In the fourteen years in which she anchored at WCBS, including afternoon drive with the likes of Tom Franklin, Gary Maurer, and Harvey Hauptman, Rita Sands got to know the station's chopper pilots, both on and off the air. As a licensed pilot herself, who once headed public affairs for the Eastern Region of the FAA out of JFK, who better than Rita to tell both the helicopter story and her own? --DS

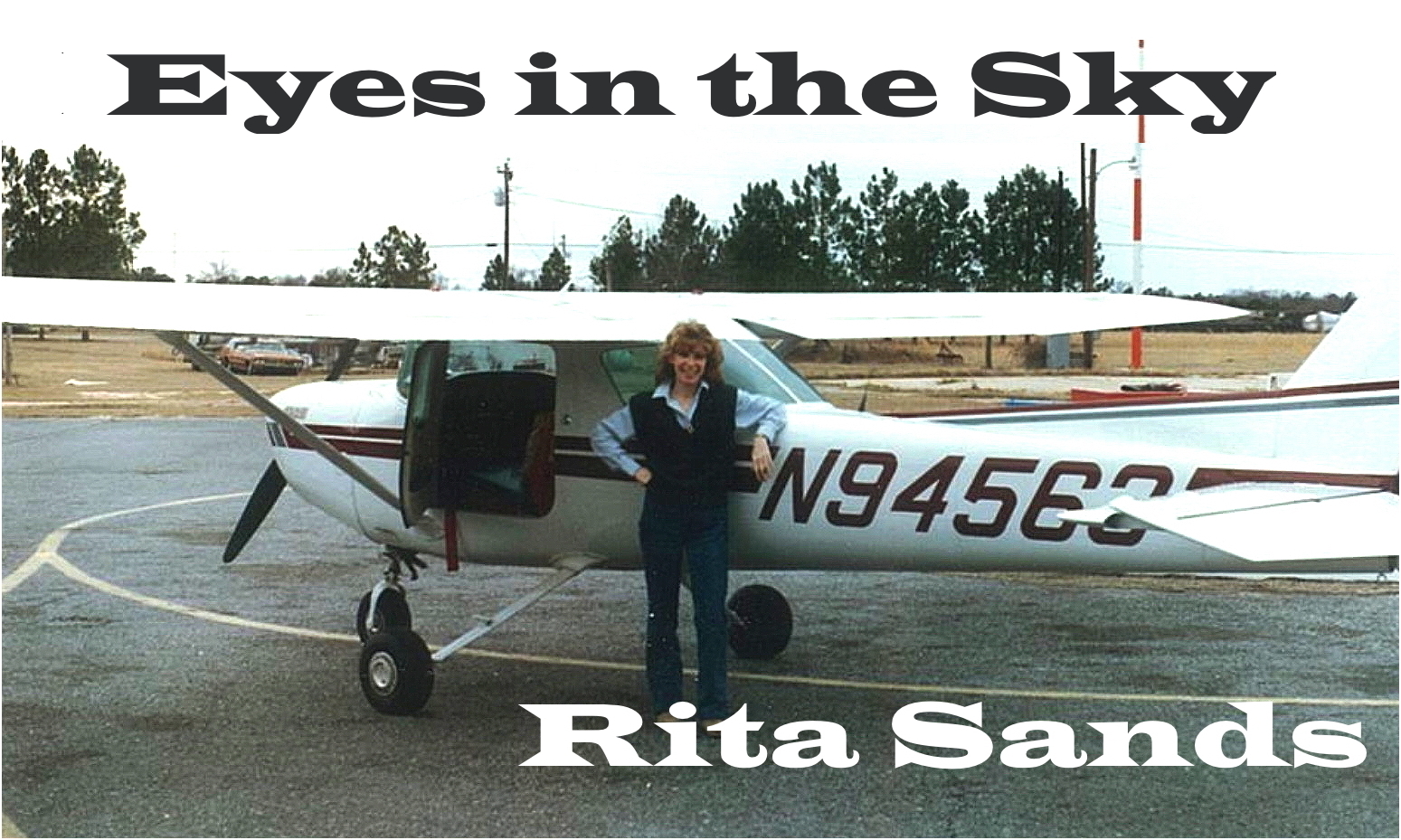

Rita and Cessna

________________________

Working in news, particularly in live radio news, especially in the way it used to exist in the early 1970s, you discovered every day how much more you are capable of learning and executing, more than you would have ever thought possible, and it surprises you in a very exciting way.

In the early 1970s I was hired as the first woman anchor at WCBS News Radio. I was used to the limits that people placed on me. But here, at News88, an intense place of information and traffic, both on the ground and in the air, there were people all around who could teach you by example as well as what was simply required of you. You had to step on the conveyer belt and hold on and contribute.

Within that learning curve was a thinking work cycle you lived by, survived by: a sequence of what just happened, what to make sure to remember from it, while maneuvering within the parameters of what is happening now, and preparing in the back of your mind for what's coming up, and fast. The clock was the master, and the mission was keeping the radio audience running with you, wide open to the voices and sounds that convey an endless road of information and thoughts that have impact on their world.

