The Joshi Q&A

the AMBROSE BIERCE site

The Joshi Q&A

the AMBROSE BIERCE site

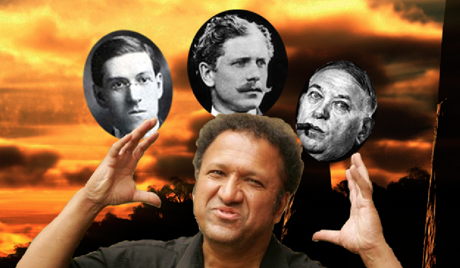

S. T. Joshi. Scholar, biographer, bibliographer. Expert on Bierce, Lovecraft, Mencken, and many others. Author or editor of -- or contributor to -- nearly 200 books. Authority on the history and creation of weird fiction. Don Swaim, founder of The Ambrose Bierce Site, interviewed S. T. Joshi, who lives in Seattle, in May 2013.  Q. Your parents were Indian-born academics who brought you to America when you were five. What in your parental upbringing influenced your particular literary interests? A. My mother was a mathematician and my father an economist, so it would not seem immediately evident that they contributed to my literary development. But as a matter of fact, both of them (especially my father) were very well read in English literature, and we always had books, reference works (including the 14th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica), and musical recordings in the house. But my parents' influence was fairly general -- an expectation that I would enter into some kind of intellectual profession (probably a teacher or professor) and that I would excel in my schoolwork. Q. Who were your childhood literary heroes? A. The curious thing was that, up to the age of ten, I didn't care to read at all. I did well enough in school, but all I wanted to do was to play sports -- baseball, football, soccer, you name it -- with my neighbourhood buddies. But my older sister, Nalini, became alarmed at my lack of independent reading, so she dragged me to the public library. Somehow I latched on to C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia.

Being utterly ignorant of even the rudiments of Christianity, I was entirely unaware of the heavy Christian symbolism in those books -- I merely read them as entertaining stories. But they got me reading -- and also perhaps fostered my taste for fantasy and horror. Q. I take it that you discovered the horror writer H.P. Lovecraft when you were a teenager. What was it about Lovecraft's work that inspired you? A. I came upon Lovecraft's work at my public library, probably around the age of thirteen or fourteen. I had previously found horror more to my taste than fantasy or science fiction -- I think the first horror I read were some anthologies for young adults compiled by Rod Serling and Alfred Hitchcock. But Lovecraft opened up an entire universe of fascination and horror unlike anything I had ever read. Because his major stories are interlinked in subtle and complex ways, they seemed to add up to more than the sum of their parts. His dense, richly textured language acted upon me as a kind of incantation, even though I probably didn't understand all the long words he used. (On my second or third reading of Lovecraft, I sat at my desk with a dictionary at hand!) Q. When and under what circumstances did you decide to become a literary person yourself? A. I believe I wrote my first short story at the age of fourteen. This was 1972. It was called "Murder" and was a first-person account of a murderer who suffers a supernatural revenge from his victim. I still have the pencil draft! It was published in my high school's annual literary magazine, but I don't seem to have a copy of this. I went on to write hundreds of short stories during my four years of high school, covering thousands and thousands of pages; I also wrote a full detective novel and about half of a second before abandoning it. (I had become a devotee of detective stories by no later than the age of thirteen, reading pretty much the complete works of Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Margery Allingham, and other classic detective writers.) My short stories were predominantly horror, although with a fair number of mysteries mixed in. I embalmed some of them into quasi-print in the monthly literary magazine I edited during my junior and senior years -- The Forum. I still have every issue! The republication of this juvenilia (which also includes dozens of incredibly silly poems) would probably force me to retire to Mongolia in mortification. Q. What was the connection, if any, between Lovecraft, who lived in Providence, Rhode Island, and the fact that you chose to study at Brown, which is also in Providence? A. I'm reminded of a comment that Robert Bloch once made: "Lovecraft was my university." By this Bloch meant that, although he himself did not attend a university, his four-year correspondence with Lovecraft (1933-37) opened up so many different avenues of intellectual inquiry that he felt he had gained the equivalent of a college education. In my case, Lovecraft literally led me to my university. My "scholarly" interest in Lovecraft began when I was no older than 17. This was in 1975, when L. Sprague de Camp's Lovecraft: A Biography came out. I found it fascinating and compelling (not recognising its many flaws at the time) and also saw that even I, as a humble high school student, could make some contributions to Lovecraft scholarship.

