AMBROSE BIERCE AND THE DANCE OF DEATH

by David Balfour

But if there appears among you any new book, the ideas of which shock your own—supposing you have any. . . then you cry out Fire! and let all be noise, scandal, and uproar in your small corner of the earth. . . .and why? For five or six pages, about which there will no longer be a question at the end of three months. . . Let us read, and let us dance—these two amusements will never do any harm to the world. —Voltaire. A Philosophical Dictionary

IntroductionIn June 1877, the small, San Francisco publishing firm of Henry Keller & Co. issued a slender volume entitled The Dance of Death. The author was identified on the title page as “William Herman,” a name unknown to the reading public. The book is, at least ostensibly, a scathing attack on the waltz as the “the most hideous social ulcer that has yet afflicted the body corporate.” But while the primary charge made against this “abomination” is that it excited the baser passions of those who engaged in it, as illustrated in the following passage, the condemnation is itself presented in lurid terms that seemed designed to titillate:

He is stalwart, agile, mighty; she is tall, supple, lithe, and how beautiful in form and feature! Her head rests upon his shoulder, her face is upturned to his; her naked arm is almost around his neck; her swelling breast heaves tumultuously against his; face to face they whirl, his limbs interwoven with her limbs; with strong right arm about her yielding waist, he presses her to him till every curve in the contour of her lovely body thrills with the amorous contact. Her eyes look into his, but she sees nothing; the soft music fills the room, but she hears nothing; swiftly he whirls her from the floor or bends her frail body to and fro in his embrace, but she knows it not; his hot breath is upon her hair, his lips almost touch her forehead, yet she does not shrink; his eyes, gleaming with a fierce intolerable lust, gloat satyrlike over her, yet she does not quail; she is filled with a rapture divine in its intensity—she is in the maelstrom of burning desire—her spirit is with the gods.

The book brims with vivid examples of the consequences for those who indulge in the “unholy pleasures of the waltz,” including moral corruption, illicit sexual unions, broken marriages, and even murder, and its release generated a “literary sensation” in the Bay Area (“Dance of Death,” Morning Appeal), with eighteen-thousand copies sold within seven months of its appearance. Its intensely-impassioned and relentlessly-uncompromising assault on the popular waltz provoked sharply divided opinions among its readers. It received the endorsement of the Methodist Church Conference, and several professional critics and high-profile figures including Mrs. William T. Sherman, heaped praise upon it for raising public awareness about the “pernicious effects” of the waltz. Meanwhile, others ridiculed it as blue-nosed nonsense, and some debated whether the work was actually intended as satire.

The runaway success of the book also fueled considerable speculation as to the true identity of its author or authors, with several names bandied about in the press. But since the close of the nineteenth century, three individuals have been consistently identified as collaborators on the work: the relatively obscure poet and translator Thomas A. Harcourt, the prominent San Francisco photographer William Herman Rulofson, and the celebrated American writer Ambrose Bierce. At various times, each of these three men offered their own accounts of how the book came to be, which, however, differ in some important details, and questions persist as to the true purpose of the book and the relative contributions of each man to it. Furthermore, there is another significant piece of evidence that has heretofore been overlooked by later commentators, and which provides fresh perspective on these questions. For these reasons, a re-examination of the totality of the evidence related to the origins of The Dance of Death is warranted. The story that the sources reveal is, like the text of the book itself, replete with colorful characters, fiery passions, dark secrets, and sudden death.

“A Simple Matter of Business”

In late September of 1877, Thomas A. Harcourt provided the earliest, first-hand account of the book’s gestation. Motivated by the spurious claims of several individuals who had come forward to take credit for the work, he dispatched a note to the San Francisco News Letter in which he presented what he called “a brief and true history of the manner in which the book was produced.”