It's both very hard and inexplicably rewarding, this 360 degree awareness. The News88 helicopter pilots, Neal Busch and Lou Timolat, called it "situational awareness" as the engine runs. If you're any good, nothing sneaks up on you, and you "land in a safe place," every time, to begin the cycle again.

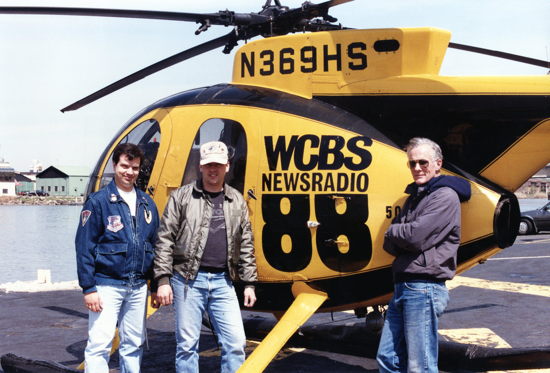

Neal Busch (l) Lou Timolat (r)

I don't think this would have happened to me in any other place. It was at this radio station, in this era, with these people, at just the right time of my development. I picked up speed and understanding every day, working alongside an incredible and seasoned news staff, reporters, writers, editors, producers, engineers, the news directors, the sales people, every single person there made an impact, and we all had to monitor the product, what went out over the air. You had to keep listening and evaluating.

These were pre-computer days, and we first made contact with written news from teletype machines, which chugged along in a really loud incessant way, in a wire room, which every radio station had. It offered story after story written by news service reporters. You'd read through it all and type out headlines and scripts for air on your manual typewriter, all overseen by the executive producer, who, when a story would break would often run the length of the typewriter room, through two doors to get into the air studio to hand deliver to the anchor, or the reporter sitting near you, to give an update or a bulletin, that could change everything. But never at the cost of missing what the clock demanded. It could be meeting the scheduled time to play commercials, pre-recorded or those we had to read live for sponsored feature programs, and the inevitable network join, precisely on the hour, or at other join times throughout the hour.

Over the years I worked with many different co-anchors at different schedules on the air. Each partnership was different and so too the balance of the working relationship. There was a lot to learn, and in the end, what could be better. I valued each and every partner and thank them to this day.

WILBUR & ORVILLE

WCBS Radio's chopper fleet dates back to "Wilbur and Orville." No, not the Wilbur and Orville, the Wright brothers, but two flying traffic reporters dubbed Wilbur and Orville, one spotting traffic on Manhattan's West Side and New Jersey, the other the East Side and Long Island. Someone at CBS must have thought the lame notion to name the pilots after the two aviation pioneers a clever idea in the days before the station switched to all news in the summer of 1967. Long-time staffer Harvey Hauptman describes it this way:

Pat [Summerall] was WCBS's morning man before the station went all news. He was the host of the show that had been Jack Sterling's spot on the schedule and, as Pat later told me, "I was a disk jockey who didn't know anything about music." But, with a very able staff -- John Chanin was the producer -- Pat was billed as "Super Summerall." The program's hokiness also referred to the two helicopter pilots covering traffic each morning as "Wilbur" and "Orville." Unfortunately, I don't remember their real names.

As a fledgling broadcaster, Bob VanDerheyden, who worked on both the Jack Sterling and Pat Summerall shows (and was later program director of WCBS-FM), compiled traffic reports in both morning and afternoon drive. VanDerheyden doesn't recall the actual names of Wilbur and Orville, but he remembers the station's first chopper pilot as Bob Richardson who joined WCBS from Chicago.

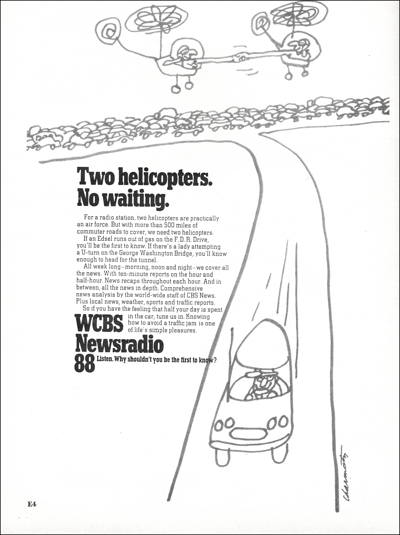

Newsradio 88 ad in Newsweek, 3/18/68

Click to enlarge

Based on biographical information from the Helicopter Association International, of which Richardson was president from 1966 to 1969 and later executive director, he learned to fly fixed wing and rotary aircraft in the Army. Leaving the service after seven years, he joined Butler aviation as a helicopter pilot in Chicago. Butler named him chief pilot in 1959 and general manager in 1962.

Three years later, he was transferred to LaGuardia where he took over all of Butler's helicopter operations in New York and Chicago. At LaGuardia, he launched the first airborne traffic service for WCBS, which included reports from dual choppers in both morning and afternoon drives using the skills of several pilots, who were known generically as "Wilbur" and "Orville." After Butler left the helicopter business, Richardson became president of the ill-fated Washington Airlines.