The field was in a very rudimentary state then. That summer (just before I entered senior year of high school), I began compiling a volume that would eventually become H. P. Lovecraft: Four Decades of Criticism (Ohio University Press, 1980). I think it was the de Camp biography that alerted me to the fact that Brown University was the major repository for Lovecraft materials -- manuscripts, printed publications, and much else. So I knew I had to go to Brown! I was luckily accepted there (also at Yale), and so I began my college career in the fall of 1976. Q. You're well known as a bibliographer -- and your Bierce bibliography has been a gold mine for my Ambrose Bierce Site (cited on the site's Chronology page). Tell me about your early efforts in criticism and bibliography. A. My bibliography of Lovecraft (Kent State University Press, 1981) began almost accidentally. Even during my senior year in high school, I began inquiring among academic publishers as to whether they wanted to publish my Four Decades of Criticism (it had a different title at the time). Kent State said no, but at the time it had a distinguished line of bibliographies called the Serif Series of Bibliographies and Checklists. Kent suggested that I do a bibliography for that series. I knew very little about bibliography, but I knew that a new Lovecraft bibliography was much needed. All previous bibliographies had been compiled by "fans" who really knew very little about proper bibliographical method. I initially felt that I would merely act as a kind of editor of the Lovecraft bibliography, the actual work being done by my older and more experienced colleagues in the field; but in the end -- and especially as I began consulting the vast resources of the H. P. Lovecraft Collection at Brown University -- I did a large part of the work myself. I never thought I'd do another bibliography -- it is one of the most labor-intensive tasks in literary scholarship -- but a decade later I did a bibliography of the great Irish writer Lord Dunsany (1993). My scholarly interest in Bierce, which began in the mid-1990s, made me realise that a new bibliography of Bierce was a crying necessity, so David E. Schultz and I compiled one. Since then, I have prepared bibliographies of Gore Vidal (2007) and H. L. Mencken (2009); a vastly expanded version of my Lovecraft bibliography came out in 2009. Forthcoming are bibliographies of Clark Ashton Smith, William Hope Hodgson, Arthur Machen, and the California poet George Sterling. Q. Talk about your first published work and your reaction when you first saw it. A. The first article of any consequence I published was "Lovecraft Criticism: A Study." This was in fact a portion of what became my introduction to H. P. Lovecraft: Four Decades of Criticism, but it was published in a fanzine called The Miskatonic in 1977. This was a mimeographed, stapled journal that probably did not have more than 50 readers, but it tickled me to see my work disseminated among readers who would be most likely to appreciate it. My first book, if you want to call it that, was a collection of rare Lovecraft materials, Uncollected Prose and Poetry (Necronomicon Press, 1978) -- a booklet marred by a shocking number of typographical errors. I am a rotten proofreader of my own work. But my first real book was the Four Decades of Criticism, copies of which reached me just as I graduated from college. That was a true thrill! I guess not very many people publish a book with an academic publisher by the age of 22, and it launched my career. Q. You had some early experience editing magazines and working for a publisher in New York. Will you describe it? A. Well, the only magazine I edited in my early career was Lovecraft Studies (1979f.). While at Brown (1976-82; I got a B.A. in 1980 and an M.A. in 1982), I gathered around me a group of like-minded individuals devoted to Lovecraft, one of whom was Marc A. Michaud, who had founded a small press, Necronomicon Press, while he was in high school. He, I, and others felt that the time was right for a scholarly journal devoted to Lovecraft. We actually held some discussions with officials at Brown to see whether the university would be interested in sponsoring it; but it seemed unlikely that, even if it did so, it would allow two undergraduates to edit it. So we published it ourselves. The first issue came out in Fall 1979, in 250 copies. It quickly sold out, and copies of that issue are now going for a pretty penny. The journal did become the chief organ for Lovecraft scholarship during its run (it folded around 2005). I actually typed out the pages of the first 15 or 16 issues on my IBM Selectric Typewriter! After that, Michaud set up the issues on his newly acquired computer...

After Brown, I thought of pursuing a Ph.D. in Classical Philosophy at Princeton (I had gravitated to the study of Latin, Greek, ancient history, and ancient philosophy while at Brown); but I didn't like Princeton, and also didn't like the idea of spending my life teaching at a university. So after two years at Princeton (1982-84), I left. Luckily, I found employment with a small company in New York called \, which was engaging in an ambitious program of reprinting literary criticism under the general editorship of Harold Bloom. I learned an immense amount about general literature and literary criticism while at Chelsea House (1984-95). Q. Lovecraft appears to have been the springboard to your interest in other writers of weird tales, notably Ambrose Bierce -- or is that an over-simplification? A. This is quite right. One of the seminal books I have kept at my bedside, so to speak, is Lovecraft's essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927). This short (30,000 words) treatise treats the full range of supernatural fiction from antiquity to the 1920s, and it has been a constant fund of inspiration. Lovecraft had a great admiration for Bierce (in spite of his disapproval of Bierce's spare prose style, which he referred to unkindly as "prosaic angularity"!), so of course I had to explore Bierce. I probably did so even in high school, but certainly in my early college years. Lovecraft also identified Arthur Machen, Lord Dunsany, Algernon Blackwood, and M. R. James as the "modern masters" of weird fiction, and I have done considerable research in them also.

Q. H.L. Mencken, whose work you've also addressed, gave up on fiction. And he wrote no weird tales. You recently edited a collection of Mencken's early stories (Bluebeard's Goat), but he's on a somewhat different level from the others, isn't he? A. My interest in Mencken, seemingly at odds with my other literary interests, can nonetheless be traced ultimately to Lovecraft. I have, however, long maintained an interest in literary satire, beginning with Aristophanes and Juvenal and proceeding to Jonathan Swift, Bierce, Twain, Nathanael West, and Gore Vidal. But the Lovecraft-Mencken connection is interesting, if indirect. One of Lovecraft's great colleagues was Clark Ashton Smith, a scintillating poet and fantasy writer from California. I was very taken with his poetry (less so with his fiction), and discovered that he himself had been tutored as a young poet by George Sterling (1869-1926). I then found Sterling of consuming interest also. I was looking for ways to promote Sterling as a poet and general man of letters, and found that he had had an extensive correspondence with Mencken. I found both sides of that correspondence and prepared an edition of it (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2001). I chiefly did so as a way of trying to get Sterling back on the literary map; but in the process, I became so enamoured of Mencken that I plunged into research on him also. In fact, I have transcribed the totality of Mencken's published writings -- books, magazine articles, and more than 5000 newspaper articles -- on my computer, to the tune of 12 million words!

Q. Explain the importance of Lovecraft in influencing the weird fiction genre overall, and his parallels with similar authors. A. Lovecraft was unique in being both a tremendous innovator in weird fiction and in being one of the most acute theoreticians in the field, even though many of his theoretical comments are found only in letters. I have learned a great deal about the history and theory of weird fiction from Lovecraft, and have used many of his theoretical comments as the foundation of my own views, in such works as The Weird Tale (1990) and Unutterable Horror: A History of Supernatural Fiction (2012). As for Lovecraft's fiction and its influence on subsequent writing, this is immense. It goes well beyond the (mostly inferior) imitations of Lovecraft's pseudomythological framework (the Cthulhu Mythos) and extends to the whole range of "cosmic horror." Lovecraft's chief innovation was a fusion of traditional supernatural fiction with the burgeoning field of science fiction, and in his influence on certain science fiction writers (Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, etc.) is pronounced, although still not adequately discussed by scholars.