According to Harcourt, Rulofson had commenced work on the project a quarter of a century earlier, and in the intervening years he had elicited writings on the topic from a number of friends. Then, “some months” prior to the book’s publication, he had requested that Harcourt “write what [he] would on the matter” and put the manuscript in final form. Harcourt calls this arrangement “a simple matter of business,” but it was no doubt facilitated by the fact that, at that time, he was married to Rulfson’s oldest daughter, Fanny.

Harcourt goes on to assert that, with “one exception,” the contributions from Rulofson’s friends, which he says were in the form of letters, “had failed to catch his idea” and were, therefore, rejected. The author of the single exception was identified only as “a well-known literary gentleman not now residing in San Francisco.” Subsequently, it would be confirmed that the individual referred to here was Ambrose Bierce, a friend of Harcourt and fellow-member of the Bohemian Club who had relocated from San Francisco to San Rafael shortly before Harcourt dispatched his letter. Though the bulk of his greatest literary work lay in the future, Bierce was already well-known in the Bay Area as a journalist of caustic and deeply-cynical wit. Harcourt estimates that only about three pages of Bierce’s prose were retained in the final text of the book. “Therefore,” he concludes, “the credit, or discredit, of writing the book must be given to William H. Rulofson, and to no one else.”

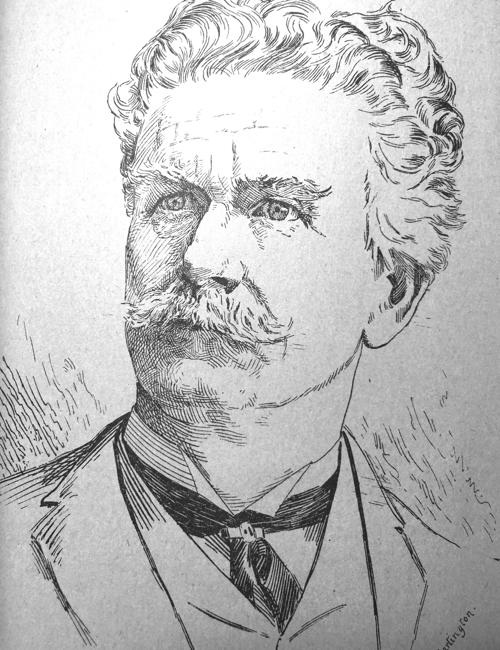

Contemporary sketch of Ambrose Bierce

by J.H.E Partington

Whether or not the notoriety of The Dance of Death might have, in the long-run, served as a much-needed boost to Harcourt’s literary and financial fortunes will never be known. For not long after his letter appeared in print, he, in the words of his erstwhile associate Bierce, “went to the everlasting bad through domestic infelicity and foreign brandy, dying in poverty’s last ditch as serenely as a king upon a golden couch (“Prattle,” San Francisco Examiner).” More prosaically, wasted by alcohol and distraught over abandonment by his wife, Harcourt took his own life by throwing himself out a window.

“I Was Never More Earnest in My Life”

Although he enjoyed much more worldly success than his son-in-law, an eerily similar fate awaited Rulofson himself. William Herman Rulofson was born in in New Brunswick, Canada in 1826, and following some early travels migrated to California in 1849. After a brief and unsuccessful stint as a gold-miner, he returned to an early interest in photography, and in 1863 became a junior partner in W.H. Bradley’s photographic studio in San Francisco. In the years that followed, he introduced many new photographic techniques and combined his inventive capacity with a flair for self-promotion that eventually led to him being dubbed “The P.T. Barnum of American Photography.” As a result, Bradley and Rulofson flourished, and Rulofson established himself as a highly-respected member of San Francisco society and a pillar of the local Episcopal Church. As will be demonstrated, however, his public persona veiled some uncomfortable truths about his private self.