Bob Richardson

Bob VanDerheyden flew with Richardson, a newcomer to New York, for a couple of weeks to familiarize him with the area's roads, highways, and landmarks. They dubbed Richardson's chopper the "Help-o-Copter."

VanDerheyden is now [2015] an owner of a group of stations based in Scranton, PA, and stays in the groove by doing a regular doo-wop show on WWRR FM/104.9 Wilkes Barre-Scranton. --DS

|

It wasn't long after I joined WCBS that I took great interest in what our news and traffic helicopters were doing. They were doing a lot that not only impacted and updated our stories if they could be witnessed by air, but their primary mission was providing directly verified traffic problems that helped a huge number of commuters every day. Just that "sounder" that preceded a live report from one of the WCBS helicopters made all of us sit up and take notice.

Through the years the News88 helicopter crews were essential to the widening of live and on scene coverage of all kinds of news. Our own pilot reporters were the best, and respect for them kept growing every time we learned more about what exactly they had to do up there in a single engine aircraft weaving through a crowded sky yet bound by an approved corridor of air that would remove the burden of having to check in with ATC (Air Traffic Control) every few minutes.

Our helicopter pilots had to maintain separation from other aircraft at pre-approved altitudes through corridors of air over Manhattan known as the VFR corridor starting at the George Washington Bridge to the Verrazano Narrows Bridge.

Sands with a New Jersey National Guard member

aboard a tanker flyer during a mid-air refueling mission 35,000-feet over Maryland

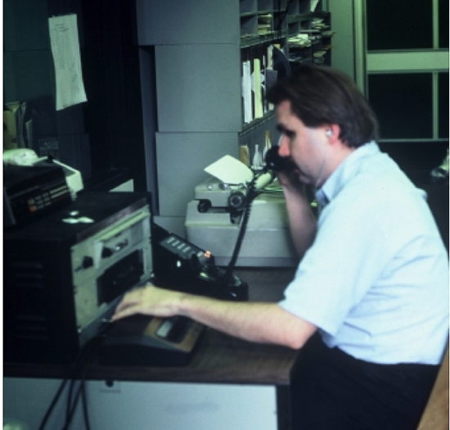

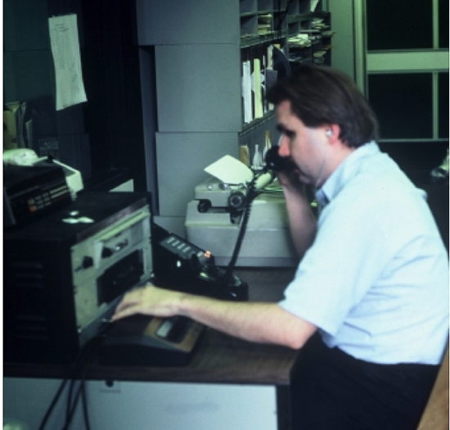

Communicating to base and to the public were demanding works in progress, throughout every day. Some very smart people behind the scenes -- the engineering staff -- kept the lines of communication open and clear. Here's some insight into how their work went on:

The two-way radio system for the helicopter pilots to communicate to both base and to the public, often needed fixes and improvements. Engineer Barry Siegfried, who joined the station in 1975, was a quick study with everything the "chopper" needed to be in touch at all times, deliver live reports and receive messages back. He knew how to evaluate problems with what looked like bunches of wires and connection points, and had complex solutions within minutes. Earlier attempts had been made to rely on wide band studio audio quality, with a required wideband Marti transmitter, "which was really an RPU remote pick up," according to Barry, who said it "suffered from more path interference, which became intolerable."

Barry Siegfried

Eventually they put a real two-way radio back into the chopper with updated repeater equipment. The new system improved drive time helicopter reports. Though it was challenging, he said, when they added "HD" to their AM transmitter and the programming on their AM air had to be delayed by about 9 to 10 seconds to match the digital delays that Barry described as inherent with the production of the HD signal. Yet this meant that the chopper broadcaster could no longer listen to the AM signal for his off-air cue because it was no longer in real time. So they devised a cueing system, which involved another UHF frequency, and Barry figured it out.

A BRIEF HISTORY

OF THE NEWSRADIO 88 HELICOPTER TEAM

1. Bob Richardson, from Chicago, who worked for Butler Aviation's helicopter branch, became the station's first chopper pilot sometime after 1965, before all-news, which began in 1967.

2. Since the station flew dual choppers in AM and PM, Richardson scheduled several pilots, including Neal Busch; thus, the Orville and Wilbur names, which, thankfully, was discontinued.

3. After Butler Aviation left the helicopter business, ca. 1970, the company was taken over by NorthEast Helicopters, which in turn was acquired by Island Helicopters. Busch and Lou Timalot were retained as the primary broadcasters.

4. In 1974, Busch and Timalot formed their own company, Luftspiegel (German for Air Mirror).

5. Tom Salat, a corporate pilot for CBS and a former air traffic controller, often did fill-in helicopter reporting.

6. In 1984, Busch bought Timalot's interest in Luftspiegel and Busch negotiated a new contract with WCBS.

7. Terry Raskyn was Busch's first broadcaster under the new contract, flying with pilot Mike Dillon.

8. A year later, Raskyn was replaced by Donna Fiducia, who left in November 1986 after NBC's fatal helicopter crash.

9. Replacing Fiducia, was Joe Nolan, a reporter who flew with pilots Ed Baker or Mike Dillon until Nolan left for Shadow Traffic in 1999.