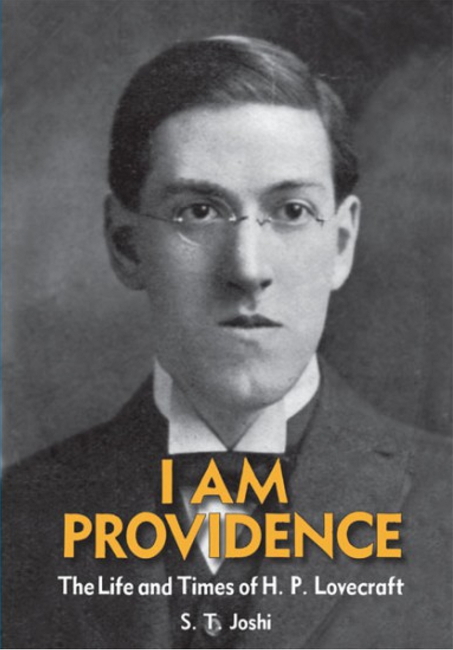

Q. There appears to be a pattern regarding some of the writers with whom you have an interest, such as Bierce and Mencken, both considered skeptics if not actual atheists. How does their contempt for religion parallel your own? A. I suppose I have been consciously or unconsciously drawn to religious skeptics, beginning with Lovecraft himself, whose forthright advocacy of atheism (chiefly in his letters) was hugely influential with me. But this is not exclusively the case. Arthur Machen was a devout Anglo-Catholic, and Algernon Blackwood was a kind of Buddhist mystic or pantheist. I quite frankly don't have much respect for the religious views of these authors, but that doesn't have any bearing on my admiration for them as writers of weird fiction. Q. You've not only written about atheism, but I understand you're considering a multi-volume history of atheism. Tell me about that. A. The task of writing a comprehensive history of atheism may be the last major scholarly project I undertake -- that is, a project on the scale of my large biography of Lovecraft (I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft [2010]) and my two-volume history of supernatural fiction, Unutterable Horror. But I have so many other obligations at the moment that I am finding it difficult to carve out the time even to begin the research on it. My training in classical philosophy will come in handy when I treat the ancient philosophers (especially the Presocratics, the Atomists, and the Epicureans), and I have done my share of work on the 18th-century philosophers (I have just assembled a selection of their writings on religion -- The Original Atheists, forthcoming next year from Prometheus Books). But the amount of work involved is overwhelming. In spite of the fact that I have no day job, I find myself pulled in many different directions, and various interests in weird fiction may keep me from undertaking the history of atheism for some years.

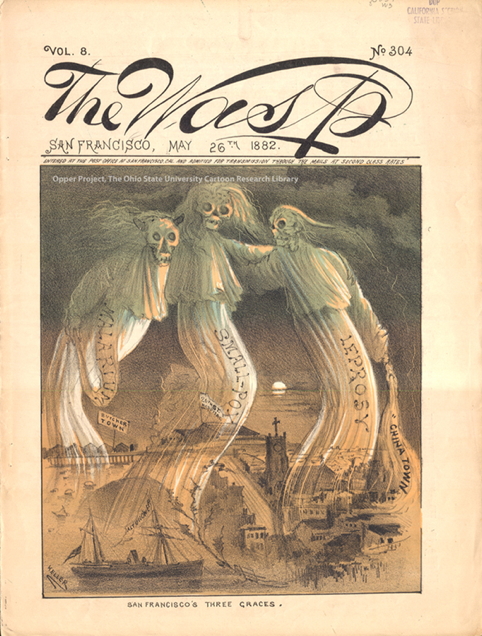

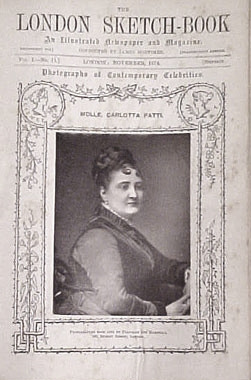

Q. How does atheism shape your own life? A. This is too large a question to answer in a small space. Some hints of the answer might come from the journal that I have been editing since the summer of 2011, The American Rationalist. In that journal I have a regular column, "The Stupidity Watch," which allows me to express Biercian cynicism at the incredible stupidity of religion and religious phenomena (also political phenomena, mostly of a Republican sort). The fact that I never received any religious training at all as a youth was to me a (pardon the pun) godsend. It cleared my mind, and I was not forced to undergo any painful "deconversion" from religious belief to secularism, as I know many of my friends and colleagues have gone through. I frankly admit that I have not the slightest understanding of the religious mentality, and do not know how belief in a god can even provide the psychological comfort that it apparently does provide to millions. Q. Your bibliography of Bierce, which you assembled with David E. Schultz, seems to have been a mammoth undertaking. How did you know where to start and what prompted you to do it in the first place? A. One of the tasks I have always felt to be of immense importance when studying an author is to assemble the totality of his or her work -- and, ideally, to have that work available electronically for ease of reference. David E. Schultz and I have jointly transcribed the totality of the work of H. P. Lovecraft, George Sterling, Bierce, and some other authors, and I myself spent nine years transcribing Mencken's work. Schultz and I knew that Bierce's newspaper work, in particular, had never been adequately recorded in previous bibliographies, so we spent many months combing page by page through the Argonaut, Wasp, San Francisco Examiner, and other papers to look for Bierce's work -- with the understanding that some of it was published anonymously or pseudonymously.  Bierce contributed to The Wasp from 1881-1886 and launched his "Devil's Dictionary" there. Probably there is even more Bierce work in these and other periodicals than we have listed in our bibliography, but at least it is a start. We did indeed end up transcribing the totality of Bierce's writing -- which came to at least 6 million words. Much of this had to be done by brute typing, since the copies of newspaper articles we secured were so poor that they could not be adequately scanned or read by OCR software. But somehow we finished the job. Q. How much travel to the various Bierce literary archives was involved, and how did you relate with the librarians? A. Schultz lived in Milwaukee, and he somehow discovered that the library of St. Cloud State University in Minnesota had a full run of the Examiner -- at least, of the period when Bierce was contributing to it. We took two separate trips to St. Cloud to secure copies of this material. We made so many microfilm printouts that we ended up breaking one of their machines! But that was only one phase of the work. I recall going up and down the state of California in the summer of 1998 visiting the major repositories of Bierce holdings -- the Huntington Library and Art Gallery in San Marino; the Bancroft Library (University of California) at Berkeley; the San Francisco Public Library; and elsewhere. (I had earlier spent many hours at the New York Public Library, whose Berg Collection has substantial Bierce holdings.) I was also attempting to get copies of all of Bierce's manuscript letters, and ended up writing to dozens of libraries around the country for these copies. Most of the librarians I worked with were unfailingly courteous and helpful, and I could not have done this work without their assistance. Q. As the editor of an Ambrose Bierce website, I've found your Bierce bibliography invaluable. A mere checklist it is not. But what is the process necessary to assemble such information and in such detail -- and what are the chances of error? A. I hope there are no errors in the Bierce bibliography, but there are probably omissions. Indeed, a few years after we published the bibliography I stumbled upon a periodical called the London Sketch-Book, which turned out to have published the first versions of the story "The Night-Doings at 'Deadman's'" and the important essay "What I Saw of Shiloh" in the 1870s, years before they appeared in American magazines.

