Benet, Bierce & Me

the AMBROSE BIERCE site

Benet, Bierce & Me

the AMBROSE BIERCE site

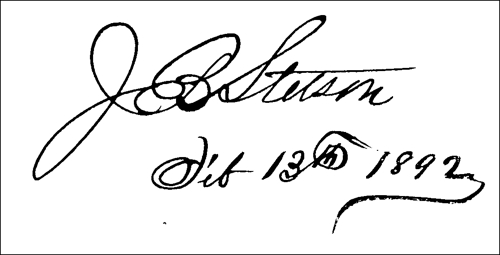

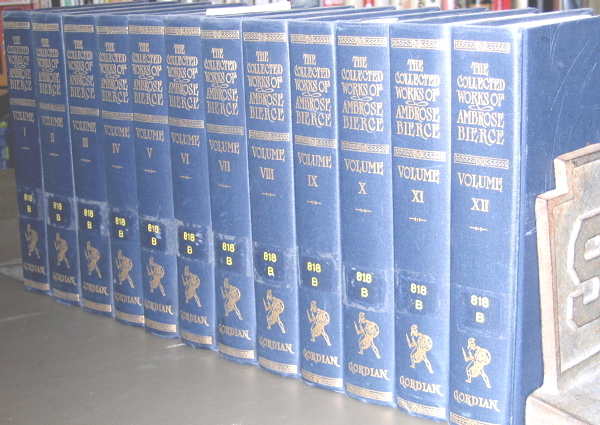

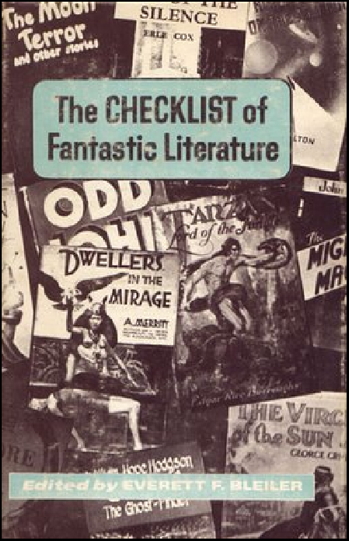

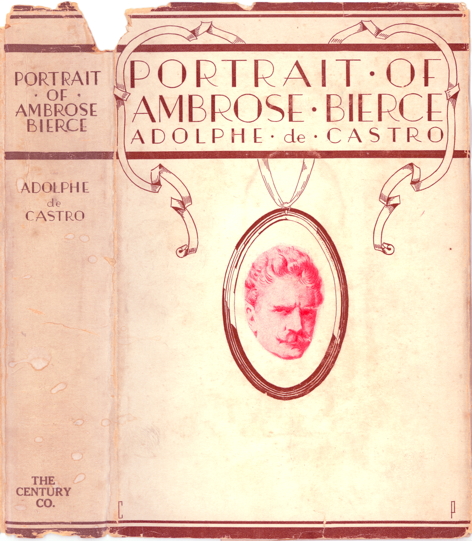

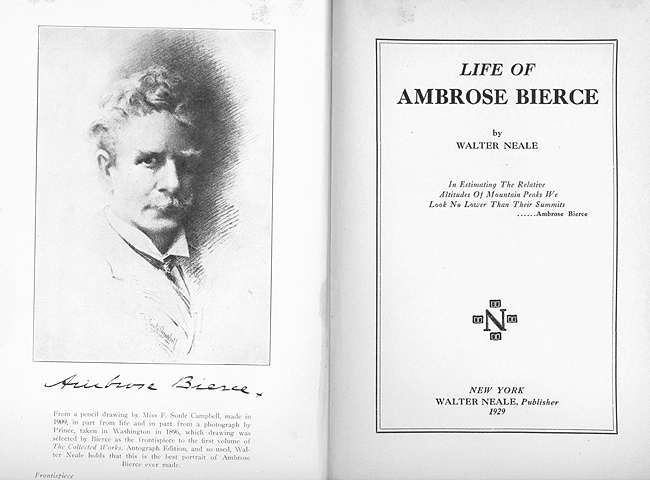

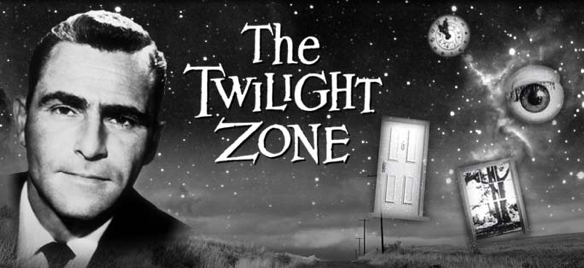

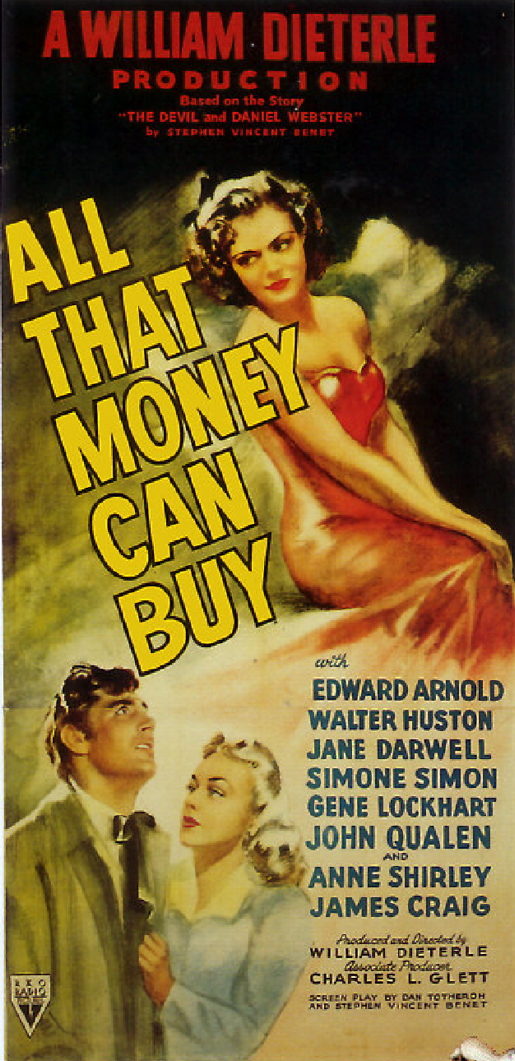

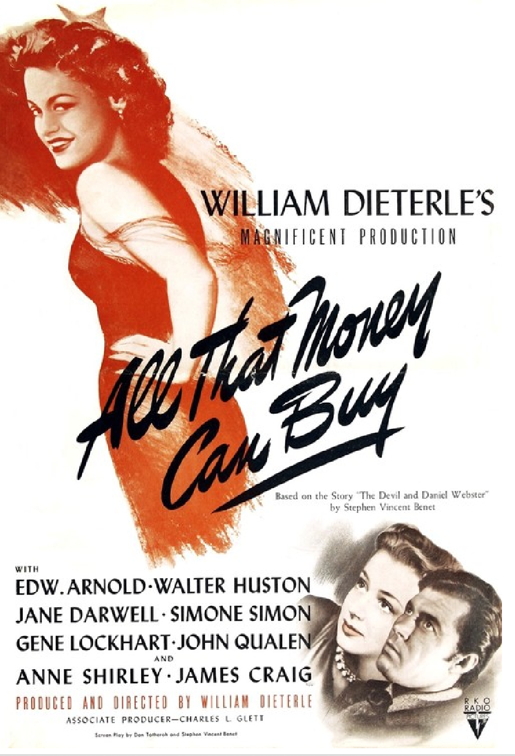

Stephen Vincent Benét, Ambrose Bierce, and Me ___________________ Bierce who? Benét who? The names may be vaguely familiar to some readers. If not, simply stated, the two were authors—accomplished in the true authorial sense. But fabulists? (Fabulist. n. A person who composes or relates fables. A person who invents elaborate, dishonest stories.) The answer’s affirmative in many ways. I discovered both in my teens, and they’ve been among my literary companions ever since. This essay started out as a kind of scholarly and academic enterprise. Then I realized I was neither scholarly nor academic. So it veered off into a more personal direction (thus the subtitle), which instantly disqualifies it from any sort of pedagogical entity. What links the two authors, no matter how tenuously, is the fact that both were consummate men of letters whose fantasy and supernatural stories left an indelible mark on America’s literary narrative. That’s not, however, to negate their magnificent contributions to the nation’s Civil War saga. As the older of the two, Ambrose Bierce would not have been aware of Stephen Vincent Benét, whose first book, a subsidized collection of poems called Five Men and Pompey, was published in 1915, a year after Bierce’s disappearance.  Benét’s first book in original tan dust jacket. Published in 1915 while at Yale. And nowhere in his writing does the younger Benét cite Bierce. However, Benét’s horror story “The King of the Cats,” evokes such Biercian tales as “The Eyes of the Panther,” and Bierce’s yarn of a robotic chess-player gone murderously mad, “Moxon’s Master,” is no less of the science-fiction genre than Benét’s doomsdale tale “By the Waters of Babylon.” Aside from their supernatural stories, both men wrote eloquently of the Civil War, Bierce in his many tales of valor and disgrace, and Benét in his epic poem, John Brown’s Body, with both real and imagined images of the nation's terrible conflict, the half-crazed Brown being only a part of it. Several of Bierce’s stories, notably “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” have been filmed, as have Benét’s, such as “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” (foolishly retitled All That Money Can Buy) and “The Sobbin’ Women,” basis for the musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.  Based on Benét’s story Benét wrote the librettos for operatic versions of two of his works, one of which was The Headless Horseman, based on Washington Irving’s Ichabod Crane fable. At least four of Bierce’s stories have metamorphosed into operas. The two writers couldn’t have been more unalike—even ignoring the vast difference in their ages: fifty-six years. Bierce died, presumably in his early seventies (the exact date of his death is unknown), a respectable lifetime for a man born in 1842, particularly one suffering from a lifetime of asthma. Benét, with chronic ill health, including arthritis of the spine and the effects of childhood scarlet fever, was born in 1898. After he died of a heart attack in 1943, Benét’s widow Rosemary said that despite his uncertain health, her husband’s sudden death was “as unexpected as a bolt of lightning.” In addition to his excruciating asthmatic pain—he slept on a board and wore a corset—Benét in 1939 was hospitalized for several weeks after suffering a nervous breakdown, but little is publicly known about this episode in his life. Benét was forty-four at the time of his death, the same age as F. Scott Fitzgerald when he died, also of a heart attack. While Benét was writing his first novel, The Beginning of Wisdom, published in 1921, he was all too aware of Fitzgerald’s celebrated 1920 debut, This Side of Paradise. Benét told a Yale classmate that he had a lot of fun writing his college stuff, although it’s “less gaudy and Sophomore Don Juan than F. Scott Fitz,” and that his “three drunk scenes were a sheer pleasure to do.”  Benet’s first novel, 1921 *** Benét’s literary fate has been to be nearly ignored. Bierce fared luckier. Virtually all of his supernatural and Civil War stories remain in print in any number of collections and anthologies, as well as on the Internet—and growing. Some of his best known weird tales include “The Damned Thing,” “The Death of Halpin Frayser,” “The Moonlit Road,” “The Haunted Valley,” and “A Watcher by the Dead.” Those are just a few of his short works, which were republished by the University of Tennessee Press in three volumes in 2006. Bierce’s Civil War masterpiece “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” (described by Kurt Vonnegut as “...a flawless example of American genius.”) might be considered more psychological horror than supernatural. An accused spy is about to be hanged from a railroad bridge by Union soldiers. As he plummets from the end of the rope, he senses that the line has snapped. He plunges into the stream and escapes to the ultimate sanctuary of his wife and child. But—here’s the shocker—the rope hasn’t snapped. Delicious.  Still photo from Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, 1964, Robert Enrico, director Johnny Depp's short film version of “Owl Creek,” with the band Babybird here “Owl Creek” set the standard for many of the psychological dramas to follow it. The story’s in Bierce’s most celebrated book, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians, published in San Francisco in 1891 by a benefactor, E.L.G. Steele (republished in England under the lame title In the Midst of Life, which, by the way, Bierce clung to for subsequent editions). I own an original copy of Tales, which I came upon serendipitously. It bears the ornate ownership signature of J.B. Stetson (of John B. Stetson hat fame) dated February 13,1892. Mr. Stetson had taste, and not only in hats.  John B. Stetson’s signature on what was once his copy of Tales of Soldiers and Civilians. In the Bierce tradition of psychological suspense, Benét’s “Elementals,” his first published short story, appeared in the April 1922 edition of Cosmopolitan (for which Bierce once wrote a column, “The Passing Show”). This dark tale is about a young couple who agree to a $10,000 wager with a stranger, a test to prove their devotion and to show that love triumphs over self-preservation. But they find themselves subjected to a diabolical nightmare the odds of which are ruthlessly stacked against them. “Elementals” was recreated as a superb CBS radio broadcast of “Escape” on October 11, 1952. Benét has been sadly neglected. To find his long out-of-print books means haunting second-hand book stores, as well as remote corners of the Internet even for some of his better known tales. Many of his supernatural stories were published in the collections Thirteen O’Clock, Tales Before Midnight, and the posthumous The Last Circle—all out of print. If a vintage copy of his more available two-volume Selected Works can be found, his chilling supernatural and prophetic verse, some of which appeared in The New Yorker, are under the heading “Nightmares and Visitants.” Lots of luck in locating these tales.