10. Tom Kaminski replaced Nolan, and after Busch's own departure in 1999, continues to fly with pilot George Lougnot.

Neal Busch, who helped to compile the above list, writes:

When I started broadcasting, I think in January 1967, Bob Richardson (and I think he was from Chicago) was the helicopter guy for Butler Aviation, which was the FBO [Fixed Base Operator] at the Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia. The broadcasters were called Orville and Wilbur because there were two helicopters up AM and PM, and so we really needed a lot of pilots and broadcasters and everyone was just sort of feeling their way to see how this thing was going to work. Of course the need for two helicopters was to try to own traffic info credibility, because Fred Feldman was Sky King in New York at WOR, and he was very, very good. So there was Bob Richardson, another pilot broadcaster he brought to New York from Chicago, whose name I can't remember, and about six or seven other guys who flew on a schedule that Richardson drew up. Anyway, it wasn't too long, I think only a few months, before the station decided to introduce the pilots by their real names. [rather than Orville and Wilbur]

At the same time, we would fly other jobs: I once picked up Nelson Rockefeller at his estate in Pocantico Hills, and flew him to Jackie Robinson's house in CT for a meeting of some sort, and weekends in the summer there was a constant stream of flights out to the Hamptons.

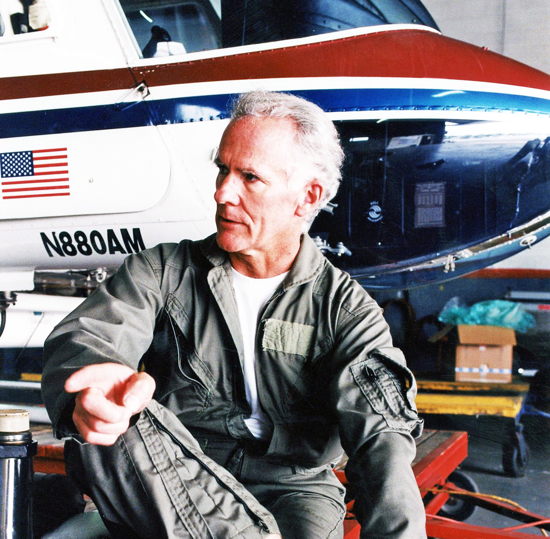

One other very sweet note: WOR, our traffic competitor from the beginning, decided to get out of the helicopter traffic business in 1993. Their helicopter, a Bell Jet Ranger, had been especially outfitted for traffic broadcasting, like extra sound proofing, and I coveted that machine. Especially since Fred Barbieri [a CBS technical supervisor] and the other tech guys were always bitching about how noisy my helicopter was and how quiet WOR's was.

Well, in June of 1993, I negotiated with the people at WOR about owning that helicopter, and soon thereafter, George Meade ended up flying "his" helicopter to my heliport, handing me the keys. It didn't take long to change the N number from WOR to N880AM. So for the last six years of flying it couldn't have been safer or more fun. (Barbieri still bitched)

|

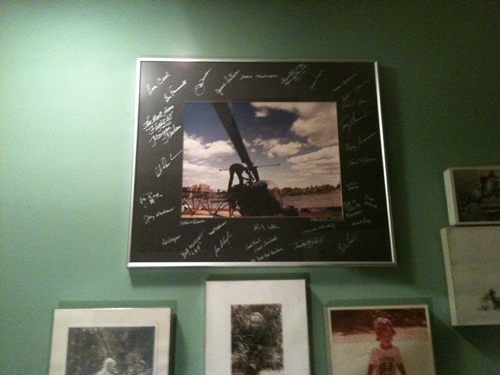

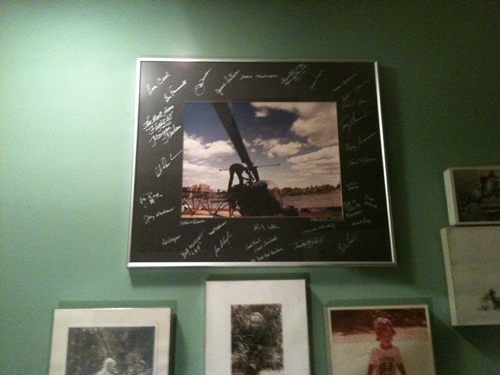

One day, pilot Lou Timolat who knew of my interest in learning to fly, offered to meet me at the eastside heliport for his pre-flight work up. While he was standing on top of the helicopter, checking the base of the rotors, and all the wiring and connections up there, I took a photo of him.

When Lou was nearly ready for take-off, and as I sat next to him to his right, he asked that I run through a safety exercise. He had me close my eyes, and without looking, find the latch to disconnect my seat belt, then to reach for the cabin door handle and open it, before exiting the craft to swim to safety. Darkness under water is a critical influence on panic and reduces the odds of a passenger becoming a survivor should the worst happen. So exercises like these, if done regularly, help a passenger to respond automatically and act quickly in releasing constraints, improving the odds of surviving a crash.