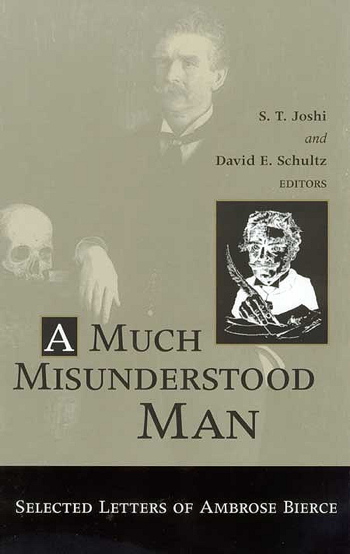

At least two of Bierce's early stories appeared in the short-lived London Sketch-Book, 1874-1875. Also, there is evidence that Bierce wrote more work (anonymously) for the Argonaut than we had identified. This is going to be very difficult to identify conclusively, because one has to work solely on internal evidence -- a knowledge of Bierce's general style and subject matter. Schultz and I also debated on how to arrange the information. My Lovecraft bibliography (as well as those for Dunsany and others) breaks down the author's work by genre (novels, fiction, poetry, essays, etc.); but this proved unwieldy for Bierce, given that he tended to work almost exclusively for a given paper for long stretches of time. So, in the section of "Contributions to Periodicals," we opted for a strictly chronological approach. So the arrangement of every bibliography has to be tailored to the nature of a given writer's work. Q. Do you envision adding to the bibliography? A. We actually found some additional Bierce material even while the bibliography was in press, so we quickly prepared an appendix listing this material. Probably the best way to present a bibliography these days in to do so online. A bibliography becomes outdated the moment it is printed. But we put so much time and effort into the task that we are reluctant to give the material away free on the Internet. Those naïve people who think that "Information wants to be free" have no conception of how much time, effort, and money it takes to generate this information. If I were funded by a grant or had a wealthy patron, in the manner of the 18th century, I would be happy to give my work away for free! Q. How did you even know where to start to locate all of this Bierce material? A. There are, as I have suggested, dozens, perhaps hundreds, of libraries that own Bierce materials of some sort or other -- books, manuscripts, etc. As is always the case in compiling a bibliography, the first 90% of the material takes 10% of the time, and the last 10% takes 90% of the time. For manuscripts, there are reference works that identify the libraries that own Bierce materials; you then have to write to each individual library to find out exactly what they own. Sometimes this information is available on the library's website; sometimes it isn't. Print and online library catalogues identify the libraries that own rare works by Bierce. We have actually obtained microfilm reels containing the entire runs of periodicals such as the Wasp or the Argonaut for the period that Bierce wrote for them. This would be prohibitively expensive in the case of the Examiner, since one would have to obtain dozens of microfilm reels; so one has to know where one can find runs of this magazine in libraries. Increasingly, old newspapers and magazines are being put online, so the work should be much easier in future. Q. When you assembled the material, did you photocopy it, scan it, take written notes, or what? A. As I've mentioned, we did obtain microfilm printouts of the Examiner material -- mostly from St. Cloud, but also some from elsewhere. One interesting fact is that Arizona State University has the research papers of Bierce scholar Ernest Jerome Hopkins, and the library provided us with photocopies of some of his research. Bierce scholar Mary Elizabeth Grenander donated her papers to the library of the State University of New York at Albany, and I once went there to look through it. She had been planning an edition of Bierce's letters, and her materials contained letters that I was unaware of. That was very helpful. Purdue University has the papers of Paul Fatout, and there is some fascinating material there -- including old prints of Bierce's fearsome-looking relatives! Most of our work was done before scanning was convenient or accurate, so to this day I still have a huge file of photocopies and microfilm printouts of Bierce's work in newspapers and magazines, along with photocopies of Bierce's unpublished letters. Q. When you collaborate with Schultz, how do you coordinate? In other words, who does what, who writes what? A. Over the years, Schultz and I have worked out a pretty efficient way of collaborating on our multifarious projects, whether it be Bierce or Lovecraft or other things. He is far more computer-savvy than I am, so I leave it to him to prepare electronic files -- or at least to fine-tune them. But since he has a day job that is quite onerous, he does not have much time to go on research trips, so I have done the lion's share of the legwork in hunting up Bierce materials in libraries. Nowadays, of course, much of this work can be done remotely through the Internet or by contacting librarians via e-mail, who will then send you material electronically.  Joshi and his frequent collaborator David E. Schultz in Milwaukee (Photo by Mary K. Wilson) In terms of our annotated editions of Bierce's writings, Bierce did nearly the totality of work on the Unabridged Devil's Dictionary, which really shouldn't even have my name on it; if I did 10% of the work, I'd be surprised. But I suppose I've done a slight majority of the work on some of the other books. Schultz also tends to be more of a researcher (especially via the Internet) than a writer, so I have written most of the introductions and other commentary in our books -- with, of course, the exception of the Unabridged Devil's Dictionary. I confess to be rather proud of the lengthy introduction on Bierce's political thought in The Fall of the Republic and Other Political Satires (2000), and may reprint that piece as a separate essay sometime. Q. How do you and Schultz communicate? Phone, fax, email, etc? A. Our communication is nowadays almost exclusively via e-mail. Before that, we used to spend hours talking on the phone on all manner of subjects. We still do so occasionally, but time for both of us is short, and we don't talk as much as we would like. Schultz also doesn't care to travel much, so I've bearded him in his den in Milwaukee on several occasions. He and his wife Gail are unfailingly kind hosts. On our last visit, my girlfriend Mary Wilson took Gail out to a movie while David and I spent four or five hours talking shop (chiefly about our edition of Clark Ashton Smith's poetry).  Q. To what degree do the librarians at the various archives assist you in assembling your data -- or are you on your own? A. Most librarians are, of course, not specialists in Bierce's work, so they could have no role in the assembly or arrangement of the Bierce texts; but most have been extremely cooperative in providing materials or allowing us access to their holdings. Q. You and Schultz have digitized millions of words written by Bierce. Recently, Delphi Classics published online (for $1.99) what it says is Bierce's complete oeuvre, 4,228 pages. Is this an accurate claim -- and if so is it a help to you or does it cut into your own work? A. This is the first I've heard of this item. It looks impressive, but it seems largely a reprint of material in Bierce's Collected Works (1909-12), with some other material added. Our count of Bierce's complete published writings comes to 6 million words; at 400 words a page, this would come to 15,000 pages, or more than three times the size of this Delphi edition. This count doesn't include 500,000 words of unpublished letters, which would add another 1250 pages. These fly-by-night, unauthorised, and textually unsound electronic or print-on-demand editions will have no bearing on our eventual scholarly edition of Bierce's collected writings. Q. Over the years, there have been four volumes of Bierce letters -- one your own A Much Misunderstood Man (the others being Sterling's, Pope's, and Loveman's). But I understand that in terms of Bierce's letters only the surface has been scratched. Tell me about that. A. As I mentioned, the totality of Bierce's letters, published and unpublished, comes to just under 500,000 words. I have found the original manuscripts of nearly all the letters in Bertha Clark Pope's The Letters of Ambrose Bierce (1922) with the exception of the letters to Bierce's niece Lora, which appear to be in private hands. (But in this instance, I can rely on M. E. Grenander's transcripts of these letters, which are found in her papers at Albany.) My edition (A Much Misunderstood Man) contained only about a quarter of Bierce's letters, as did Pope's (and many of those letters were abridged). We also have both sides of the correspondence between Bierce and George Sterling, Herman Scheffauer, H. L. Mencken (a small correspondence -- not more than 6 letters on each side), and a few other correspondents. The totality of Bierce's letters (which would require at least 50,000 words of notes and commentary) would probably fill 3 volumes or 2 very large volumes. The problem is that many academic publishers are now strapped for cash and can't take on big projects of this sort without some kind of grant. So I may end up having to publish these letters with a small press like Hippocampus Press, hoping that the edition ends up in libraries, as it should.

