that the words of archy and mehitabel aren't poetry in the strictest sense, but I view it as free verse on a high level.

One might suppose that in 1905, when Riley's Songs O'Cheer was published, dialect in prose and poetry could be useful because there were few recordings of actual voices, nor were there radio or motion pictures with sound. Still, Riley's maudlin, mawkish, sentimental, country corn is hopelessly anachronistic.

We were not an educated nation in the days of Riley and Marquis. Census figures cited in a 2007 paper for the Study of Labor found that of all Americans born in 1900, only twenty-six percent graduated from high school and just five percent earned college degrees. It would be fair to say that Riley's poetry struck a popular chord while Marquis' work was favored by a discriminating minority.

However, for all their contrast, both Riley and Marquis secured a niche in the history of American letters.

Update. On a sweltering July day, 2013, in the final throws of a heatwave, I navigated harrowing I-95 to Philadelphia's well-worn Port Richmond neighborhood, which is in the shadow of that motorized Interstate monstrosity. At the enormous Port Richmond Books, in a former silent-movie theater -- long silent -- boasting of a stock of 200,000 books in various states of quality, I encountered a legitimate first edition of archy & mehitabel, 1927. It lacked the dust jacket and had a former owner's inscription, but at $35 it was decent enough. This edition is different from the later archy & mehitabel editions: it includes only the first of the three-book archy series, no illustrations by George Herriman, and no introduction by E.B. White. Identifying the first editions of Don Marquis can be a bibliographer's nightmare, especially the archys. I was happy to acquire this artifact of the 1920s. If anyone visits Port Richmond Books, wear old clothes and carry a flashlight (nooks and corners lack illumination). One might find some gems buried in the heaps of books. Here's the original first edition dust jacket of 1927:

_________________________________

Excellent Don Marquis site: here

Another excellent Don Marquis site: here

A James Whitcomb Riley site: here

|