Although Benét was a connsumate literary figure, I suspect that after his death he was marginalized because he wrote for the lucrative popular magazine market such as The Saturday Evening Post and Colliers. An author who is well paid by big circulation publications and is popular with the general public is often destined for academic purgatory. But it shouldn’t be forgotten that Benét, who also wrote for radio, earned two Pulitzer prizes for his poetry, John Brown’s Body and Western Star, the latter awarded posthumously. Several of his short stories won O. Henry Memorial Prizes. He was a Guggenheim Fellow, general editor of the annual Yale Series of Young Poets (James Agee’s editor), an editor of the distinguished Rivers of America series, and a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters (to which he was elected at the age of thirty-one). Like Benét, Bierce also penned poetry, but mostly clever, ephemeral doggerel, such as in his Black Beetles in Amber and Shapes of Clay. Two examples of his devastating epitaphs of the living: Here the remains of Schuyler Colfax* lie;* vice-president under U.S. Grant ** Collis P. Huntington, co-founder, Central Pacific Railroad While he never won a literary prize, Bierce attracted a coterie of acolytes and became California’s de facto literary arbiter. He was recognized to readers of his day as the star columnist in William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner, New York Journal, and Cosmopolitan magazine. To the end, Bierce had a love-hate relationship with Hearst, who put Bierce to work when his prospects were low—and paid him well. Bierce never forgave him.  The youthful Hearst (...“the youngest man I had ever confronted...” —Bierce) For better or worse, Bierce’s notoriety accelerated after his mysterious disappearance in Mexico, and he may be better known now than he was in his heyday. Additionally, Bierce has been the subject of several volumes of critical analysis and biography (the most recent in 1999), while the only biography of Benét is that of Charles A. Fenton’s in 1958 in addition to a single volume of critical essays. Bierce has also been mythologized in a series of mystery novels by Oakley Hall and in the novel The Old Gringo by Carlos Fuentes. In the film version of the Fuentes novel, Gregory Peck plays a credible Bierce and Jane Fonda the love interest. Bierce's legacy is manifested in its own website, which Benét lacks. *** Benét was fragile, his demeanor benign, and while he passed his Army physical in World War One by memorizing the eye chart, his rotten vision was soon detected and he was discharged after three days. Stephen (whose ancestral origins were Majorcan Spanish, not French) was born into a military family. His father was a career officer in the United States Army, and his grandfather and namesake was a brigadier general and Chief of United States Army Ordnance. Bierce too would have made a career in the military had his commission come through following the Civil War, but it did not—to the ultimate relief of his legion of readers, including myself. Born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Benét attended private schools, earned two degrees from Yale, and studied at the Sorbonne. The rural Meigs County, Ohio-born Bierce, with just one year of military school in Kentucky after high school, was a dedicated autodidact who thrived on his independent study, and if he felt that he had any scholarly limitations he never displayed them. It wouldn't have been his way.