Q. How would Bierce scholarship be advanced by publishing these additional letters or might it be an overload? A. Bierce played it pretty close to the vest even in private letters, but they nevertheless reveal many facets of his life and personality that don't come out in his stories, essays, or journalism. He had a tendency to engage in harmless flirting with nearly all his women correspondents -- and, contrary to the standard image (which as a matter of fact is largely true, at least as far as his public statements are concerned) of Bierce as an opponent of women's rights or even as a full-fledged misogynist, he exhibited considerable respect for the intellect and other qualities of some of his women correspondents, such as Ray Frank (a Jewish woman who became a pioneer in the Zionist movement), Blanche Partington, and others. His correspondence with George Sterling reveals him as a careful student of poetry and a skilful tutor of a young poet. Letters to longtime friends such as C. W. Doyle and S. O. Howes reveal a warmth and even a tenderness very far from Bierce's cultivated image as a curmudgeon. Q. There have been some blithely superficial notions about Bierce, that he was cynical, bitter, angry, quick to alienate his friends, etc., but in your reading of Bierce's letters, what conclusions have you drawn about the man? A. Well, some of those notions aren't all that far from the truth, although the letters certainly present a more nuanced portrayal. Toward the end of his life, Bierce did seem intent on discarding old friends such as Sterling and Scheffauer, although he seemed to have good reasons for doing so. Scheffauer had become very envious of Bierce's promotion of Sterling as a poet rather than himself, and he wrote some very harsh things in print about his former mentor. So Bierce had little option but to give him a stern dressing-down and cast him off. His letters to William Randolph Hearst provide fascinating insights into the difficulties of working for this powerful newspaper tycoon. And the letters to Walter Neale supply invaluable glimpses of how the Collected Works came to be compiled. Q. How do you assess Bierce's influence on the supernatural genre and literature in general? A. Bierce's influence on horror literature was limited but significant. He virtually created what I have called "satirical horror" -- horror (chiefly of a non-supernatural sort) that pungently underscores human failings by means of psychological terror. I have little doubt that he influenced such later writers in this form as Saki, L. P. Hartley, Shirley Jackson, and Roald Dahl. "The Damned Thing" is a pioneering tale that merged supernatural horror with science fiction. Bierce's influence on general literature is also well documented: his Civil War writings were immensely influential on such writers as Stephen Crane, Ernest Hemingway, and others. Q. Bierce was a prominent literary figure in his time, likely because of his association with the Hearst newspapers (which at the time actually published fiction and poetry). How do you measure his reputation now? A. I was happy to be asked to compile the volume of Bierce's writings in the Library of America series (The Devil's Dictionary, Tales, & Memoirs, 2011). This was the result of years of negotiation with the editorial staff of the Library of America as to exactly what should be in the book and how it should be arranged. There was no doubt in their minds that Bierce belonged in the American canon. The decision was regretfully made not to include Bierce's journalism, because there was simply no room for it amidst all the other material that had to go into the book. I am hoping that a second Library of America volume could include a substantial batch of journalism along with his fables (I think he was the best fabulist in English), a small modicum of his best poetry, and some letters. It seems that Bierce's reputation now rests largely on The Devil's Dictionary and on his role as an American satirist, more so than on his Civil War stories or his horror tales. This is perhaps a sound judgment, given that the entirety of Bierce's work is founded on the satirical principle and The Devil's Dictionary is the chief embodiment of it; but I suspect the tales will be read for many years as impeccable examples of the short story.