In an interview conducted in late 1878, Rulofson offered his own comments on the book’s origins that generally accord with those of his son-in-law. He reaffirms Harcourt’s contention that he, Rulofson, was primarily responsible for writing The Dance of Death and heatedly rejects the notion that the work was intended as satire or designed simply to turn a profit. “I never was more earnest in my life,“ he insists, noting that as a young man he had lost a fiance to the seductive lures of the waltz. Some years after this incident, Rulofson relates, he and an unnamed Episcopal clergyman of his acquaintance had composed the first draft of the work, and for the intervening two decades he had been periodically revising the text, before finally submitting it to a publisher. He concludes the interview by declaring, “I have shown society what a loathsome ulcer festers in its midst” and promising, “I shall write another book soon showing the remedy” (“Dance,” Morning Appeal). He was, however, unable to fulfill that pledge, for within a few weeks of making it, he was dead.

“A Trinity of Moral Imposters”

A little less than a decade after Rulofson’s interview, Ambrose Bierce finally addressed the topic of The Dance of Death in his “Prattle” column in The San Francisco Examiner of 5 February 1888. Bierce’s version of events diverges from those of Harcourt and Rulofson on two key points. He contends that while Rulofson “suggested the theme and supplied the sinews of sin” for the book he “wrote none of it—he merely ‘financed’ it. My collaborator was Thomas A. Harcourt, his son-in-law.” And in contrast to Rulofson’s firm avowal of its serious intent, Bierce dismisses the book as a “monstrous joke”:

Suffice it that the purpose of the book was not moral reform, and all the commendation that it received on that ground was bestowed upon as unworthy a trinity of moral imposters as any that I ever blushed to belong to. . . under cover of an attack on prudes, [it was] as detestable a piece of cynicism as ever deserved to be burned by the public hangman.

Clearly, for Bierce at least, the entire project was a lark, and for him the fun did not end with the book’s publication. In the following months he did his best to fan the flames of controversy that it had ignited by penning several fierce denunciations of the book, such as the following from the Argonaut of 23 June 1877:

‘The Dance of Death’ is a high-handed outrage, a criminal assault upon public modesty, an indecent exposure of the author’s mind! From cover to cover it is one long sustained orgasm of a fevered imagination—a long revel of intoxicated propensities. And this is the book in which local critics find a satisfaction to their minds and hearts! This is the poisoned chalice they are gravely commending to the lips of good women and pure girls! Their asinine praises may perhaps have this good effect: William Herman may be tempted forth, to disclose his disputed identity and father his glory. Then he can be shot. (Quoted in O’Connor 113-4)

Conversely, when, in the wake of the success of The Dance of Death, there appeared a book-length defense of the waltz entitled The Dance of Life, credited to “Mrs. Dr. J. Milton Bowers,” Bierce labeled it “the most resolute, hardened, and impertinent nonsense ever diffused by a daughter of the gods divinely dull! [sic]” Though some sharp-eyed critics pointed out that “Mrs. Dr. J. Milton Bowers” was just one of many pseudonyms earlier employed by Bierce, he perversely disclaimed any responsibility for the book. Nonetheless, it is clear that, amidst the uproar fomented by the publication of The Dance of Death, Bierce was enjoying himself immensely.

The Dance of Death The Dance of Life

As appears to have been the case with his disavowal of The Dance of Life, Bierce may not have been entirely forthright in proclaiming that The Dance of Death was nothing more than an elaborate joke, for in the very same column in which he characterizes it as such, he repeatedly indicates that there was more to the book than might be apparent at first glance. For instance, at the outset he acknowledges that there are details of the story that he is not prepared to reveal:

As the only person now living who had a hand in that piece of “admirable fooling” I am tempted to relate the entire incident—or, as our current slang would more graphically express it, “give the whole business away.” Well, I will not—at least now.

A bit later, he adds cryptically,

Of the manner of the denunciation I have nothing to say in defense, further than it was adapted rather intelligently to the purpose. Of what that was there is now no record, except possibly certain private letters, some of which, I tremble to think, may be in my own handwriting.