Timolat, photo by Sands

In the photo of Timolat's helicopter at the east side heliport [above], you can see in the distance an approaching plane. Lou, who always has such interesting things to say, told me how my eyes would fool me if I stared straight ahead looking for that oncoming aircraft. "Because it won't register in your vision," he said, explaining there's a blind spot in the center of the pupil called "Fovea Centralis" in the middle of the retina where the optic nerves are attached. In the middle of the retina is a small dimple called the Fovea, and in low light especially, it creates a blind spot, something especially important for pilots to remember. Instead, Timolat says the pilot sweeps his vision to the left and then to the right, so he will in fact see that aircraft if it's flying straight ahead or straight for him. And now that's something I will never forget.

That picture of Lou, atop his helicopter, was the photo brought to his retirement party when he left WCBS, and everyone there signed it. It's now at home with him in Connecticut. I'm proud of that picture because it gave him a great memory; it celebrates him "on top" of his game, on a beautiful day, at a heliport that always sent him on his way, safely.

Sands' photo of Timolat, framed & signed by WCBS staffers

In those days I was never without my camera. Many of my pictures taken at News88 of the people who worked there found a home eventually at Don Swaim's WCBS Appreciation Site, just where they should be. Don's website keeps the tribute going for a special era of radio and radio news and the people who gave so much to it, as Don still does.

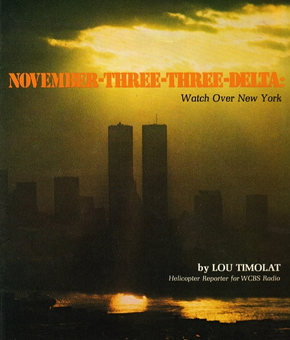

LOU TIMOLAT & NOVEMBER-THREE-THREE-DELTA

Watch Over New York

Lou Timolat flew afternoon drive for Newsradio88 armed with his piloting skills, perspective of traffic, and a camera with a wide-angle lens. November-Three-Three-Delta, Lou's book title, was shorthand for N6733D, the WCBS chopper's serial number. Timolat's often breathtaking photos from the sky filled his book, published by Chatham Press in 1974 when he was thirty-one.

At one time, the WCBS helicopter reporters were allowed to report only on traffic, something to do with AFTRA's union contracts. That changed with this memo from the station's assistant news director: "According to labor relations, our pilots are under no restrictions in the nature of reporting they may do. That means that in addition to routine traffic reporting, they can describe fires, explosions, sinking ships, crashing airplanes. etc."

Lou Timolat, in his book, proves to be a poet of the air. He writes:

To many people, a traffic fatality means the high speed crash or a single car; an anonymous individual racing home too fast on some remote road nods asleep or loses control on a curve. The accident is unseen and unheard, and is discovered long after the fact.

What a grim contrast this is to the reality I observe daily. Week by week accidents, their location and severity are predictable and apparently irrestible. Witnessing this chaos is an experience hard to accept, even for one who is now more or less accustomed to the probability of violence. Regiments of motorists seem to move below me like enormous armies and must inevitably give up some of their number as casualties of wrenching conflicts. The scars and fresh wounds of these conflicts are visible daily, and as I see the worst of them, I feel disgust, anger, and helplessness.

Timolat's book is out of print, but its first chapter, with all of its beauty and nitty gritty, is posted HERE --DS

|

Tom Salat, a military-trained helicopter pilot, as were Lou and Neal, initially worked for both CBS corporate aviation based at Westchester County airport, but was also a back up pilot for the News88 traffic helicopter team, doing his share of broadcasting reports over New York.

He told me that piloting a helicopter is like standing on top of a basketball, balancing in all 4 directions, not to fall forward, or backward, or side to side. Imagine the precision of it, but without thinking of it every flight, it develops into what Neal Busch calls "exquisite core balance." Even as the pilot keeps moving forward or back, or turning or changing altitude, elevating or descending, weaving through the air, with all that's coming at you, or could be, then it's always back to the basketball, the default position, and hanging there in perfect stability without the guidance of a sophisticated computer, by the way.

Tom was often the personal helicopter pilot for the head of CBS, William Paley and at times, there were also corporate passengers. The helicopter on those forays was a Sikorsky 76B, a much larger and more sophisticated aircraft, with soft seats, wooden beverage cabinets and nice pillows in the back.

Sikorsky 76B

Paley felt very comfortable and safe with Tom as his pilot. He told him so. When the two of them would arrive at some small airport, Paley would frequently ask Tom for a dime so he could make a telephone call on one of those outdoor pay phones. Tom had to inform Paley that they now cost a quarter. So then Paley would ask Tom for a quarter, but still kept Tom's dime. Sometimes together they'd go shopping for flowers called paper whites... Paley just loved paper whites, and Paley would ask Tom if he wanted some. But Tom declined, wondering how he'd explain that to the landing crew back at Westchester, who knew he'd been with Paley.

Tom was invited to Paley's funeral, at a church on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Attendance was by invitation only. Guess what kind of flowers were overflowing in the church? Paper whites. Delicate and fragrant, an unusual choice. But not to Tom.

