|

the AMBROSE BIERCE site |

by Don Swaim

________________

It never took much to get under the skin of Ambrose Bierce. A word, a comment, a misplaced idea — even by old friends — could lead Bierce to angrily sever a relationship. So it happened with the California poet Edwin Markham — although the breach between the two was more or less repaired later in their lives. Markham forgave more easily than Bierce.

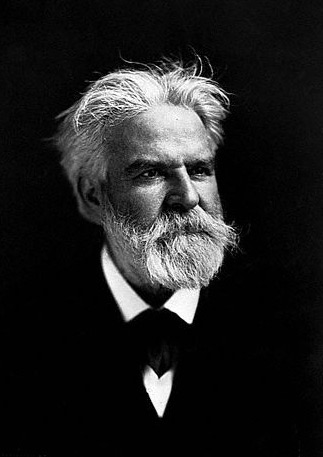

Bierce never denied Markham’s accomplishments as a poet, but in terms of politics and philosophy, the two men were far apart, and Markham committed the unforgiveable sin of writing a poem the sentiments of which Bierce profoundly, no, rabidly, disapproved. Markham’s poetic achievements are now mostly overlooked, but in his day he was widely praised, his four books of poetry republished over many editions. At the peak of his fame, Markham read his celebrated poem, “Lincoln a Man of the People,” during the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington in 1922. On the occasion of his eightieth birthday at New York’s Carnegie Hall in 1932, Markham was venerated by President Herbert Hoover along with visitors from thirty-five foreign countries. Schools throughout the nation, five in California alone, were named after Markham. It is certain that, in his lifetime, Edwin Markham never thought about zombies, yet a fanciful re-reading of some of his poetry might lead to the conclusion that Markham had anticipated the zombie craze, which has infiltrated the popular culture, (some examples below), while Bierce’s own legacy as a writer of horror and the supernatural remains lofty to this day. The Markham poem that set Bierce off was “The Man with the Hoe,” [read in its entirety here] originally published by the San Francisco Examiner, Bierce’s own newspaper. How this happened is set forth below, but, first, the events leading up to the contretemps. Markham, born in Oregon in 1852 — ten years after Bierce’s own birth — had become a school teacher and administrator in Oakland, California, and was part of a Western artistic circle that included Bierce, Hamlin Garland, George Sterling, Joaquin Miller, Jack London, and others. All along, Markham had been writing poetry, publishing his first in 1880, and was encouraged by Bierce who saw himself as the arbiter of all things literary in California. From the beginning, Markham was in awe of Bierce, saying of the older writer: “His is a composite mind — a blending of Hafiz the Persian, Swift, Poe, Thoreau, with sometimes the gleam of the Galilean.” Markham clipped Bierce’s columns from the newspaper, pasting them into a scrapbook. After he at last met his hero, Markham gushed, “I found Mr. Bierce one of the most gentle and delightful of men...a philosopher with a childlike and winged spirit and heart...a man judicious and fearless, who is clearing the air like a thunderbolt.”  Edwin Markham Bierce also admired Markham, particularly his poem, “The Wharf of Dreams.” Bierce’s first major biographer, Carey McWilliams, said the poem was Bierce’s favorite sonnet: Strange wares are handled on the wharves of sleep: What happened that led such mutual admiration to crumble? Bierce would be described today as a libertarian, the struggles of the poor of little interest to him. But inside Markham’s chest beat the heart of a man with a profound social conscience. Jesse Sidney Goldstein, in an essay published in Modern Language Notes in 1943, put it this way:

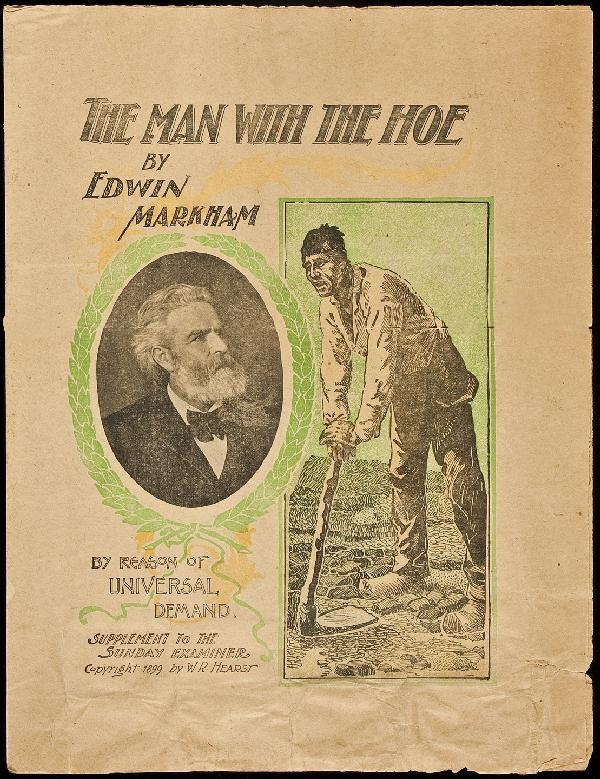

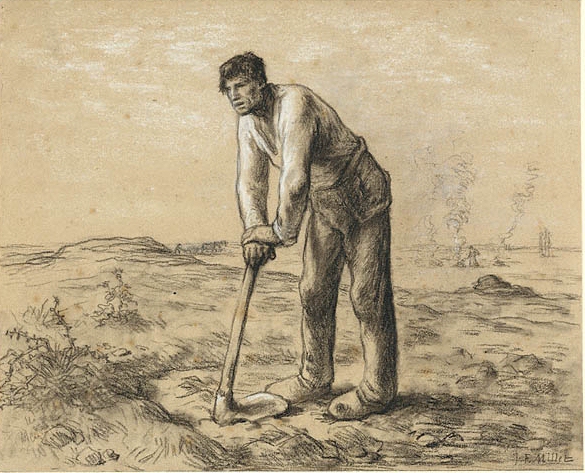

Bierce, of course, had no patience with so-called socialistic notions, although what was considered as socialism then is commonly accepted in America today as the byproduct of a humane, progressive society: Social Security, for example, or Medicare, even food stamps. Bierce’s long-running feud with Jack London, an ardent socialist, was ended only by a mutual admiration for alcoholic spirits. In The Wasp in 1884, Bierce wrote: Let Socialists make the laws today and they would break them tomorrow. No sooner do the poor become rich than they harden their hearts to the miseries of the poor. In so far as it proposes to correct the evils of unequal fortune, Socialism aims to repeal the laws of nature. At a New Year’s eve party at the home of Carroll Carrington [another Bierce protégé] on the last day of 1898, Markham read his newly-conceived poem, “The Man with the Hoe,” inspired by Jean-Francois Millet’s painting of a world-wearied laborer standing, hunched, in a barren field. For Markham, the man in the painting symbolized the suffering of the oppressed workingman throughout history. Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans As he recounted later, Markham said that after he read his poem at the party, there was no applause whatsoever. In fact, there were two minutes of utter silence. Then the literary editor of the San Francisco Examiner, Bailey Millard, who was in the crowd, asked to see the typewritten poem. He read it twice, then announced, “That poem will go down the ages.”

San Francisco Examiner, January 15, 1899 Markham later wrote: Letters began to pour into the newspapers — some attacking the poem, others defending it. It was attacked from all points of view — theological, biological, geological, chronological, anthropological, zoological, phrenological. Thousands of men, ranging all the way from professors to plowmen, gave vent to their pent-up feelings in voluminous letters. William Jennings Bryan called it a “sermon addressed to the human heart.” Railroad robber baron Collis P. Huntington asked, “Is America going to turn to Socialism over one poem?”

My chief objection relates to the sentiment of the piece...the thought is that of the Sandlot... The notion that the sorrows of the humble are due to the selfishness of the great is “natural,” and can be made poetical, but it is silly. As a literary composition it has not the vitality of a sick fish. Bierce would not let it go, particularly as “The Man with the Hoe” continued to gain notoriety. On February 12 in the Examiner, Bierce condemned Markham of holding “peasant philosophies of the workshop and the field.” And in a personal letter to Markham dated March 14, 1899, Bierce accused the poet of: ...preaching a doctrine of hate, which has successfully appealed to the worst side of human nature. I don’t think you quite knew that you were doing so; but you know how, and I hope you will no longer dwell in the tents of the demagogue, nor preach vague dreams to the cranks of that association - what’s its name? In the Examiner on June 4, he again denounced Markham as a demagogue, and called him: ...a “labor leader” spreading that gospel of hate known as “industrial brotherhood,” a “walking delegate” diligently inciting a strike against God and clamoring for repeal of the laws of nature... He appears at meetings of cranks...convened to shriek against the creed of law and order.... When not waving the red flag and beating the big drum I presume he is resting the flexors of tongue and arm. In letters to friends, Bierce complained that Markham had taken to cant and snivel, was an unsaddled Pegasus who straddled the flying jackass of the sandlot, who followed the Boer War with an attitude pro-British, anti-Dutch, and semi-decent. He claimed that Markham’s lucid intervals were all too rare. In a letter to the poet George Sterling dated December 16, 1901, Bierce warned Sterling not to follow in Markham’s footsteps: If you do I shall have to part company with you, as I have done with him and at least one of his betters, for I draw the line at demagogues and anarchists, however gifted and however beloved. In a letter to Sterling dated May 6, 1906, Bierce [who by this time had moved to Washington while Markham had moved to New York City] wrote: “I never see Markham, and he has lost his interest to me since he has made a whore of his Muse for the wage of the demagogue. As a poet he was great; as a ‘labor leader’ and ‘walking delegate’ he disgusts.”

During all my early manhood I was a workingman under hard and incorrigible conditions. The smack of the soil and the whir of the forge are in my blood. I know every coign and cranny of ranch and range. The breaking of the ground with the plow, the sowing and harrowing of the seed, the watching of the skies for omens of the weather, the heading and threshing of the wheat, the piling of the hay-mows — I know all these things. Markham saw his hoeman as: ...the symbol of betrayed humanity, the toiler ground down through ages of oppression, through ages of social injustice.... He is the man pushed back and shrunken up by the special privileges conferred upon the few.... It is not the poverty of the hoeman that I deplore, but the impossibility of escape from its killing frost.  Millet sketch for The Man with the Hoe Bierce became more insular as he aged, but not so Markham, who spoke against injustice and made child labor a personal crusade, lashing out against what he branded as a moral crime in a book entitled Children of Bondage published in 1914.

_______________________________________________ Among the Sources: Bierce, Ambrose. A Much Misunderstood Man: Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce. S.T. Joshi, David Schulz, eds. Columbus, 2003. Fatout, Paul. Ambrose Bierce: The Devil’s Lexicographer, Norman, OK, 1951. Goldstein, Jesse Sidney. “Ambrose Bierce and the Man with the Hoe,” Modern Language Notes, 1943. Markham, Edwin. The Man with the Hoe and Other Poems. Garden City, 1921. ______________. “Markham’s Reflections on Writing ‘A Man with the Hoe.’” Modern American Poetry. University of Illinois, Urbana. www.english.illinois.edu. McWilliams, Carey. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. New York, 1929. Slade, Joseph W. III. “Edwin Markham [1852-1940]” Modern American Poetry. University of Illinois, Urbana. www.english.illinois.edu. © 2011 Don Swaim

|