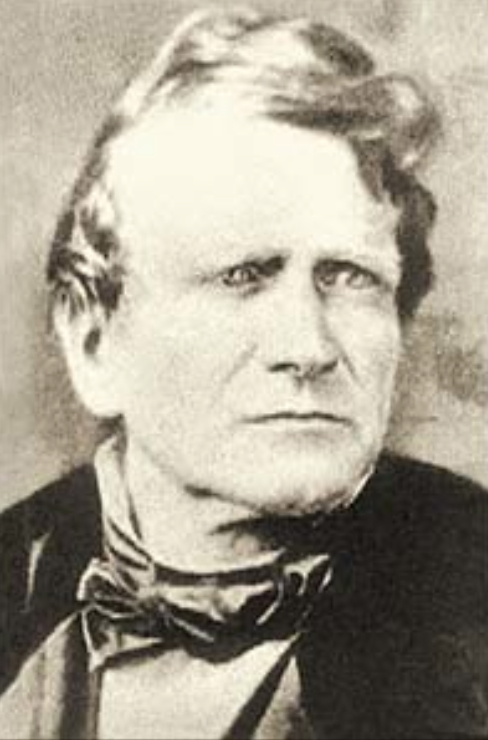

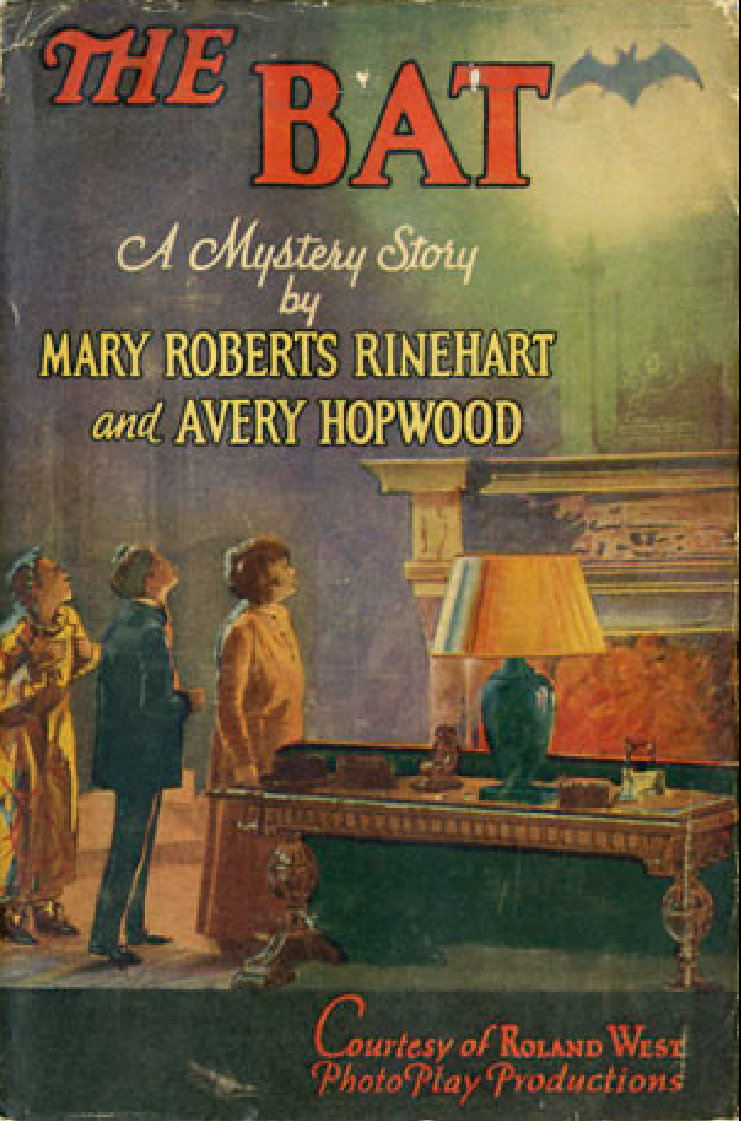

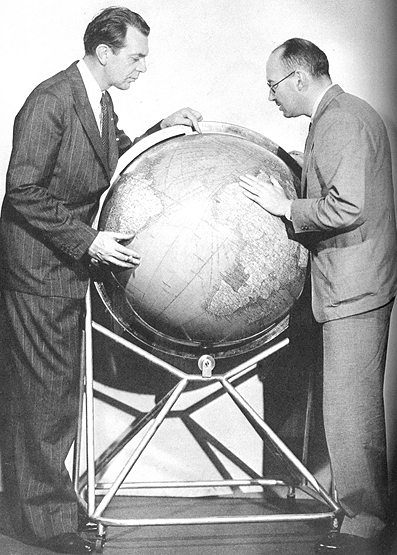

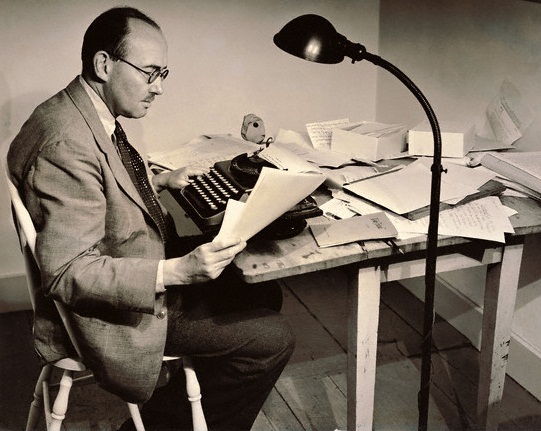

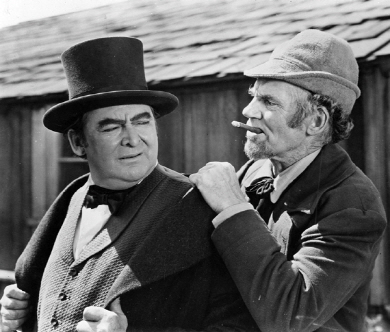

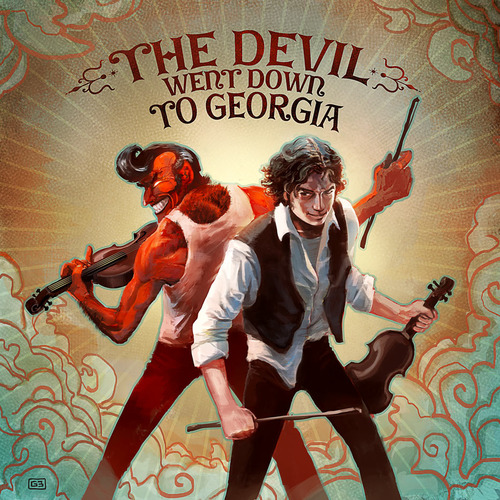

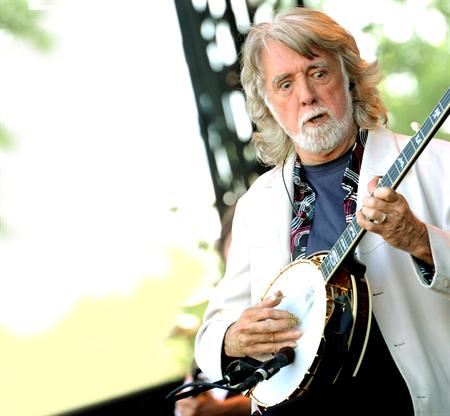

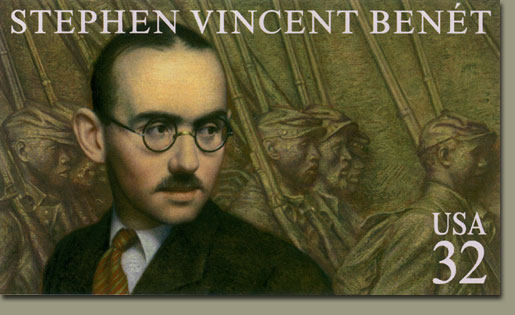

Bierce was a six-foot, caustic, hard-driving man’s man, a scalp-wounded Civil War hero, and a topographer for General William Hazen in a dangerous expedition through Indian territory. He was inspired by his strong-willed uncle, Lucius Verus Bierce, a six-term mayor of Akron, Ohio, who in 1838 led an inadequate invasion force into Canada in a futile attempt to liberate its unfortunate natives from the yoke of British oppression. Uncle Lucius’ unsanctioned folly failed, and he was sent packing back across the border leaving wanted posters in his wake. Lucius had no regrets, however, and it’s clear Ambrose took more after his colorful uncle than his drab, religious father. Benét, in his radio play “The Undefended Border,” (NBC’s “Cavalcade of America,” December 18, 1940), about the peaceful parallel between the two nations, makes no mention of Uncle Lucius’ reckless incursion.  Uncle Lucius Verus Bierce 1801-1876 In appearance, Bierce was tall and strikingly handsome. As often noted, the camera was kind to him. On the other hand, Benét’s future wife, Rosemary Carr, described her husband-to-be, with his thinning hair and feeble mustache, as “queer looking ” and “unattractive.” Nevertheless, Rosemary, an author in her own right, fell in love with Stephen, and they brought three children into the world—as did Bierce and his wife Molly, whose union ended in acrimony, a long separation, and divorce. Bierce’s domestic life was far more turbulent than Benét’s, and both of Bierce’s sons died prematurely, one in a murder-suicide, the other of pneumonia following an alcoholic binge. Benét’s older brother by twelve years, William Rose Benét, was also a dedicated literary man (his second wife was the poet Elinor Wylie). William was a founder and editor of The Saturday Review of Literature as well as a Pulitzer Prize winner for his 1941 book of poems, The Dust Which is God. He was occasionally in hock and sometimes needed his younger brother to bail him out, which was not always possible. On September 14, 1932, Stephen writes to William: “...I’ve only sold one story in the last four months. Lord knows, if I had the cash, you should have it too—and it seems perfectly ridiculous that I shouldn’t—but we are strapped.” Benét’s creative impulses ranged wide, and in 1925 he adapted as a novel the Broadway melodrama The Bat, written by Mary Roberts—“the butler did it”—Rinehart, mother of Stanley Rinehart, Benét’s publisher. As a writing job for hire, Benét’s name appears nowhere on the book. Biographer Charles A. Fenton says the fact that Benét wrote it suggests the extremes to which literary recession had pushed him.  Bat image on upper right of dust jacket. Inspiration for the Batman comics? *** Long ago, during my Pennsylvania high school years, Stephen Vincent Benét was still being read generally—although even then his popularity had waned. While contemporary American literature was taught at my high school, including the class of my revered English teacher, Mary Ida Burnite, Benét was not on the curriculum. However, on my graduation, Miss Burnite presented me a copy of Benét’s book of poems, Burning City (1936), sans dust jacket. In an enclosed note, she writes: I haven’t inscribed this, but I will if you wish. As I was trying to decide whether to get this (as I know you have copies of many of the poems), the man at Walleck’s [a local Pittsburgh bookshop] put things in a new light. ‘But,’ he reproved me as I questioned the price, ‘it’s a FIRST EDITION.’The man at Walleck’s was wrong. It wasn’t a first edition. It lacked the requisite Farrar and Rinehart colophon on the copyright page. Nevertheless, the book with its personal inscription is no less valuable to me.  In a way, I taught myself Benét—through a ratty, second-hand, mass-market paperback (with a kangaroo logo) that had been published in 1946 well before my high school years: The Stephen Vincent Benét Pocket Book edited by Robert Van Gelder. Its covers were coated with an odd, thin laminate—either to make the small book more sturdy or to waterproof it—that peeled like the thinnest skin of an onion. Every book listed a huge number on the upper right, which presumably was the number of each one printed. Who knows? The publisher probably had the notion it was good idea at the time. That cherished paperback has long faded away, although copies are still lurking within the innards of the Internet. But unfaded is my memory of Benét’s words, the most interesting of which, to my adolescent mind, were his fantasy stories and nightmare poems, precursors to my not-unusual youthful mania for science-fiction.  This 1946 paperback was my introduction to Benét. *** Benét’s passionate writing begged to be read aloud, fittingly, as he scripted many radio plays as World War Two approached, one of which was “Listen to the People,” written for Independence Day, 1941, broadcast on NBC’s Blue Network (NBC then owned two radio networks, Red and Blue, until the network was broken up by the FCC and the Blue morphed into ABC in 1945). Benét’s six-part NBC series “Letters to Hitler” was terrific, maybe overwrought, although in retrospect perhaps not wrought enough when one thinks of the appalling destruction and wanton murder for which an unhinged Germany was solely accountable. Long after the war, a Jewish friend, whose family was slaughtered by the Germans, eagerly went to Berlin to study as a Fulbright scholar. Some forgive more easily than I. In light of the Nazi specter, Benét’s poetic prediction of the future, “Nightmare at Noon,” published in 1940, anticipates how an arguably peaceful nation like America might suffer Europe’s fate. Benét concludes with this vision of doom: The bell has rung in the night and the air quakes with it.Benét’s dystopian poem “Nightmare for Future Reference” was published in The New Yorker in 1938 and narrated on the radio by