And he concludes the article with,

Altogether, there was a good deal more in the “Dance of Death” incident than the public was invited to know, for, as one of Congreve’s characters says of woman as a good person to keep a secret, “Although I am sure to tell it, yet nobody will believe me.

Bierce may offer a clue regarding the covert purpose of the book in a private letter to writer and artist Charles Dexter Allen dated September 27, 1911. There, in contrast to his public suggestion that Rulofson was in on the joke, he discloses that, although the book was “merely an opportunity to ‘make mischief; and a ‘sensation,’” for himself and Harcourt, it “was a serious enough matter to Rulofson, who had a beautiful wife, very fond of the particular kind of dance condemned.”

This revelation raises questions about Bierce’s inclusion of Rulofson in his “trinity of moral imposters.” For if The Dance of Death was a sincere reflection of Rulofson’s feelings in regard to the waltz, then in what way does he qualify as a moral imposter? The most likely answer is that, in Rulofson’s case, Bierce was alluding to the fact that much of the photographer’s private life stood in stark contrast to his carefully-cultivated public image.

Any trouble that arose between Rulofson and his spouse over her fondness for the waltz was only one manifestation of a deeply-troubled domestic situation. Just four months after the death of his first wife in 1867, Rulofson, then forty-one, married twenty-three-year-old “renowned beauty” Mary Jane Morgan, who worked as a receptionist at Bradley & Rulofson. The marriage did nothing to improve his relations with the five children from his first marriage, already strained due to Rulofson’s violent temper and tyrannical ways. When barely in his early teens, Rulofson’s second son, Alfred, ran away to sea to escape his father’s brutality, and upon his return arranged to be adopted by the captain of the schooner on which he had sailed. And just prior to the publication of The Dance of Death, twelve-year-old Mattie, the youngest child from Rulofson’s first marriage, contracted pneumonia and died after being sent out on a cold and rainy day to run an errand for her stepmother. When her body was examined, it was found to be covered with welts, believed to have been inflicted by her nine-year-old stepbrother, Charles.

Though Rulofson usually made every effort to keep the more questionable aspects of his past and present life out of the public eye, he provided a glimpse of the volatile nature that lay beneath his respectable exterior when, in 1874, he appeared as a character witness on behalf of a Bradley and Rulofson employee, Eadweard Muybridge, who was on trial for killing his wife’s lover. Rulofson’s testimony that “a ‘crime of passion’ was only a manly act” helped to obtain Muybridge’s acquittal. On the other hand, Rulofson was particularly careful to conceal his relationship to the most infamous member of his family, his oldest brother, John Edward Howard Rulloff (1819-1871), made infamous in the press as “The Genius Killer.” Rulloff was an intellectually-gifted schoolmaster, doctor, lawyer, inventor, college professor, and multi-disciplinary scholar. But in addition to his wide-ranging intellectual interests, under various aliases he pursued a very active criminal career as an embezzler, professional thief, and serial killer, whose victims included his wife and their two-month-old daughter. He was hanged on 18 May 1871 in Ithaca New York for the murder of Frederick Merrick, whom Rulloff shot in the course of a botched robbery. Although Rulofson never publicly acknowledged his relationship to Rulloff, he secretly visited his brother in his cell in Binghamton, NY a few days before his execution.

Rulofson’s double life came to an abrupt end on November 2, 1878, when he plunged to his death from the roof of the Bradley and Rulofson studios while inspecting work on a skylight. Witnesses reported that as he was falling, he shouted, “My God, I am killed.” Curiously, following his fatal descent he was found to be carrying a small picture of his notorious eldest brother in an inside coat pocket.

Rulofson’s death was ruled accidental, but there was widespread speculation that it was actually suicide or even murder. Bierce was among those who believed that his friend had taken his own life, declaring that he “executed a ‘dance of death’ by walking off the roof of a high building” (“Prattle,“ San Francisco Examiner). Although he does not say so explicitly, Bierce evidently believed that Rulofson’s final act was motivated, in large part, by severe marital strains resulting from the publication of The Dance of Death.

