EXECRABLE! Ambrose Bierce’s Flop

The Little Johnny Stories

by Don Swaim

A man had a pet munky, and the mans boy hated the

A man had a pet munky, and the mans boy hated the

munky cause it done every thing which he done his self.

|

Question: When don’t Ambrose Bierce get no respect?

Answer: When it comes to his Little Johnny sketches, mostly ignored by his biographers and justifiably savaged by his critics.

Pigs is from ancient times. When a pig is fed it slobbers. But my father he says that when you are a going to be killed in the fall of the year whats the use of bein a gentleman jest for such a little time? Some pigs which go to fairs are so fat that you cant tell which is the head till you set down a bucket of slops, and then the end which swings around and points at it like a campus, that is it.

|

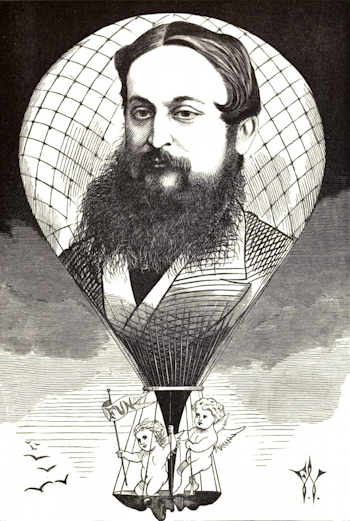

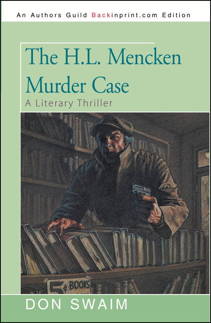

Above is Little Johnny narrating a story first appearing in London’s Fun, which was edited by Tom Hood (1835-1874), in the issue of September 12, 1874. Hood was both a mentor and perhaps an inspiration to Bierce during his three expatriate years in England.

Tom Hood, proprietor of Fun

Primarily told by a little boy in a nearly unfathomable dialect, it’s easy to understand why these pieces have been universally disregarded, and frequently condemned. The puzzle is why Bierce was so enamored of his Little Johnny character in the first place, why he persisted with it for much of his career, and why one of his great disappointments was being unsuccessful in publishing the tales in book form. That great authors such as Bierce may sometimes have failures is expected, but why Bierce persevered with Little Johnny for as long as he did has been an unanswered question.

Over Bierce’s long career, he concocted literally hundreds of Little Johnny stories — more appropriately called sketches (Bierce himself referred to them as “things” and “stuff”) — which appeared in Fun, the San Francisco Argonaut, San Francisco Wasp, San Francisco Examiner, New York American, and Cosmopolitan magazine.

Mister Gipple he says in Africa the natif n.....s eats nothing only but just grass hopper sittin on a stone, with its feets pulled in, all ready for to jump. The natif n....r he smiled sad, like a hi potamus and said: “How mournful to think that fellers which is like 2 brothers should distrust one another jest cause I am a n....r, which has a black skin, how can I help that?

|

Alas, as above, Little Johnny occasionally applied the dreaded N-word when referring to the black race, a now unpardonable lapse not duplicated in Bierce’s familiar, certainly non-racist, noble work, but still another reason the Little Johnny sketches are so terribly off-putting.

While Vincent Starrett, who published the first book-length study of Bierce in 1920, was more sanguine, asserting that the sketches “were popular and added color to his name,” others were hostile. Carey McWilliams, Bierce’s first major biographer, wrote that when Bierce launched his “Prattle” column in the Argonaut in 1877, “...he began to publish those ghastly animal humorous stories of his, in childish dialect, called ‘Little Johnny and his Menagerie.’ That Bierce could have written such stupid drivel has always remained a mystery. If Swift had written Boz [sketches by Charles Dickens under a pseudonym] it could not have been more surprising.”

Scholar Lawrence I. Berkove writes: “Several dozen of his abominable Little Johnny sketches intended to be comical unedited observations of a little boy, which Bierce took a perverse and inexplicable delight in writing during his entire career, appear in 1874 and 1875. Although now almost unreadable, they are at least undeniably American.”

Which speaks poorly for American literature.

The buf is found in all the big eastern cities. The she ones is called a cow cause she bellows loud and shrill, but the little one he is a sucker. The buflo is a natif of Omaha, but the peoples there they said: “Oh whats the use, for the mooley cow is more milkey and cant gore.”

|

S. T. Joshi, in his introduction to The Collected Fables of Ambrose Bierce, notes that during Bierce’s expatriate days in London “...he began writing a series of ‘Fables and Anecdotes’ in the voice of an imaginary backwoods boy, Little Johnny, a character that had evidently proved popular with British readers of Fun, where Johnny had made his debut; but these ‘fables’ — written in an almost impenetrable patois of deliberate solecisms and misspellings — are so radically different from Bierce’s other work in the fable form that they have not been included here.”

Joshi also writes that the number of Little Johnny sketches are “...so voluminous that they would require a volume—perhaps several volumes—all to themselves.” An event unlikely to occur.