Basil Rathbone (celebrated as Sherlock Holmes). Benét wrote his agent Carl Brandt that the poem would be right for a movie, “though a fantastic and horrifying one.” In it, eighteen years after the end of the Third World War—“The one between Us and Them”—a father explains the heartbreaking facts of life to his nearly grown son, concluding with this chilling revelation: And we keep the toys in the stores, and the colored books,While Benét’s poem never made it to the screen, P.D. James tackled the same haunting theme in her 1992 sci-fi novel Children of Man, which was filmed with Julianne Moore and Clive Owen. Childbirth was in the past. In “William Riley and the Fates,” Benét writes of an early twentieth century small-town picnic in which the celebrants, the United Sons and Daughters of Destiny, ponder an unfolding future with unfamiliar references, such as Sarajevo and Schicklgruber (of the Adolph Schicklgrubers) and insulin. A young reporter, who later forgets all he saw and heard, watches the events unfold on a strange silver screen: It went on, year after year, with the tumult and the confusion, the waste and the striving and the hope.... He saw men stand up against tyranny, he saw men stretch out their hands to help other men. He saw the discoveries and the inventions—he saw things that touched his heart like music. But the future’s a hard load to bear for any sort of man.A decade before Ray Bradbury published his quintessential dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, in which firemen of the future burn books instead of dousing fires, Benét wrote a savage indictment of fascism in his radio play “They Burned the Books,” broadcast on NBC on May 11, 1942. Benét’s drama dealt with the Nazi storm troopers who in 1933 torched books in order to crush nonconformist thought. The unnamed narrator in Benét’s play, citing Milton and Whitman, Tennyson and Swift, Twain and Hugo, says: These are our voices. These shall light our fire.A precursor of Ray Bradbury in 1953? I think so.  NBC publicity photo, 1930s. Benét (right) with actor Raymond Massey who appeared on several of Benét’s radio broadcasts. Recently, I listened to a recording of a dramatization of Benét’s “Nightmare Number Three,” retitled “Nightmare,” in which the machines, from cars and busses to printing presses and typewriters to elevators and telephones revolt against their human owners. The show was first broadcast on NBC’s “Dimension X” on June 10, 1951, and rebroadcast on “X-Minus One” on July 21, 1955. Even lacking today's compuer technology, the show still holds up. I recall reading Nightmare Number Three,” as well as “Metropolitan Nightmare,” aloud in the self-absorbed privacy of my adolescent sanctuary. They were wonderfully terrifying poems that I wanted to share, although I had no one to share them with—and mine was not a family of readers outside of the Reader’s Digest and the Wall Street Journal. In time, imagining myself a professional broadcaster, I recorded Benét’s poems onto a portable Revere reel-to-reel tape machine, a gift from my parents. Like The Stephen Vincent Benét Pocket Book, the tapes and the Revere, technological relics, are long vanished. Never having heard Benét’s original broadcasts, I tracked down a few preserved on the Internet—although transcripts were published in We Stand United and Other Radio Scripts, 1945. *** My early relationship with Bierce was unlike that with Benét. Some of Bierce’s short work, such as his masterpiece “Owl Creek,” had been widely anthologized, and somewhere I read his “Devil’s Dictionary,” many entries of which were amusing, but others well over my youthful capacity. It wasn’t until I was an adult, intrigued by his weird disappearing act in Mexico in 1914, that I solidly latched onto anything of Bierce I could find, culminating with my acquisition of his twelve-volume Collected Works, which I bought at a pre-library sale in New York City. I’d been visiting the Midtown Manhattan library branch on Fifth Avenue weekly to delve through the Collected Works—only one day to find them gone. Angrily, I confronted the librarian. I’d expected a hatchet-face harridan, but she was attractive and smiling, obviously accustomed to dealing with unwashed vagrants, the ignorant, lost souls, and cranks like me. She wore a library nametag reading “Miss Joseph.” Our conversation went like this: “Where are they?” I demanded.Miss Joseph was right. No one wanted them. But she was also wrong. People were still reading Bierce—although perhaps not, like me, all of the minutiae in his Collected Works. So I scored the books for seventy-five bucks, complete with their ugly library stamps and markings (rendering them useless as collectibles), and trundled them home in two laden shopping bags on the C train to Ninety-sixth Street. An unattractive addition to my cramped home library on Columbus Avenue, but what a wealth of Bierceana within.  Bierce Collected Works from New York Public Library sale Then late one night, a squad of helmeted cops bulldozed their way into my apartment looking for noise or drugs, I forget which. In a drunken haze, I proudly showed one of the ossifers my shelf of Bierce’s Collected Works. The cop said, examining the markings, “Say, them’s library books. You gotta have stolen ’em. Sarge, Sarge? Over here on the double. We got ourselves a perp.” “No, no,” I pleaded. “Look inside. It says ‘Withdrawn—may be sold for the benefit of the New York Public Library.’” Okay. Maybe I exaggerated about the cop invasion. After all, I gleaned something about storytelling from Bierce and Benét. *** While much of this discourse deals with Benét, I should cite a prime Bierce nemesis named Everett Franklin Bleiler (1920-2010), an influential voice in the literature of fantasy and science fiction whose 1948 The Checklist of Fantastic Literature is said to be the foundation of modern sci-fi lit. If Bierce had been around at the same time as Bleiler, Bierce would have shot the bastard.  