“The Stormy Petrel”

As has been argued by Richard W. Bailey, Rulofson’s true personality is “vividly on display” in the over-heated prose and emotional intensity of The Dance of Death. Nonetheless, some later scholars—ignoring or at least discounting the published remarks of Rulofson and Harcourt, as well as Bierce’s own private comment to the contrary—have been apt to accept Bierce’s published declaration that Rulofson had little or nothing to do with the composition of the book, and his implication that, for all involved, the book was simply a “hoax.” Moreover, they have wholly disregarded another noteworthy and contemporary bit of evidence related to the book’s genesis.

This overlooked evidence is in the form of a letter by Olive Harper (Nancy Ellen [later Helen] Burrell d’Apery, 1842-1915) that was initially published in the San Francisco Globe-Democrat in the summer of 1881. Quite well-known at the time but almost entirely forgotten today, by the time The Dance of Death was unleashed upon the world Olive Harper had already led an eventful life. Born in Tunkhannock, Pennsylvania in 1842, in the winter of 1852 she and her family relocated to the fledgling and still wild frontier town of Oakland, California. In 1857, at the age of fourteen, she married forty-two-year-old George Gibson, who had come to Oakland with a scheme of cultivating oysters in the Bay. But, as his business ventures faltered, Gibson grew increasingly dependent on alcohol and abusive toward Harper.

She divorced him in 1871, but shortly thereafter contracted typhoid pneumonia and inflammatory rheumatism, which rendered her bedridden for a year. During this time, the cartilage in her left knee atrophied in a bent position and she was forced to walk on crutches for the remainder of her life. At the age of twenty-nine, divorced, disabled, and with three young children to support, she made the bold decision to make her way as a professional writer. Her lively and often controversial writings—frequently characterized as “spicy” by contemporary critics —garnered considerable attention, and her satirical pieces, travel writing, short fiction, and poetry were soon appearing regularly in the Daily Alta California, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and other newspapers and periodicals across America.

In the wake of this improbable success, she was sent abroad by the Alta and the Globe to cover the World Exhibition in Vienna as well as to report on the interesting places she visited in the course of her travels. While in Vienna in June 1873, she met and shortly thereafter married Telemaque d’Apery, the son of a Napoleonic officer and a Turkish subject of Greek descent, who had served as an officer in the Ottoman army and later as imperial treasurer. The couple eventually moved on to Constantinople, where, improbably, they came under suspicion of plotting against the Sultan. Harper was briefly imprisoned by the Ottoman authorities before being freed at the behest of the American consul. With her new husband, she returned to the United States, initially settling in Philadelphia, where, in 1876, she covered the Centennial Exhibition for several newspapers. By November of that year, she was in the late stages of pregnancy, and she and d’Apery travelled to the Bay Area in California where she could rest and enjoy a long-delayed reunion with the children from her first marriage.

Sketch of Olive Harper, Bancroft Library, Berkeley

In her letter to the Globe-Democrat, Harper relates how, while in the Bay Area, she received a letter from Rulofson inviting her to visit his studio and sit for a portrait.

While there he brought me the MSS in question [The Dance of Death], and as I sat waiting my turn to be photographed he read a good portion of the MSS, some of which I urged him to strike out, which he did. A clergyman of my acquaintance had added some to the book, and a lady who keeps a seminary in Oakland, also wrote a portion of a chapter, and at Mr. Rulofson’s solicitation, I also added a chapter. (“Dance of Death,” Minneapolis Journal)

An examination of The Dance of Death lends credence to the story told by Harper in this letter and calls into question Harcourt’s remark that all contributions solicited by Rulofson, save those of Bierce, were discarded. In the opening section of the sixth chapter of The Dance of Death, “William Herman” explains that among those from whom he sought input for the book was “one of the most eminent and renowned women of America. . . .a woman of unusual strength of character. . . whose intellect has gained her a worldwide celebrity and earned for her the respect and attention of multitudes wherever the English language is spoken.” While expressed in the hyperbolic fashion that typified the book as a whole, this description generally fits Harper, who was at the height of her celebrity at the time.