Sometimes our chief editor would inform the pilots of breaking news that might require their checking it out. We had a traffic "desk" situated next to a wall of mailboxes, near a door that went to the air studios and not far from a long and loud table of clanking typewriters, reporters, writers and anchors typing scripts and headlines for programs coming up.

In this tight little niche of an area one could find Rich Adcock at his post, the traffic desk. Rich was totally blind. Prior to the 90s Rich came in every day by bus from Queens, twice a day, for a split shift, 6 am to 9 am, and then back again for the 4 pm to 7 pm shift, in part "switching" the helicopter to air, or he would type up transit information on one of those manual typewriters, and "walk it" into the air studio. Rich had memorized a detailed schematic of the New York City subway system. He knew every line, and every stop. His work of service to the radio station mattered to him, greatly. He was a soft earnest gentleman, and always knew where to find us, by our voices. But all things eventually change, and so they did for Rich, too. He was let go, and that must have been very hard on him. He passed away a few years ago.

Rich Adcock

The station began to rely on an outside contractor, Shadow Traffic, to provide traffic reports when the helicopters weren't flying. One of Shadow's prominent reporters, Ed Salvas focused on reporting for WCBS giving new stability to an important part of the mission of WCBS.

SHADOW TRAFFIC ON NEWSRADIO 88

by Ed Salvas

I arrived at Shadow Traffic in the summer of 1989, a few months after Shadow moved from its original home in Union to a ninth floor suite in the Meadows Office Complex on Route 17 in Rutherford, N.J.

Shadow served both of the all-news stations in New York, WCBS and WINS, which were fierce competitors at the time. WINS began 24-hour traffic reports a few months ahead of WCBS, but CBS caught up quickly with its "Traffic and Weather Together on the Eights."

The Shadow operation had a horseshoe shaped desk in the center of the room with studios along the outside wall. Four "producers" at the desk worked the phones during drive times gathering traffic information from multiple sources as well as Shadow's own fleet of Chevy Blazers that roamed the streets and highways, reporting via two-way radios. Shadow also had its own chopper that primarily served the operations desk. Both the Shadow and the CBS chopper used a small heliport in Ridgefield.

There were no cell phones, but a few Shadow people had "bag phones," large battery operated phones carried in a suitcase to use on the road. The costly chopper and the fleet of SUV's were gone by the mid-1990s, replaced by cameras at strategic locations.

Shadow also had its own language -- a shorthand of letters, numbers and symbols to describe the road conditions and locations of traffic problems. Some were familiar, like the BQE or NJTP. Some were created for us: B2B (bumper to bumper), OTV (overturned vehicle), > meant approaching an exit or area, NB for northbound, SB for southbound, etc. Announcers had to pass a test to get on the air. TV arrived in the early 90s with the first reports seen on Channel 4 from a camera set up in the operations area.

Salvas

Ed Salvas worked at Shadow on WCBS from 1989-93 and also at New Jersey stations WJLK in Asbury Park, WBUD/WKXW Trenton, WOBM Toms River, WPAT Paterson and WADB Point Pleasant. He is currently a business writer for The Coaster, a weekly newspaper in Asbury Park, NJ.

|

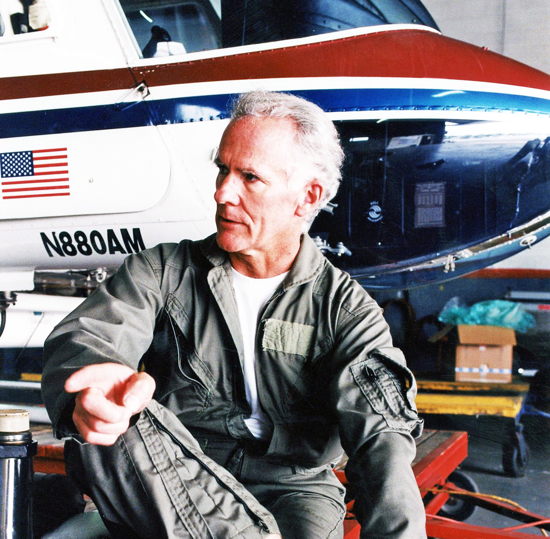

No one doubts that social media will have a profound effect on continued helicopter traffic coverage in major cities, according to pilot Neal Busch. He says the "timing of his whole career was just right," that he can foresee how instant visual computer coverage of traffic tie ups and other commuting problems will replace the system we have now, and that it will actually "be better for commuters who rely on minute by minute information to get to their destinations efficiently and safely." He sees it as a good thing.

Neal Busch, hanger, Ridgefield Park, NJ, 1995

-- outside the chopper that was once WOR's

Neal Busch has only the best memories of being a well known voice of helicopter traffic reports in and around the New York City area. Listeners used to enjoy Neal's ability to be talking about a traffic tie-up, interrupt himself quickly and with a lower almost whisper of voice, give a message to either traffic control or another nearby aircraft, and then without losing a beat return to exactly where he was in his traffic report to the driving public.