Bleiler did Bierce no favors in a slanderous introduction to the 1964 Dover Books publication of Bierce’s Ghost and Horror Stories. He describes Bierce as “pathetic” and “hateable.” And that Bierce: ...was a drunkard who used to boast of the men he had drunk under the table; he suffered delirium tremens at least once. He was a hypocrite; he worked himself into paroxysms of righteous anger at the morals of others, yet lived with a succession of mistresses and left (it seems rather certain) illegitimate children.So Bleiler was “rather certain"? Really? Rather certain? Bleiler’s rambling invective (all second-hand and mostly false) is based on deficient evidence from the rantings of Bierce’s former friend Adolphe de Castro (the two had had a falling out), whom even Bleiler concedes was “a swindler, sharper, and liar...”  Adolphe de Castro’s “portrait” of Bierce, 1929 Bleiler also apparently relies on claims by Bierce’s publisher, Walter Neale, who met the author late in his life. In his unreliable memoir, the star-struck Neale devotes an entire chapter to Bierce’s sex life, which is unrevealing due to its lack of facts, and which is punctuated by such sexually suggestive absurdities that Bierce was attracted to a teenaged girl who was born deaf, dumb, blind, and a helpless cripple—yet the girl wrote poetry and prose of rare charm and beauty. Oh, spare us. At least Helen Keller could walk and talk. Can Neale be taken seriously? The answer’s obvious. But not to Bleiler.  Walter Neale's alleged memoir, 1929 Bleiler’s on firmer ground in analyzing Bierce’s supernatural tales, about which Bleiler says, “One of the most characteristic, most curious aspects of Bierce’s supernatural fiction is its very heavy use of irony, which sometimes appears in the most unexpected ways, injected as a note of sardonic, ghoulish humor into a situation of horror.” Writes Bleiler: These are the supernatural stories of Ambrose Bierce—a strange mixture of sincerity and contrivance, remarkable insights and astonishing stupidities, dazzling technique and leaden crudities, high-mindedness that often turns out to be simply vulgarity and coarseness in a bright uniform—all enacted in a strange bloody-skied land where cruelty and laughter are alternate doors to the same house of life.I might accept some of Bleiler’s pungent but snarky literary analysis, but his personal vituperation of Bierce is uncalled for and exaggerated due to Bleiler’s own fevered imagination. Bleiler conceptualized the man Bierce and simply didn’t like the SOB. I suspect Bierce wouldn’t like Bleiler much either. *** In a chapter in the 2002 Stephen Vincent Benét: Essays on His Life and Work (the only critical study of Benét I know of), Toby Johnson writes of a subgenre of science fiction in which spiritual and metaphysical issues are best manifested in a phrase coined by Rod Serling for 1950s television: “The Twilight Zone.” According to Johnson, “Stephen Vincent Benét preceded Rod Serling by some twenty years, but one can clearly find in his work precursors of the Twilight Zone.” Maybe. But the same could be said about loads of other weird fiction totally unrelated to Benét. Still, there are some examples that might play well into Serling’s fantasy world.  With its echoes of Poe and Bierce, Benét’s “The King of the Cats,” tells of an elegant French musician who conquers New York by conducting a celebrated orchestral performance—with his feline tail. The afforementioned Toby Johnson concludes that “while the story’s wisdom is light, there is a cute message about cat psychology—and its implications for human psychology...” Cute cat psychology? I have absolutely no idea what Mr. Johnson is attempting to say, but whatever it is Benét says it better. “The King of the Cats” is included in the Library of America's two-century restrospective of American Fantastic Tales, edited by Peter Straub. (Bierce is included for his “The Moonlit Road.”) In 1936, Benét mailed a short story, “The Minister’s Books,” to his agent Carl Brandt, saying it would give him “a slight shiver,” but that “I’ve always wanted to write a ghost-story...” It eventually appeared in the August 1942 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. A young minister, new to his Pennsylvania congregation, is haunted by a library of old books about sorcery and witchcraft, and, obsessed, moves to murder a drunken old man as a sacrifice. “Between good and evil there was a deep gulf fixed; there was a fearsome joy in crossing to the other side.” The library had once been owned by a man who, before he disappeared, asserted “that his soul lay in his books, and woe to them that meddled with it...” “The Gold Dress,” is an unapologetic ghost story in which a stubborn young woman’s spirit returns to haunt her fiancé who is about to become engaged to another woman. All it takes to make the ghost go away is, yes, her unworn gold dress. Benét’s tale “Doc Mellhorn and the Pearly Gates,” first published in The Saturday Evening Post, is not technically a ghost story since ghosts, as we imagine them, usually have some interaction with the living. When country doctor Mellhorn dies, he finds himself driving on the road to answer a house call from Paisley, a man known to have been dead for twenty years. After Mellhorn arrives at the Pearly Gates, he discovers that Paisley has been sent to the other place, so Mellhorn goes there because, “I’m a physician. A patient’s called.” In “The Land Where There is No Death,” a young man sets out on a tireless odyssey to find a rumored place of perpetual life, only to discover that such a realm is not on earth but in heaven. A dull businessman’s own shadow attempts to control his life in “The Dangers of Shadows.” As the man is poised to use purloined funds to abandon his job and family, he observes the weary but loving face of his wife, and ultimately defies the meddling shadow.  