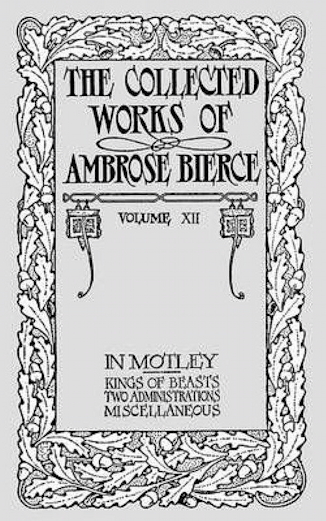

Nevertheless, Bierce did manage to include a selection of thirty-three Little Johnny tales in Volume XII of his Collected Works, under the heading “Kings of Beasts by Little Johnny (Edited to a Low and Variable Degree of Intelligibility of the Author’s Uncle Edward.” Some might say they were thirty-three tales too many.

Soljers isent animals, but they can lick the hi potamus and the tagger, and the rhi nosey rose, and evry thing which is in the world. When I grow up Ime a going for to be a soljer, and then all the fellers which I dont likes heads and say: Hooray! That will teach you that Columby is the gem of the ocean.”

|

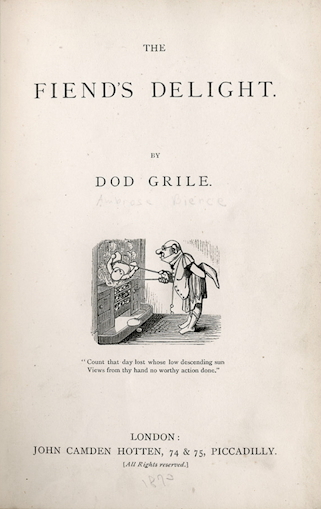

A precursor to Little Johnny appears in a short piece in The Fiend’s Delight, Bierce’s first book (1873) under the pseudonym Dod Grile. It’s not in dialect and is not narrated by Johnny himself, but it describes a four-year-old of “bright, pleasant manners, and remarkable intelligence,” who fails to answer the question: who made him?

Similarly, a Little Johnny appears in Bierce’s second book, Cobwebs from an Empty Skull (1874) under the title “Converting a Prodigal,” again not in dialect, in which Little Johnny is cheated of his savings by his older brother Charlie.

title page, Bierce's first book

After Bierce returned to America, the founder of the Argonaut, Frank Pixley, engaged Bierce to write for the weekly. It was where Bierce made his name, and where Little Johnny returned, initially written under the general heading “Little Johnny’s Menagerie.” The first appeared in the issue of January 12, 1878, and the last on October 11, 1879.

Frank Pixley

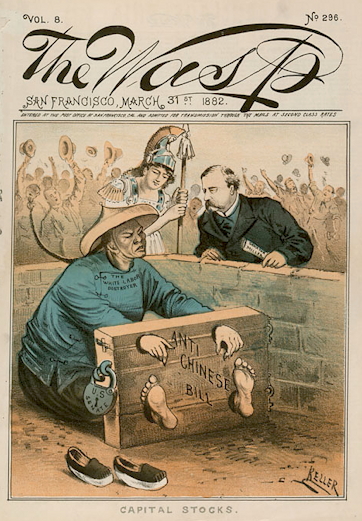

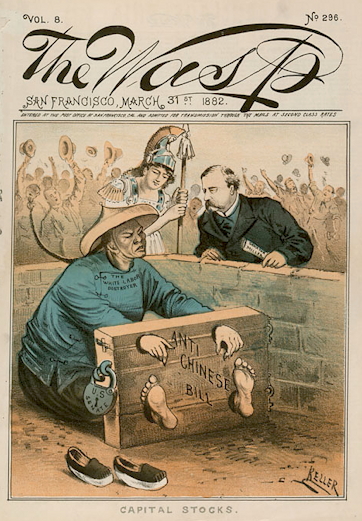

Relations between Pixley and Bierce became contentious (in doggerel, Bierce wrote of Pixley: “...must I hear you call the roll / Of all the vices that infect your soul?”), and Bierce departed to try his hand at managing a gold mining operation in Dakota Territory. When that failed, he returned to San Francisco to write for The Wasp, where he enjoyed some of his most productive years, notably his column “Prattle.” However, like a bad penny, Little Johnny returned under the heading “Fables and Anecdotes” in the issue of April 16, 1881. Scores of Little Johnny pieces appeared in The Wasp over the next five years, the last on March 13, 1886.

The Wasp

Uncle Ned he said: Johnny, do you know about the pol patriot?” I said: “Yessir, it can be tought for to talk, just like gerls, and says ‘Polly wants a cracker,’ frequent.”

|

After a brief period of unemployment, Bierce was hired by William Randolph Hearst as the San Francisco Examiner’s only bylined writer. He relaunched “Prattle,” and, sure enough, Little Johnny bounced back in the edition of July 19, 1887. Despite the Little Johnny pieces, Bierce wrote his greatest fiction during this period, including the brilliant stories that appeared in his masterwork, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians, which fortuitously did not include any Little Johnny material.