I know Neal as a soft spoken easy friend with a great sense of humor and is so much fun to talk to. Neal is actually rather artistic and now spends his time in Florida creating sculpture and art and enjoying a very good life. He plays tennis too and believe it or not, people still turn their heads when they hear his name and sometimes just his voice. With his own hands he sculptured a duplicate head of his own which looks just like him and it's topped with the News88 logo on a helmet. The whole thing sits out on his patio floor in a kind of perpetual safe landing, can we say.

the Busch bust in helmet

When I asked him what stands out most in his mind when he thinks of flying over New York, his first response was how he loved taking his family to see, from the air, the beautiful the Christmas lights all over New York City, to circle Rockefeller Center's tree, all lit up, and watch the ice skaters there, then swing by the Statue of Liberty, before they flew home to Scarsdale to see how their own house looked with all its Christmas lights blazing.

NEAL BUSCH: JUST ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE

The uncertainty of an unexpected in-air collision

Click to READ

originally published in Flight Journal, April 2000

I just read the piece [above] and got "goose bumps" all over again recalling that night. The one thing I didn't mention in the article is that when we got to the heliport in Ridgefield Park, we put the goose, which was still very much alive in a plastic shopping bag and left it on the hangar floor. The next morning, several of us were back at the hangar looking over the damage to the helicopter, and had opened the hangar door. We next inspected the plastic bag, which had not moved from where we had placed it the night before.

As I opened the top of the bag, we nearly fell over in shock as the goose suddenly sprang to life, saw some of his friends on the Hackensack River, and flew from the heliport to the river, gracefully landing on the water like nothing had happened.

After all those years of flying, I quite often dream about flying, but haven't been at the controls for a long, long time. These days I appreciate the risks involved much more than the thrill of flight. --Neal Busch

|

1992 Teddy Bear in Neal Busch helicopter gear

commemorates Neal's 25 years of flying for WCBS

Lou Timolat is devoted to his family and is strongly drawn to nature. He's a creative builder and works with wood and natural supplies he finds in the fields of Connecticut. He has horses too and has a well respected book he authored titled November-three-three-Delta, Watch Over New York. You can talk to Lou about endless subjects and he knows something about each of them. He's an inspiration, as is Neal.

Lou and Neal both told me something I never knew they did. Do you believe they could actually smell fragrances wafting up into the air and into the helicopter from certain navigation points around the city? For example, they could smell an incinerator at 28th Street, Chinese food over China town, and an English muffin bakery at Long Island City. If they absolutely had to, they could find their bearings by nose alone.

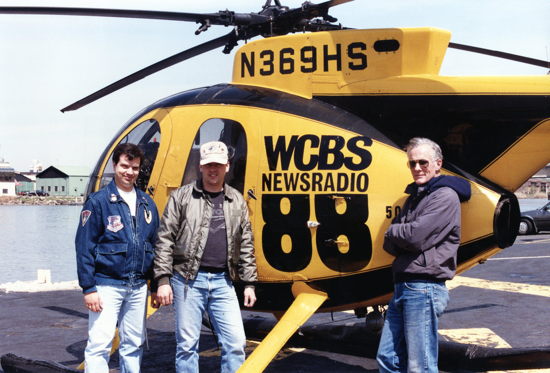

Tom Kaminski, Ed Baker (pilot/mechanic), Neal Busch

Over the years, some pretty wonderful and capable new helicopter pilots hired for traffic and news coverage over New York have proven themselves worthy of the job.

WCBS Traffic Reporter Joe Nolan, 1987

Tom Kaminski is now [February 2015] the helicopter traffic reporter for WCBS 880 and he's been happily doing this job since 1999. Tom rides in a Bell 206 Long Ranger, leased by Total Traffic, formerly known as Shadow/Metro Traffic.

Tom Kaminski

Lots of name changes over the years and the base of flight operations has also changed from Ridgefield Park to Linden Airport in Linden, New Jersey, where the WCBS helicopter is based and shared with another station for traffic and news reports. Tom's current pilot is George Lougnot. They fly together most every day and have a great working relationship. The biggest challenge aloft, according to Tom, is when all the air reporters are trying to cover the same story. "Everyone speaks on a company frequency so we make sure we're all accounted for at any given moment, but having up to 5 aircraft in a relatively tight space," Tom says, "certainly requires skill, and knowing and respecting the limits of the aircraft."

He's up there early in the morning, he knows the landscape of the greater metropolitan area in striking detail; what is usual and what is not, while safety is never out of his mind, and neither is giving the public every piece of information that will make their trip to work or to home easier. Tom makes it no secret, he loves his job, and figures it's the best job he will ever have. So he doesn't take it for granted and does right by it every single day. There is always beauty somewhere over New York, and he and George get a front row seat.

George Lougnot, Tom Kaminski

It was Tom Kaminski whose helicopter happened to be near the George Washington Bridge on the morning of September 11th, 2001. He saw the first plane hit the World Trade Center, Tower One. He reported on it immediately, at 8:48 am. When the second plane struck Tower Two they had just surveyed the damage at Tower One and were still perilously close to the continued attack. WCBS has worked extensively with the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, and just last year Tom was invited to voice a section of their audio tour that includes the devastation at Tower One and Tom's first report of the attack.

