|

the AMBROSE BIERCE site |

|

the AMBROSE BIERCE site |

Once upon a time, a young Philadelphian named Emanuel Julius, who was caught up in the radical politics of the early twentieth century, journeyed to tiny Girard, Kansas (pop. 2500), to write for a socialist weekly, Appeal to Reason. There, he met a banker's daughter, Marcet Haldeman. They married and Julius adopted his wife's maiden name to become Emanuel Haldeman-Julius. Emanuel, borrowing from his wealthy wife, purchased Appeal to Reason and turned it into a mail-order publisher of tiny, cheap paperbacks selling an estimated five-hundred million over four decades.

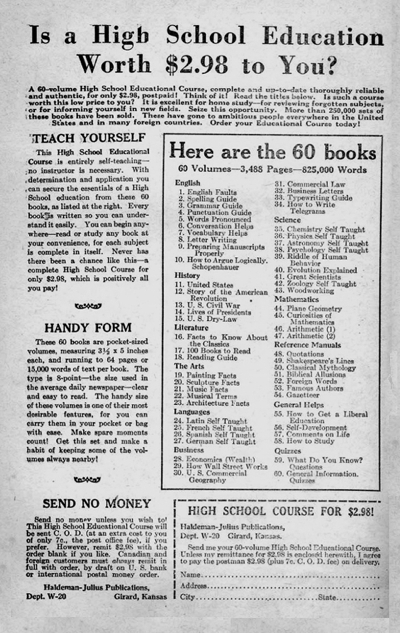

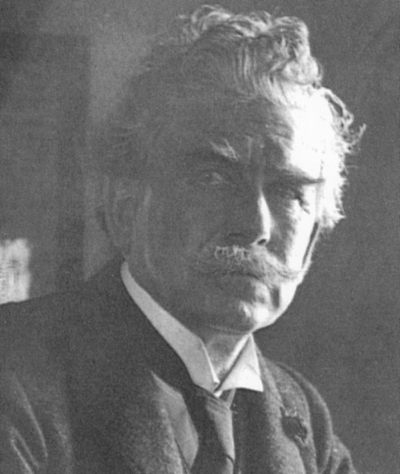

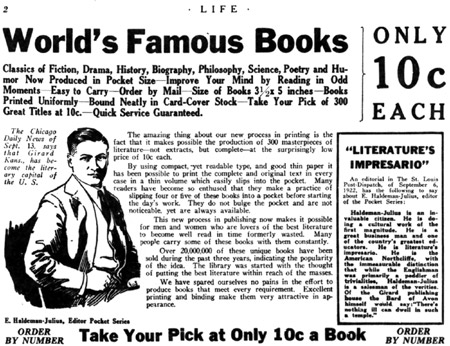

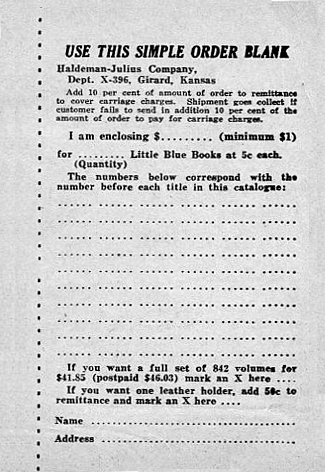

A storied beginning with a sad and somewhat mysterious ending. Operating a press that pumped out forty-thousand books each workday, and by sizing the books at a mere three and a half by five inches in stapled wrappers and limiting the page count to sixty-four, Haldeman-Julius was able to reduce the price from a quarter to fifteen-cents to a dime to a nickel. Because the covers were blue, mostly, they became known as Little Blue Books. Title Number One was the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Number Two was The Ballad of Reading Gaol by Oscar Wilde.  Women working at Haldeman-Julius printing company. [photo: kansasmemory.org] To the average American, hungry for dirt-cheap culture, education, literature, and titillation, Haldeman-Julius supplied a need. His titles ranged from The Art of Kissing to The Communist Manifesto to Elementary Plane Geometry Self Taught to What Every Married Woman Should Know. Authors ranged from Alexander Pope to Nietzsche to Dostoevsky to Jack London. Plus hack work by free-lancers to whom Haldeman-Julius paid $50 for each 15,000 words. The company became the world's preeminent mail-order business with franchise stores in several major cities and sales from vending machines. Haldeman-Julius also published packages of books aimed at readers lacking high school or college training, with such ads as "Would You Pay $2.98 for a High School Education?"  Emanuel and Marcet were active partners, and both wrote for the Blue Book series. One of Marcet's books was titled Marcet Haldeman-Julius's Intimate Notes on her Husband. She also co-edited a standard-sized magazine, the Haldeman-Julius Monthly. Rolf Potts, in an extensive article in The Believer, September 2008, quotes H. L. Mencken as saying "the editing and printing [of the books] show all the usual Socialist incompetence... It is not agreeable to think of a poor man laying out money for such garbage..." But Potts also cites a McClure's magazine article noting that Haldeman-Julius had been called "The Henry Ford of Literature, "the Book Baron," "Voltaire from Kansas," and "the Barnum of Books." Enter Ambrose Bierce.  Bierce While their lives overlapped—Bierce born in 1841, Haldeman-Julius in 1889—they were not acquaintances. Aside from their religious ambivalence, it is fair to say that their politics, Bierce a sometimes stuffy libertarian and Haldeman-Julius a liberated left-winger, would have kept them far apart even if they had been contemporaries.