The remainder of the chapter consists of this woman’s first-hand account of her early dancing experiences that, in many particulars, echoes portions of Harper’s unpublished memoir, “The Stormy Petrel,” wherein she recounts how, as a young girl in Oakland, she regularly participated in “round dances.” Most tellingly, though the unnamed narrator of chapter six of The Dance of Death specifically names only five of the dances in which she participated as a girl, and Harper only six, four of these are the precisely the same in each reminiscence—the Varsovienne, the polka, the Virginia Reel, and the Money Musk.

Likewise, in regard to the attitude of the adults around her, the anonymous author recalls, “no one said to me: you do wrong. . . .we had been taught that it was right to dance; our parents did it, our friends did, and we were permitted,“ which corresponds closely to what Harper has to say on the same topic in her memoir. There, she relates that during her childhood in Oakland “social intercourse” was very limited, and, as a result “balls became the rage” and hotels in the Bay Area would host them regularly. As a standard courtesy, Harper’s father, Albert, a hotel-owner at the time, was obliged to host such entertainments as well as to attend similar functions at other hotels in the area. And since in its early days the male population of Oakland greatly outnumbered that of the women, the hotel owners were expected to bring along their wives and daughters. Young women were in particularly short supply, and therefore, “any little girls who could dance at all did dance—and all might too—some of them adopting all the airs and graces of matrons.” Harper, herself, was provided with dance lessons before she was eleven, and for a time she, along with her parents, took part in all of the dances in the area.

The primary difference between the two narratives is that while Harper, in her memoir, fails to mention the waltz by name, that dance, and the erotic impact it had on the narrator, is the main focus of attention in chapter six of The Dance of Death:

In the soft floating of the waltz I found a strange pleasure, rather difficult to intelligibly describe. The mere anticipation fluttered my pulse, and when my partner approached to claim my promised hand for the dance I felt my cheeks glow a little sometimes, and I could not look him in the eyes with the same frank gaiety as heretofore.

But the climax of my confusion was reached when, folded in his warm embrace, and giddy with the whirl, a strange, sweet thrill would shake me from head to foot, leaving me weak and almost powerless and really almost obliged to depend for support upon the arm which encircled me. If my partner failed from ignorance, lack of skill, or innocence, to arouse these, to me, most pleasurable sensations, I did not dance with him the second time.

The narrator goes on to explain that she did not, at that time, fully comprehend the pleasure she was experiencing, but as a mature woman she now felt shame “when I think of it all.” And while Harper’s memoir does not offer anything parallel to this extended description of the amatory sensations stimulated by performing the waltz, she provides a hint of growing unease over the feelings that round dancing in general aroused in her when she says that she eventually drew away from the activity because she was “nervous from. . . the changes brought about by my age.”

The differences between these two narratives are easily accounted for when several pertinent factors are considered. The first is that they were written for very different audiences and entirely different purposes. “The Stormy Petrel” was written in 1915 while Harper was on her death bed in the Philadelphia home of her youngest son, Tello. She understood that her son would be the first to examine the manuscript, and it may very well have been written predominantly for his benefit. Overall, the tone of her memoir is quite different from that of the more controversial or “spicy” journalism for which she was known, and it is understandable that she would not wish to dwell on the sort of feelings that dancing awakened in her adolescent self, and only hint at them in vague terms. By contrast, what Rulofson wanted for his book was a fiery condemnation of the waltz that emphasized the immoral passions that it stirred in its participants, and Harper, as a professional who wrote primarily to support herself and her family, was very adept at giving her patrons and readers what they wanted. In this sense, the narrative contained in chapter six of The Dance of Death strongly recalls much of Harper’s fiction, in which she would incorporate episodes from her own life, embellished for the purposes of the story.