Benét at a rather makeshift desk *** By the middle of 1935, Benét, who lost most of his earnings in the crash of 1929, was so broke he had to borrow $250 from his agent Brandt. Depressed by his circumstances, Benét managed to complete a short story on July 9 and send it off to Brandt, who replied “It’s a honey.” Indeed. “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” Benét’s best known tale, appeared in The Saturday Evening Post of October 24, 1936. S.T. Joshi, in his Icons of Horror and the Supernatural, 2007, describes it as, “probably the most famous of all twentieth-century deal-with-the-Devil stories.” It brought Benét immediate financial relief. Biographer Charles A. Fenton says The Saturday Evening Post awarded Benét a contract for four pieces a year at $1,750 each (decent change in those years). The story was issued as a hard-cover book that went through eleven printings over the next twenty years, plus a number of deluxe editions with extravagant illustrations. It also won the O. Henry Memorial Award as the best American short story of 1936, not to mention being adapted as an operetta, a one-act play, a motion picture, and a film score.  issue featuring Benét’s Devil and Daniel Webster, Norman Rockwell cover “The Devil and Daniel Webster” is Benét’s take on the Faust legend in which hard-luck New England farmer Jabez Stone sells his soul to the devil, Mr. Scratch, in exchange for seven years of prosperity. When Scratch comes to collect, Stone begs the celebrated lawyer Daniel Webster to plead his case before a jury of the damned. Webster challenges the American citizenship of Mr. Scratch, and the devil replies: “And who with better right?” said the stranger, with one of his terrible smiles. “When the first wrong was done to the first Indian, I was there. When the first slaver put out for the Congo, I stood on her deck. Am I not in your books and stories and beliefs, from the first settlements on? Am I not spoken of, still, in every church in New England? ’Tis true the North claims me for a Southerner and the South for a Northerner, but I am neither. I am merely an honest American like yourself—and of the best descent—for, to tell the truth, Mr. Webster, though I don’t like to boast of it, my name is older in this country than yours.”Despite the odds, Webster defeats the devil in an impassioned delivery before the jury. Director William Dieterles’ film casting of “The Devil and Daniel Webster” was scrumptious. Edward Arnold plays Webster and Walter Huston is Scratch.  Walter Huston  Edward Arnold, Walter Huston In a letter to Dieterle in 1941, Benét reasonably protests the director’s decision to change the name of the film to All That Money Can Buy. Benét writes, “It isn’t just personal feeling on my part—I simply cannot see from a business point of view, throwing away the publicity value of a well-known title.” But the filmmakers, in their wisdom, wanted to avoid confusion with another RKO flick, The Devil and Miss Jones. Over time, however, All That Money Can Buy was re-released under the titles Mr. Scratch, Daniel and the Devil, and Here is a Man—none satisfactory or even close to Benét’s superior original title.   Note the lurid, misleading nature of these movie posters for the film of Benét’s Daniel Webster story Bernard Herrmann’s beguiling original soundtrack for the film brings to mind Aaron Copland’s genius. Five segments of the Herrmann score survive commercially, amounting to about twenty minutes. Herrmann (who also composed the music for Citizen Kane, Psycho and other Hitchcock films, as well as Rod Serling’s “Twilight Zone") might have been considered an illustrious classical composer had he not written for the popular culture. I’m no expert on music, but no one has given me a satisfactory explanation as to why some movie scores, including those of Bernard Herrmann, fail to rank with the best of classical music. Even Prokofiev and Copland wrote for the movies. There have been at least two musical adaptations of Benét’s folk poem “The Mountain Whippoorwill,” which was in his 1925 book Tiger Joy. In it, a young Georgia hillbilly enters a fiddlers’ contest, but his competition seems to be unbeatable until the kid begins to saw: Sing on the mountains, little whippoorwillCharlie Daniels’ 1979 exuberant rendition, under the title “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” (it was in the John Travolta movie Urban Cowboy), was a hit—but in the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s 1974 Stars & Stripes Forever album, John McEuen’s version is faithful to the original poem, and, oddly, McEuen’s bravado performance contains no fiddle, only his solo banjo. McEuen gives full credit to Benét, while Daniels claims he only vaguely remembers the poem from high school.   McEuen Benét had soured on Hollywood long before the filming of “The Devil and Daniel Webster.” In 1929, he had been hired to write a screenplay, Abraham Lincoln, for director D. W. Griffith, which proved to be a miserable experience. Benét writes to Rosemary about the Griffith’s film: “My script is full of things like ‘Camera trucks, shooting from reverse angle.’ They sound fine, but I don’t know what any of them mean.” But on the bright side: “It will be $3000 in the bank next week. Every now and then I look at that bank book—and at my return ticket.” To his agent Brandt, Benét writes, “I don’t know which makes me vomit worst—the horned toads from the cloak and suit trade, the shanty Irish, or the gentlemen who talk of Screen Art.” And again to Rosemary, after having labored over five screenplay versions of Abraham Lincoln, “It vexes me to see ignorance and stupidity and arrogance and time and talent wasted.” *** Benét’s well known post-apocalyptic story “By the Waters of Babylon” first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1937 as “The Place of the Gods,” and in book form in Thirteen O’Clock.  