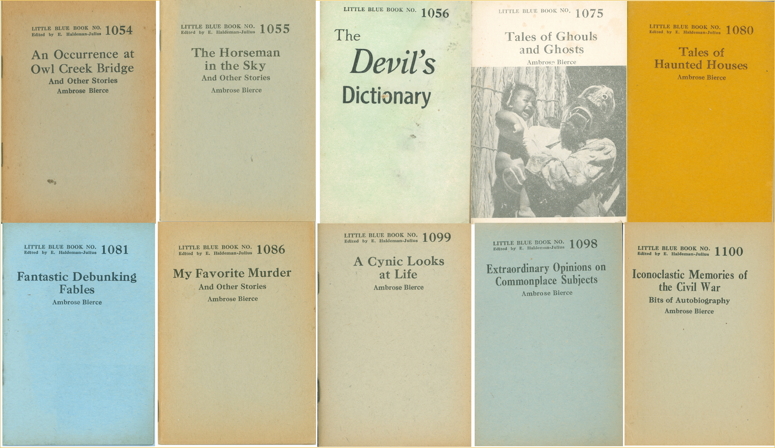

Collectors of Little Blue Books exist, but for a completist, if there are any, the task must be enormous. My job was simple. I needed to locate just the ten Bierce titles related to this article, decades following their availability by a nickel from vending machines.  Little Blue Books vending machine, 1939. [photo: haldeman-julius.org] In all, Haldeman-Julius published some 2,300 Little Blue Book titles between 1923 and his death in 1951. Roughly, some 200 titles were issued each year. There were other Haldeman-Julius book series as well, such as the People's Pocket Series, Five Cent Pocket Series, The Appeal's Pocket Series, etc.  Luckily, there is an invaluable online Haldeman-Julius database, which details every title by number, author, how to date them, historical notes, collector resources, and photos. It can easily be searched.But dating the Little Blue Books is maddening. One can check the numbers chronologically, of course, but some titles were republished over the years.

Most of the Bierce titles appear to conform, although some of the covers have faded to brown. A 1950s reprint of The Devil's Dictionary, No. 1056, lacks Bierce's name on the front cover. At least one title, Tales of Ghouls and Ghosts, No. 1075, has a slick pictorial cover unlike the standard Little Blue Books, suggesting it was republished. A librarian at the University of Buffalo wrote that because millions of the Little Blue Books were sold, they have no significant value. Others would disagree. In fact, the ephemeral nature of the books may deem them rarities. Near the end of his life, Haldeman-Julius said with some accuracy, "It may even go so far as to say that I changed the reading habits of America and created millions of new readers for the book publishers who followed me." The Haldeman-Julius story ends badly.  Haldeman-Julius family. [photo: The Believer] Both Bierce and Haldeman-Julius are long gone, but their names and work live on, in part because of The Little Blue Books.

References

Gibbs, Jake. Little Blue Books Bibliography, Lexington, Ky, 2019. Haldeman-Julius.Org. http://www.haldeman-julius.org Herder, Dale M. "Haldeman-Julius, The Little Blue Books, and the Theory of Popular Culture," Journal of Popular Culture, vol. IV, no. 4, spring 1971. Johnson, Richard Colles and G. Thomas Tansell. "The Haldeman-Julius 'Little Blue Books' as a Bibliographical Problem," The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 64, 1970. Joshi, S. T. and David E. Schultz. Ambrose Bierce: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary Sources, Greenwood Press, 1999. Palmer, W. P. "Emanuel Haldeman-Julius and the Education of the Poor of America," paper, IPS-USA Conference, New York, July 2006. Potts, Rolf. "The Henry Ford of Literature," The Believer, September 2005. to be published in 2016 by Hippocampus Press, New York.

|