Furthermore, any differences that are not the result of Harper’s own tailoring of each narrative, likely stem from her input to The Dance of Death being edited, perhaps heavily, before publication. Indeed, it is possible that some portions, such as the paragraphs quoted above, may have been wholly composed by Harcourt, Rulofson, or possibly Bierce, in order to enliven the narrative and better suit the tone and intention of the book. Nevertheless, even if extensively re-written, it is clear that at least some elements from Harper’s original submission remained in the published text.

Conclusion

The similarities between chapter six of The Dance of Death and parts of Olive Harper’s memoir lend considerable credibility to the claims she makes in her letter to the Globe-Democrat and critically undercut Harcourt’s statement that all the contributions to the book solicited by Rulofson, except for portions of what Bierce had written, had been ultimately set aside. It may be that what Harper, and perhaps some others, had written had already been integrated into the manuscript by the time it came into Harcourt’s hands, and it was only the extraneous letters that he refers to that were actually discarded.

Harper’s comments also lend support to the assertions of Harcourt and Rulofson that the latter was largely responsible for the composition of the book, and calls into serious question Bierce’s statement to the contrary. Looking at the evidence as a whole, it seems clear that the book may have been nothing more than an elaborate jest to Bierce, but it was a genuine reflection of Rulofson’s profound contempt for the waltz. And while Bierce, through his contradictory and amusingly-exaggerated published reactions to the book, certainly played a prominent role in escalating the controversy that it roused, his part in the actual composition of the text may have been more limited than some scholars have suggested.

Admittedly, while Harper’s letter serves to shed additional light on how The Dance of Death came to be, it does not, of course, provide definitive answers to the various questions surrounding that topic. In spite of lingering questions, however—or perhaps because of them—the twisted story of The Dance of Death, and the larger-than-life personalities involved, continue to intrigue.

Postscript: “She is Rather Vulgar”

It would be interesting to know if Bierce was aware of the modest part that Harper played in the writing of The Dance of Death, for by 1877 the two were not unknown to each other, and their earlier dealings had been less than amicable. In 1873, en route to the Vienna Exhibition, Harper was in London, sharing lodgings with fellow California writers and Bierce associates, Joaquin Miller and Charles Warren Stoddard. At the time, Bierce was also residing in London with his wealthy bride, Mary Ellen (Mollie). When Bierce refused an interview request, Harper, apparently abetted by Miller, retaliated with a biting article entitled “Snobocracy Abroad” that originally appeared in the New York Daily Graphic for 17 September. In it, she wrote:

A.G. Bierce, who used to do the “town crying” in the San Francisco News Letter, and who married a rich wife and who afterwards emigrated to London, where he has recently published a book, was simply Bierce in California; but, as soon as he felt the honored soil of England beneath his no means slender feet, he became “Major Bierce.” Joaquin Miller says the only thing that could possibly have given him reason to claim a military title was that he once used to “marshal” Irishmen around his father’s brickyard.

This item was decidedly unfair to Bierce, who had fought courageously as a Union officer in the Civil War and been promoted to the rank of Major in 1867. In November Bierce responded in an open letter to Miller that appeared in several London newspapers. In it, he appeared to exonerate Miller and place the blame for the offending article squarely on the shoulders of Harper:

Dear Miller: It would be a favor to Mrs. Harper if you would kindly intimate to her, in any way you like, that I hope she will not do me the doubtful honor of calling. Perhaps when she shall have associated long enough with the nobility and tradespeople, her manners will improve, and her conversation acquire a touch of decency; at present she is rather vulgar. I trust this will not offend you; if it does, I am very sorry. Anyhow, it is better that you should keep her from calling than to have my servant shut the door in her face. I shall be glad to see you at my lodging at any time, where you are sure of a hearty welcome.