The future for Tom's work, is it changing? Tom also believes social media has opened up a new pathway, a two-way street, as he calls it. He tweets pictures from the air and listeners with traffic problems tweet inquiries directly to Tom. They may know there's a problem but Tom knows why. Tom Kaminski, he inherited the advances made by each and every news and traffic helicopter reporter who came before him, over a generation of growth and change. He caught the ball and carries it forward with honor.

DANGER IN THE AIR

On October 22, 1986, at 4:44 pm, a traffic reporter for WNBC-AM, Jane Dornacker, was killed when her chopper crashed into the Hudson River. She was thirty-nine. Her last words were "Hit the water, hit the water, hit the water!" Her pilot, Bill Pate, was badly hurt but survived. Reportedly, the crash was caused by a military surplus part, not designed for civilian aircraft, that had not been adequately lubricated, which led to a seizure of the main rotor blades.

From The New York Times of Oct. 24, 1986:

The death of Ms. Dornacker also unsettled Neil [sic] Busch, a helicopter pilot and one of the traffic reporters for radio station WCBS-AM.

''I have to talk to my other pilot and we're going to have to carefully evaluate what we're doing and ask ourselves some searching questions, like are we crazy to be up there?'' he said. ''Are we risking our lives every day up there or is the risk of this within reasonable bounds?''

Mr. Busch leases his ship and his services to the station. He flies the morning shift. Another pilot and a traffic reporter, Donna Fiducia, go up in the afternoon.

''Wednesday night, one of our reporters was live at the scene and was describing them pulling a reporter out of a helicopter,'' Mr. Busch said. ''For a few minutes, I didn't know whether it was Donna or the woman at WNBC. We're going to have to think about this. We're going to have to decide whether we are going to continue.''

Ms. Fiducia, who has been reporting from the air for about four years, used to work at WNBC. When she left the station to take her job at WCBS, Jane Dornacker took her place.

''We knew each other quite well,'' she said. ''On Wednesday, I knew she was over the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels. We often tune one another in when we're up. But I hadn't heard her for a couple of weeks.

''At any rate, I just happened to tune her in when she said she was hitting the water. I couldn't quite make out what she said. We tried to raise them. Later the word came over that she went down. We flew over the crash site to report on the traffic problems there. It was one of the most bizarre situations I've been in. It hasn't hit me yet.''

Helicopter pilots keep one eye on their instruments and another on the ground always looking for a place to make what they call ''precautionary landings.''

Distraught, Fiducia resigned from WCBS a month after the crash that killed Dornacker. A pilot for WOR, Frank McDermott, died in a crash Jan. 10, 1969, just after he went on the air to make an evening traffic report.

As far as I know, no helicopter traffic reporter in New York has died in a chopper crash since Dornacker's death in 1986. In 2013 in New York City alone, 294 people were killed in vehicular accidents, another 66,906 injured (New York State Dept. of Motor Vehicles stats). Were those on the ground to enjoy as exemplary a safety record as the broadcasters serving as our eyes in the sky. --DS

|

I can't explain why, but so many people who worked separately under the heaviest pressure at WCBS Newsradio, for years and years had private hobbies that were very similar to one another. Turned out often to be mostly photography, building or creating things, and private flying. It was quite by chance that I found this out. I never asked people at work what they did with their private time. We didn't have enough private time at work to talk about it.

But I can tell you this with certainty: Had I not worked under all the pressure at WCBS doing live programming for hours at a time, multi-tasking and forcing my brain to grow in areas of quick comprehension and accurate response, I never would have taken on some of the most rewarding challenges of my life. I actually got my pilot's license, training in Florida and soloing in 9 hours, after cross country flights and one emergency landing.

Sands

After WCBS I went on to CBS network news, then to ABC Network Television News as a reporter and traveled the country, but was invited back to News88 to be the first woman drive time anchor.

After 911, I taught a workshop at Yale University on Emergency Communications Among First Responders (including media), During an Act of Bio-terrorism. My credentials included my service as a licensed EMT in Connecticut for nearly 10 years, and an appointment to the FAA. I took it all on because I came out of WCBS News Radio a changed person.

I was a short little wispy-haired girl from Queens, NY, who was not expected to make much of herself in the world. My family did not expect a lot from such a shy girl, who lost her mother very young, and pretty much lost her home as well, as things changed so quickly. I don't know how the road led me forward, but I do know when it landed me in high-speed broadcasting, it altered everything. Only then did anything become possible. I expect that life is going to get easier now with the advent and the leadership of computers and new technologies. Everybody will begin to think in a different way.

I hope you won't underestimate the value of applying your own mind to the hardest things, even though you have a choice for "easy." The really hard work will be what teaches us as individuals; will give us power by pushing the brain to new limits. Resourcefulness will follow, by necessity. Make this the engine you never relinquish, and then fly!

Editor's note: With appreciation to John Landers, Irina Lallemand, Barry Siegfried, Bob VanDerheyden, Harvey Hauptman, Neal Busch, Tom Kaminski, Ed Salvas, and Lou Timolat who contributed to this account.

click to return to WCBS memories page

click to return to main WCBS Appreciation Site page

|