William Randolph Hearst

When Bierce relocated to Washington, DC, his Little Johnny pieces began appearing in Hearst’s New York Journal (later named the American], the first on October 12, 1901, as well as in the Examiner. The final newspaper appearance of Little Johnny was June 24, 1906, a sketch called “The New Dispensation in Mumbooglia.” (Occasionally, Hearst’s headline writers would misspell Johnny’s name “Johnnie.”)

But Bierce wasn’t through. He began writing for Hearst’s Cosmopolitan magazine, where Little Johnny at last met his end in the issue of April 1909, a story called “Little Johnny on the Dog.”

I ast my sister: “Don’t you think buzzards is awfle nasty fellers for to eat sech things as they do?” My sister she said: “What can you xpect of birds that live on a carry on diet. That’s like old Gaffer Peters, which has got the bald head. My mother she said to him: “Gaffer, the sun is mighty hot to day.”

|

One would think Bierce would have had enough of Little Johnny after all those years, but no. In a letter to Robert H. Davis, editor of Munsey’s magazine, in the summer of 1902, Bierce wrote: “...do you know of any fool publishers up there to whom you would care to suggest making a book of ‘Little Johnny’ stuff? It is the only stuff I ever wrote which I think would sell well in covers. I’ve been writing it in London, San Francisco and New York for more than thirty years, and all editors grab at it; but I’ve not had any annoyance from the eager importunities of publishers. Block [a journalist who wrote under the pseudonym of Bruno Lessing] wrote me a long time ago that I would probably get an offer from Stokes [Frederick A. Stokes, a publisher] ‘after the holidays.’ Stokes has since rejected two books of mine, but the offer for that one has not come. Don’t take any trouble in the matter, but if you happen to know personally any publisher that you’d like to do an ill turn you might mention the matter to him. Do you?”

There were no takers — until publisher Walter Neale, who was smitten, even intimidated, by Bierce, agreed to publish the author’s Collected Works in 1912; thus, a number of Little Johnny tales were slipped into Volume XII.

Collected Works, Vol. XII

That the Little Johnny stories were deliberately written in a primitive vernacular is strange because of Bierce’s own skepticism regarding oddities of speech. He cynically defined reading in America as usually consisting “of Indiana novels, stories in dialect, and humor in slang.”

There may have been a modicum of justification for the excessive use of dialect in nineteenth and early twentieth century American fiction as practiced by, yes, such Indiana authors as Booth Tarkington and James Whitcomb Riley— even Twain (see Huckleberry Finn). Before audio recordings, talkies, and radio, there was no better way to replicate American speech. Now, dialect in fiction appears dated, stilted, onerous to read, sometimes racist, and downright annoying.

Yet Bierce denied that he put actual dialect into the mouth of Little Johnny. In a letter to Myles Walsh on June 6, 1905, he wrote: “No, my lad, you never read anything of mine before I ‘joined the crowd of phonetic-spelling humorists,’ if you refer to the ‘Little Johnny’ things; they were begun in London before your birth. And [they] are not ‘phonetic spelling’ humor at all; the spelling is done for vraisemblance [verisimilitude or seeming true] and is intended to represent the actual spelling of such a kid. [italics mine] As to the ‘crowd,’ they are mostly my imitators, as far as they are able to be. I’ve seen the rise and fall of more than a hundred ‘Little Willies,’ ‘Little Sammies,’ and so forth. The American [the Hearst newspaper] has laid on a ‘Little Bobbie.’”

S. T. Joshi generously theorizes that Bierce, knowing that dialect deflected from serious art, in utilizing Little Johnny’s weird patois, may have been exploiting the ignorance of those who actually spoke in dialect: “The execrable ‘Little Johnny’ sketches he wrote for much of his career were possibly done as a mockery of popular taste...”

If it was mockery, Bierce never tired of it.

The Bible it says that fellers which are nusances shall arise from the dead. And that’s why I say eat drink and be merry, for to-morrow you don’t. But a pigs tail, nice roasted is the king of beasts.

|

******

RESOURCES

Berkove, Lawrence I. A Prescription for Adversity: The Moral Art of Ambrose Bierce

Columbus, 2002.

Bierce, Ambrose. A Much Misunderstood Man. Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce.

Edited by S. T. Joshi and David E. Schultz. Columbus, 2003.

_____________. Collected Fables. Edited by S. T. Joshi. Columbus, 2000.

_____________. Collected Works, Vol. XII. Washington, 1912.

_____________. Short Fiction of Ambrose Bierce. Edited by S. T. Joshi, David E.

Schultz, Lawrence I. Berkove. Knoxville, 2006.

Fatout, Paul. Ambrose Bierce: The Devil’s Lexicographer. Norman, 1951.

Joshi, S. T. and David E. Schultz. Ambrose Bierce: An Annotated Bibliography of

Primary Sources. Westport, 1999.

McWilliams, Carey. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. New York, 1929.

Starrett, Vincent. Ambrose Bierce. Chicago, 1920.

West, Richard Samuel. The San Francisco Wasp: An Illustrated History. 2004.

Don Swaim is the author of The Assassination of Ambrose Bierce: A Love Story, Hippocampus Press, New York

|