It seems that Bierce’s animosity toward Harper persisted for a number of years, for, in The Wasp in late 1881, he attacked the “fathomless obscenity” of her verse.

Works Cited

Bailey, Richard W. Rogue Scholar: The Sinister Life and Celebrated Death of Edward H. Rullof.University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Balfour, David. “Olive Harper: A Brief Biography,“ in The Sociable Ghost and Other Curious Tales, by Olive Harper. Edited by David Balfour and Johnny Mains. Ramble House, 2022.

Bierce, Ambrose. The Complete Works. E-book, Kindle, 2013.

_____________“Prattle.” The Wasp, 2 Dec 1881, vol 7, p. 358.

_____________“Prattle.” The San Francisco Examiner, 5 Feb 1888, p. 4.

_____________ “To Charles Dexter Allen,“ 27 Sep 1911, p. 215, in A Much Misunderstood Man: Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce, edited by S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz. Ohio State University Press, 2003.

“Brevities.” Daily Alta California [San Francisco, CA], 27 December 1876.

“The Dance of Death.” Morning Appeal [Carson City, Nevada], 1 June 1881.

Fatout, Paul. Ambrose Bierce: The Devil’s Lexicographer. University of Oklahoma Press, 1951.

Grenander, Mary Elizabeth. Ambrose Bierce. Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1971.

______________________“Henrietta Stackpole and Olive Harper: Emanations of the Great Democracy,“ The Bulletin of Research in the Humanities. Vol. 83, Autumn 1980.

Haas, Robert Bartlett. “William Herman Rulofson: Pioneer Daguerreotypist and Photographic Educator (Concluded).” California Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. 34, n. 1, 1955.

“William Herman Rulofson: Pioneer Daguerreotypist and Photographic Educator.” California Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. 35, n. 1, 1956.

Harcourt, T.A. “Authorship of the Dance of Death.” San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser, 29 Sep 1877.

Harper, Olive. “The Dance of Death.” The Minneapolis Journal, 29 Aug 1881.

___________ The Stormy Petrel. Unpublished Manuscript, BANC MSS 68/41 c v.1, Bancroft Library, University of California.

____________“Three Little Gold-Diggers.” Our Little Men and Women: Illustrated Stories and Poems for Youngest Readers. D. Lothrop Company, 1893.

Herman, William. The Dance of Death. Third edition. San Francisco: Henry Keller, and Co., 1877. Google Books

McWilliams, Carey McWilliams. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. Albert and Charles Boni, 1929.

Morris, Roy Jr. Ambrose Bierce: Alone in Bad Company. Crown Publishers Inc, 1995.

N. “’Olive Harper’ in the South.” Huntsville Independent [Huntsville, Alabama], 31 May, 1877.

O’Connor, Richard. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1967.

“Pens Story of Life Then Novelist Dies.” Philadelphia Bulletin, May 4, 1915, p. 1 in The Stormy Petrel. Unpublished Manuscript, Bancroft Library, University of California.

Sherman, Ellen E. “The Dance of Death.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 12 Sep 1877.

Swaim, Don. “Ambrose Bierce Chronology.” The Ambrose Bierce Site.

Voltaire. A Philosophical Dictionary, vol. 7, translated by William F. Fleming. Paris, London, New York, Chicago: E.R. Dumont, 1901.

Wiggins, Robert A. Ambrose Bierce. University of Minnesota Press, 1964.

About the Author

David Balfour is a semi-retired historian. He first became interested in Olive Harper in 2018 when he casually selected a first edition of her novel, A Fair Californian, off the free shelf of his local library. He has since edited a new edition of that work (Ramble House 2018) as well as The Sociable Ghost and Other Curious Tales, a collection by the same author (Ramble House 2022). He is currently working on a biography of Olive Harper. Email: drfell55@gmail.com

Top of Page

|

|