First appearance in The Saturday Evening Post with original title Following the “Great Burning,” the narrator, a son of a priest, sets out to find the fabled Place of the Gods, and makes his way through a dangerous man-caused wasteland to the cliffs overlooking a great river, which he crosses on a raft. He enters the ruins of what was once an enormous city now populated only by wild dogs and pigeons. The horror grows for the reader when it becomes apparent that the ruins were once the city of New York. The young man makes a startling discovery in finding the mummified remains of a man, and determines that the long-dead gods he had sought had been mere mortals, such as the dead man in the chair. He had sat at his window, watching his city die—then he himself had died. But it is better to lose one’s life than one’s spirit—and you could see from the face that his spirit had not been lost. I knew, that, if I touched him, he would fall into dust—and yet, there was something unconquered in the face.The ghastly parable is obvious. Benét chose his revised title well, as, according to Biblical mythology, the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon along the Euphrates River was destroyed for pissing off God. Jeremiah 51:37: “And Babylon shall become heaps, a dwelling-place for dragons, and astonishment, and a hissing, without an inhabitant.” If the theme sounds familiar, it was later used in such dystopian films as Planet of the Apes, Mel Gibson’s Mad Max series, The Book of Eli, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” and novels by Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, and many others. There were post-apocalyptic efforts well before Benét wrote his Babylon tale (Poe, H.G. Wells, Mary Shelly), but there’s little doubt that Benét, well in advance of the nuclear age, was influenced by the growing menace of global devastation then sponsored by Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany. Brainerd Duffield adapted “By the Waters of the Babylon” as a one-act play in 1971.  Duffield theatrical version *** In his idiosyncratic posthumously published 1944 study America—more of an elongated essay than an actual history—Benét is relentlessly upbeat about his native land. He doesn’t fully ignore some of the nation’s many excesses (the war against Spain, slavery, Jim Crow, the annihilation of the American Indian), but neither does he fully apologize for them. As he celebrated his beloved nation, he had, I’m afraid, a partially blind eye: We have not become—as some feared we might become—a nation ruled by wealth and devoted to gain. We have not become—as some feared we might become—an anarchical mob. Nor shall we in the future. For we do not sit down quietly and accept injustice and wrong. At no time has there been an abuse in America that has not been exposed, cried out against, attacked by free-speaking Americans.But what would Benét think of a vocal minority who threatens to march on Washington with loaded guns, and who vow to use “Second Amendment remedies” if defeated at the ballot box? And how would he react when political parties, in states they control, pass laws to restrict and obstruct the right to vote or control the reproductive rights of women? In America he writes of his native land: It is partly the struggle between conservative and liberal, between people who think that things ought to stay pretty much as they are and people who want reforms and changes, between men who think the people have enough power and men who think they should have more. But it has been the struggle of a nation still striving, still learning, still trying to find out not what works best for just one class of people, but what works best for all the people.  Benét While Benét unabashedly adored his native land, perhaps naively, Bierce was contemptuous—as witness his cynical doggerel: My Country ’tis of theeIn his day, Ambrose Bierce was the equivalent of a libertarian, skeptical of trends and anything newfangled, and outraged by an evolving language that put his cherished dictionary out of date. He saw preachers and politicians as much of the same ilk: eels “in the fundamental mud upon which the superstructure of organized society is reared.” Despite the current GOP’s anti-intellectualism, disdain for the arts, contempt of science, and devotion to religious superstition, Bierce would likely be a Republican today—although more from lethargy than commitment. While change came hard for him, he was an equal-opportunity scoffer. In his Hearst column “The Passing Show” of August 1, 1900, Bierce writes: I am no Democrat and have no wish to live under a Democratic administration, but if I were Bryan [perennial Democratic presidental candidate William Jennings Bryan] with Mr. Bryan's opportunity and powers I would within a week create such a conflagration in this land as would lay in ashes the last Republican hope of political successs—a conflagration that would burn away every partisan barrier, fusing all patriotic elements into a whitehot enthusiasm for flag and country and—Bryan.  Bierce the elder Benét did not appear to be overtly religious—he never clearly established his religious orientation—although some of his writing touched on religious themes. His prize-winning 1922 poem in The Nation, “King David,” led to unenlightened allegations of immorality and blasphemy for challenging the literal acceptance of the Old Testament. His story “Into Egypt” parallels the Nazi persecution of the Jews. In this tale, a mother, father, and their newborn child, the last of the so-called “Accursed People,” are forced to pass through a frightening military checkpoint. The three are, of course, Joseph, Mary, and Jesus. Benét’s radio play “A Child is Born” is a dramatic celebration of the birth of Christ, and his “Thanksgiving Day—1941,” read on NBC by Brian Donlevy, is nothing less than a prayer of gratitude. On the other hand, Bierce’s celebrated distaste for religion places him squarely into the ranks of atheists and agnostics. His hilarious jibes at religion are exemplified by his definition of a heathen: “A benighted person who has the folly to worship something he can see or feel.” That about nails it. *** There they are. Two writers separated by decades and temperament, Bierce essentially a product of the nineteenth century, Benét of the twentieth. It’s hard to imagine Bierce and Benét as drinking pals. Or Benét undertaking an ill-fated adventure into revolutionary Mexico. Yet we see in their writing parallels that not only elevated both to the pinnacle of Civil War authors, but who also had an agreeable arrangement with the weird tale—which has made them enduring. That’s saying a lot. Yet Benét is one up on Bierce in at least one regard: Bierce never had his name on a postage stamp. Not yet.  Portrait of Benét for the Postal Service by Michael J. Deas, 1998 Audio I was able to track down a number of recordings and broadcasts based on the works of Stephen Vincent Benét, which are posted here: Radio Broadcasts