Q. Was his mysterious disappearance a help or hindrance regarding his literary reputation? A. Well, his disappearing into Mexico was certainly a fitting end for a writer of weird fiction! I think it lent a kind of mysterious sheen to Bierce's life and work that does add to his fascination as a writer. That said, there is still no satisfactory biography of Bierce. I hope to write it one day, but it will take me a while to find the time to do so. Q. One of the most important contributions to Bierce scholarship is your three-volume Bierce short fiction published by the University of Tennessee Press and co-edited by you, Schultz, and Lawrence Berkove. Aside from the Bierce work most commonly published, how did you locate all the material -- some of it obscure -- for this monumental project? A. Actually, the location of Bierce's fiction was not the difficulty. Bierce had embalmed much of it in the Collected Works (Volumes 1, 2, 3, and 8), although it struck me as strange that the political fantasies in Volume 1 ("Ashes of the Beacon," "The Land Beyond the Blow," etc.), which to my mind are some of Bierce's cleverest and most engaging works of fiction, were largely ignored even by his devotees. And, of course, his early volumes -- The Fiend's Delight (1873), Nuggets and Dust (1873), and Cobwebs from an Empty Skull (1874) -- had their modicum of short fiction, mostly of a comic or satirical sort. The difficulty lay in identifying what really constituted a "short story" as opposed to a sketch or a squib or what have you. There were many such items in the papers he wrote for during his London years (1872-75), notably in Fun. We had to gauge each item on an individual basis, trying to determine whether it was long enough, and had a sufficient narrative thrust, to be considered a true short story. Once the corpus of Bierce's short fiction was identified, then the rest of the job was relatively straightforward.

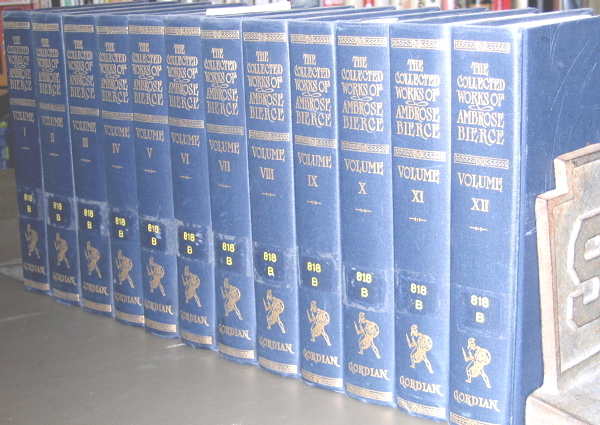

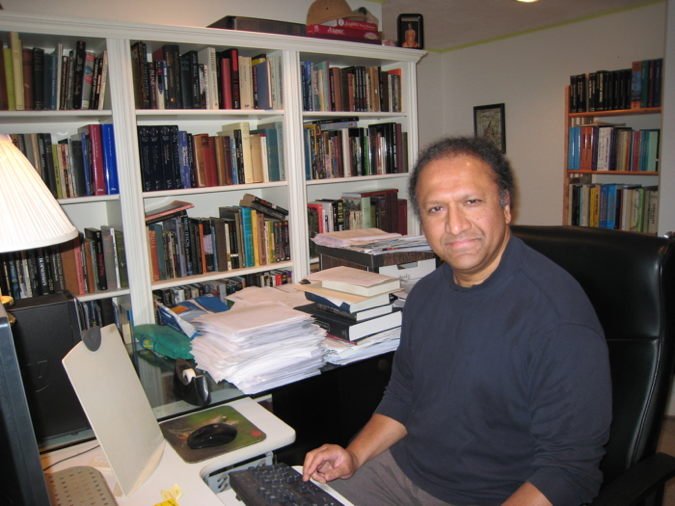

Q. Bierce himself published twelve volumes of his work starting in 1909. Why didn't this give you all you needed? A. Bierce's Collected Works (12 vols.) consists of only about 1 million words of text. If the totality of Bierce's published writing (exclusive of letters) comes to 6 million words, that would mean that it would 72 volumes! (Each volume of the Collected Works only fills about 80,000 words of text.) Bierce did not have much respect for journalism as "literature," even though his own journalistic writing has a very high literary value, in my judgment. Therefore, he disregarded nearly the entirety of this body of work when assembling the Collected Works. What he tended to do, in Volumes 8-11, was to carve out "essays" by extracting one or more sections from various newspaper articles and stitching them together. The result may be interesting enough, but it does not convey the true flavour of that journalism as originally published. So a comprehensive edition will some day be needed. Q. How did you, Schultz, and Berkove share your duties in assembling the story collection? A. This again was a fairly simple procedure. I was responsible for the establishment of the text, since I had all the relevant texts of Bierce's stories -- first appearances, first book publication, subsequent reprints in the Collected Works and elsewhere -- at hand, and I was an experienced textual scholar and had learned the principles of textual criticism from working with H. P. Lovecraft's texts. Schultz and I also wrote the initial annotations to the stories, which Berkove revised and corrected. Berkove was responsible for writing the general introduction, the introduction to each section, and the headnote to each story (actually, this was placed at the end of the story, just before the notes). Q. You and Schultz have edited a rather pricey three-volume set of poetry by George Sterling, a nearly forgotten minor poet, but notable because of his association with Ambrose Bierce (and perhaps Jack London and Clark Ashton Smith). Tell me about Sterling and the project. A. My interest in Sterling actually predates my (scholarly) interest in Bierce by a few years. Schultz and I began amassing texts by Sterling around 1995. It was then that I sent out letters to dozens of libraries asking them to send me the manuscripts of Sterling's poetry, letters, and other work in their collections. My interest in Sterling, as noted earlier, derived from the fact that he was a poetic mentor of Clark Ashton Smith. I felt he had been unjustly forgotten, so, aside from publishing the Sterling-Mencken letters, I also compiled a volume of his "weird" verse, The Thirst of Satan (2003), and his correspondence with Smith (2005). These books didn't exactly fly off the shelves, but my publisher (Derrick Hussey of Hippocampus Press) nonetheless committed to my plans for an edition of Sterling's collected poetry. I am tremendously grateful for his decision, for it is truly a dream come true for me -- and, I suspect, a big money-loser for him! Q. At $300 who is this work intended for? A. Well, this is a bit of a problem. I think there was a pre-publication price of $200, and we actually got some buyers for this. Sterling does seem to have a following in California, especially the Bay Area. Of course, we are hoping that libraries purchase the edition, and I suspect at least a few of them will.  George Sterling in 1907 with caricatures of himself, Bohemian Grove, California. Q. I may be wrong, but what I've read of Sterling's work seems to be, well, deficient. A Whitman he was not. I suspect Bierce over-valued Sterling's work. What is your assessment? A. I wouldn't rank Sterling as a great poet, but a very good one -- in the formalist, traditionalist school that basically ended with him (unless we include Clark Ashton Smith as a successor in this vein). He had the misfortune of coming to maturity at a time when poetry was undergoing a radical change away from formalism toward free verse (Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, etc.), deliberate obscurity (T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, etc.), and other such tendencies. I personally don't care for much of this kind of poetry and think Sterling was sound in adhering to formal rhyme and metre. Of course, he wrote too much and too easily -- he once said he could write a sonnet in 10 minutes, but the result is often facile. I think the best of his work is very good indeed. He was a master of the sonnet, and also a master of a kind of verse form that isn't practiced much anymore -- the verse drama. Lilith (1919) and Rosamund (1920) are two of his most impressive achievements. Bierce's praise of "A Wine of Wizardry" seems to me pretty much on target: it really is a remarkable expression of weirdness and fantasy in poetry. That said, Clark Ashton Smith easily surpassed Sterling in this regard and is without question the leading weird poet in English.  Clark Ashton Smith Q. Some of the literary figures you've focused on are hardly household names -- except to certain eccentrics like myself. George Sterling? Clark Ashton Smith? Three volumes of Bierce's letters? Is it possible to become discouraged performing such remarkable scholarship knowing there may not be a popular response? A. I haven't the slightest interest in a "popular response." I undertake projects because I deem them intrinsically worthy; and I am lucky to be in a financial position to do so. No one else apparently has the means or the resources to compile Sterling's poetry or Bierce's letters, so I might as well do it, otherwise it would probably not get done for years or decades. Most scholarly work is of pretty limited appeal anyway. My satisfaction comes from the fact that I have performed the job to the best of my abilities. Eventually this work will in fact seep into the mainstream literary community. It took decades of work on Lovecraft, by me and my colleagues, to get him recognised as a canonical figure in American literature. It may have seemed like a hopeless task at the beginning, but it eventually paid off. Q. You've come in contact with any number of literary figures. Lovecraft, Bierce, Mencken among them. If you could have dinner or drinks with just one literary luminary who would it be and why? A. Among all the writers I've worked on, I think Mencken and Sterling would probably have been the most entertaining to sit down with. It is no accident that both of them liked to drink! Lovecraft was a teetotaler, and, although he seemed by all accounts an intellectually brilliant and also a kind and generous man, his racist attitudes would bother me if they came up in a conversation. Bierce, I suspect, was a bit severe in person, although perhaps he let his hair down to people he knew well. But Sterling and Mencken were definitely "boon companions" who could always be guaranteed to give you a good time. Whenever some literary luminary visited San Francisco, Sterling made sure they had plenty of booze on hand (this was during Prohibition, remember), and even made sure that the figure in question (usually a man) had a nice girl to cuddle up with if he wanted one! Q. What prompted you to move from the East Coast and settle in Seattle? A. I came to Seattle in 2002 because my wife at the time was a native of Seattle and preferred to live there rather than in New York City, where I was living. I myself, having lived in the New York area for 17 years (1984-2001), was becoming a bit tired of the place -- it is a very exhausting city to live in, and the constant crowds of people one encounters every day was making me a bit of a misanthrope -- so I felt that the move was the right one for me. Well, my wife and I eventually divorced, but I am still here -- not only because I have now found a new partner here, but because I love living in a house (rather than an apartment, no matter how spacious), love working in the garden, love having a house full of cats (we have four) who go in and out as they please, and love being in a neighbourhood where people know each other and look after each other. In some ways it reminds me of the sense of community I experienced as a boy in Illinois and Indiana, although there are many more cultural refinements here. Q. What's Seattle like for a writer, and in particular yourself? A. I have to confess that, over the past several years, we Seattleites have quietly gloated that we have not faced the hurricanes, tornadoes, and other natural disasters that have afflicted the rest of the country. All we have to deal with is a constant misty rain (and even this is much exaggerated -- we get less annual rainfall by volume than New York City) and some traffic problems. Of course, there is the ongoing threat of an earthquake, but that would be a rare occurrence. I had always felt that I needed to be near a good university library in order to do my research. But, firstly, the nature of my work is changing, so that I am not engaged in "scholarly" research as much as I used to be (my main source of income these days is assembling original anthologies of horror fiction), and the advance of the Internet now allows me to find many research materials online instead of having to trudge to the library to find it. In any case, the University of Washington library is good enough for my purposes; but I rarely go there more than once a month these days. I confess that I do feel a bit cut off from my colleagues in the East and also, in some senses, from general American culture, which is also largely an East Coast phenomenon; but I can visit the East anytime I wish, and do so frequently.  Joshi and his companion Mary K. Wilson, New York City, view of George Washington Bridge  Joshi, Mary K. Wilson, Seattle, 2013 (photo by J. Klain) Q. How do your friends and acquaintances refer to you? S.T? Sunand? A. I adopted the literary name S. T. Joshi when I was about 15 -- that is what I signed nearly all my "publications" in my high school magazines. Beginning in college, I insisted that everyone call me S. T., and now everyone does, except my family. Q. How much affinity do you have for your native India or are you completely Westernized? A. My father insisted that I and my two sisters not be given any religious training as children, so I am as ignorant of the principles of Hinduism as most Americans. Because I came here at the age of five, I have had all my education in this country. I am -- slightly to my regret -- thoroughly Americanised and Westernised. I like to think of myself as Nietzsche's "good European" -- but find myself drawn to such American passions as football, baseball, basketball, and ice hockey! My one visit to India -- in 1994-95, when I went with my mother to scatter my father's ashes -- was an overwhelming experience: I felt simultaneously a foreigner and a native. But in reality, I know very little about India and frankly have not much interest in it. Q. Tell me about your office, working conditions, daily schedule, and mode of work. A. I have been working freelance since late 1995, when my publishing company (Chelsea House) went bust and threw us all out of work. It took me some years to establish myself as a freelance writer, but with the financial help of my mother I managed it. I now have an agent for the first time in my career, and she has helped me significantly in landing important (and remunerative) projects of various sorts. I am even writing some fiction -- short stories, a supernatural novel about Lovecraft (The Assaults of Chaos), detective novels, etc. But I doubt that I will ever make fiction writing a major part of my career. I now live in my girlfriend's house. Her basement is ideally suited for my work: it is lined with books, and my computer is situated in the midst of thousands of books, rows of file cabinets full of research papers, and other paraphernalia. If there was a kitchen down here, I might never emerge from my "man-cave"! But of course I have to play with the cats every so often.  Joshi in his man-cave, Seattle, 2013. (Photo by Mary Wilson) Being a freelancer requires considerable self-discipline, and I have to plan out each day depending on what projects are currently on the agenda. I also find that I do not have quite the energy I used to have, so I need a solid nap of half an hour or an hour in the afternoon, and I cease work around 5 p.m. I also feel the need to get some physical exercise, since my generally sedentary existence (and my fondness for food) has a tendency to make me put on weight. But I love setting my own schedule. I feel very lucky to have become financially stable enough to have this kind of life. I know many colleagues, far more talented than myself, who could probably do much better work than I could if they were in a similar position. But they are tied down to day jobs, so they can't be as productive as they wish. Q. Please describe your library and how it's organized. A. This house is a bit smaller than others I have lived in, so there was not room for my entire library of 5000+ books. So we built a shed in the back yard, with built-in bookshelves, to house some of my books. My library is rigidly organised. The largest is my collection of weird fiction, which is arranged strictly alphabetically by author, with anthologies at the end. This is of course here in the house, as it is the most valuable part of my library and I wouldn't wish to risk having it damaged by inclement weather in the shed. I also have my holdings of individual authors -- Bierce, Mencken, Lovecraft, Machen, Dunsany, Blackwood, Clark Ashton Smith -- here in the house. In the shed are (1) my collection of general literature, history, philosophy, etc.; (2) my collection of classical texts (Greek and Latin), which I can't bear to give up, even though I rarely read them anymore; and (3) my collection of detective stories, which I still read for enjoyment. (I am in fact currently writing a book called The Varieties of Crime Fiction.) Q. I saw on your website that you've published nearly 200 books. What's your favorite (or favorites) and why -- and how do you keep track of your own voluminous output? A. By some miracle, I kept a running bibliography of my writings from the beginning. If I hadn't, it would probably be impossible to assemble it now. So I think I'm reasonably up-to-date on my publications. One of my favourite books is The Weird Tale (1990), which seemed to me a "breakout" book for me in that I expanded my horizons well beyond Lovecraft to cover the whole range of weird fiction in the decades preceding his day. I also came up with an interesting theoretical framework for understanding "weird fiction," although I am now not wholly sure that framework can be applied universally to all weird writers. My biography of Lovecraft -- first published in abridged form as H. P. Lovecraft: A Life (1996), then unabridged and updated as I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft (2010) -- will probably be what I am chiefly remembered for as a scholar or biographer. I spent five years writing and researching Unutterable Horror: A History of Supernatural Fiction (2012), but I still think I left out some important writers.