Among the Sources Consulted

Benét, Stephen Vincent. America. New York, 1944. ___________________. Last Circle, The. New York, 1946. ___________________. Selected Letters. Charles A. Fenton, editor. New Haven, 1960. ___________________. Selected Works. Two Volumes. New York, 1942. ___________________. Tales Before Midnight. New York, 1939. ___________________. Tiger Joy. New York, 1925. ___________________. Thirteen O’Clock. New York, 1937. ___________________. We Stand United and Other Radio Scripts. New York, 1945. Bierce, Ambrose. Ghost and Horror Stories of Ambrose Bierce. E.F. Bleiler, editor. New York, 1964. ______________. Short Fiction of Ambrose Bierce, The. Three volumes. S.T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, and Lawrence I. Berkove, editors. Knoxville, 2006. ______________. Skepticism and Dissent: Selected Journalism from 1898-1902. Lawrence I. Berkove, editor. Ann Arbor, 1980. Fenton, Charles A. Stephen Vincent Benét, A Biography. New Haven, 1958. Forbes, David. “Ghosts in the Burning City: Benét’s Prophecies.” In Collhouse Magazine, April 14, 2008. [http://coilhouse.net/2008/04/ghosts-in-the-burning-city-benets-prophecies/] Izzo, David Garrett and Lincoln Konkle, editors. Stephen Vincent Benét: Essays on His Life and Work. Jefferson, NC, 2002. McWilliams, Carey. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. New York, 1929. Stroud, Parry. Stephen Vincent Benét. Twayne, 1962. © 2013 by Don Swaim

|

|

|

click to buy |