Of course, my first atheist book (God's Defenders: What They Believe and Why They Are Wrong, 2003) and first political book (The Angry Right: Why Conservatives Keep Getting It Wrong, 2006) entertain me as instances of a virtual new genre -- "satirical criticism"! They are very Biercian in tone, although probably not in substance. Q. When that 200th book comes out, how are you going to celebrate? A. I had visions of having a big party at some swank nightclub or other such venue, with all my books laid out on a huge table (assuming I actually have a copy of each one of my 200 books!), but given that most of my colleagues live far away, I'll probably be satisfied with having a nice restaurant meal with my girlfriend and popping open some Champagne. But, in all honesty, the publication of a new book doesn't have quite the thrill that it once had. Still, I will probably have Hippocampus issue a little (or not so little) booklet called 200 Books by S. T. Joshi, giving complete contents of all my books as well as my other writings -- essays, introductions, reviews, etc. Q. It's clear you're a cat person. Ambrose Bierce defines cat as: "A soft, indestructible automaton provided by nature to be kicked when things go wrong in the domestic circle." I take it you do not agree. A. Well, I think Bierce was more welcoming of cats than that quotation suggests. Certainly, he liked cats better than dogs, which he loathed! My family in Indiana had a wonderful cat named Sherry (short for Scheherazade), and she was a delightful creature, even if a bit standoffish. One of the reasons why I became fascinated with Lovecraft was because I shared his devotion to felines. But when I left for college, and then settled in various apartments in the New York City area, I felt I could not keep a cat, since I would have wanted the cat to be able to go outside, and I also did a lot of travelling and didn't have anyone to look after it. Then I came to Seattle, and my wife had two exquisite cats, and I determined from then on never to live without a cat. We once had six cats -- four adults and two kittens. We suffered various cat fatalities over the years -- all extremely painful -- and when we parted, we had five. She took two and I took three. My girlfriend had one cat, and we were worried that he would freak out by the invasion of his domain by not one, not two, but three new felines; but he -- and they -- have adjusted reasonably well.  Joshi's Taffy ___________________ © 2013 Don Swaim

|

|

|

click to buy |