|

The Parrot That (Almost) Ruled the World

by Don Swaim

The American Mercury, inaugural issue, January 1924

He was a damned fraud.

It’s strange to be making such an assertion about Ambrose Bierce ten years after his bizarre disappearance in Mexico—but now is past the time to tell the truth about him. While Bierce is thought to have been one of the most prolific writers in all of American literature, the facts are otherwise, and now the lies and exaggerations by and about him must be exposed. H.L. Mencken, co-founder of The American Mercury, has allowed—nay, encouraged—me to express the entire story in the pages of this newly-formed journal endowed by the generosity of publisher Alfred A. Knopf.

That Bierce was both duplicitous and a cad cannot be overstated, even when taking into account my eventual antipathy toward him, far different from the way the two of us began. Yet it was I, mostly, who precipitated the conflict, so I must accept my share of the blame.

These things I know, not by rumor or allegation or from the rantings of his many critics, but because of my first-hand knowledge. I was a near constant in his presence until that day in 1913 when he left Union Station in Washington, DC, on his fateful journey to Mexico.

The facts are these.

I first met Bierce in San Francisco in November 1866 shortly after he arrived and well before he established himself as a writer. At the time, he was working as a night watchman at the U.S. Mint on Commercial Street, just west of Montgomery.

A coworker of Bierce’s at the Mint brought us together. At first, Bierce saw me as a minor influence in his life, someone he could blithely cast aside as, say, an unwanted pet. But our relationship would change, and it is certain that he would not have achieved his renown without me.

At the time we met, Bierce, as a heroic Union veteran of the Civil War, was struggling, his dream of being commissioned a captaincy in the peace-time army unfulfilled. During his restless days, before returning to the Mint for his night-time labors, he would compose trivial little poems and tales, all negligible and depthless, and all unpublished. With his hoped-for military career dashed, he had scant expectations, but, with few skills other than the military and with only a short stint as a printer’s devil on an Indiana weekly, he entertained the notion that he might become an author—if only he knew how and what to write.

I had first been associated with our mutual acquaintance, a former Bostonian named Tinley Roquot, who worked in the Mint’s Smelting Department. Roquot was both brainy and unprincipled. He adored books and possessed them by the hundred, although they had all been purloined from the public library in Pacific Hall, the private libraries at the Mercantile Association and the Mechanics Institute, as well as the personal libraries of Leland Stanford and Hubert Howe Bancroft. With those resources, he set about educating me, and it wasn’t long before I became more canny than Roquot himself.

“I’ve unleashed a monster,” he once proudly asserted to me.

But he didn’t just steal books. At the Mint, he plundered coins of all denominations before they could be melted down, and recirculated them from his own pockets. Double eagles, eagles, half eagles, quarter eagles, gold and silver dollars. Tinley Roquot was smart, but not so much that he couldn’t get caught, which led to a twenty-year sentence at the state leisure facility of San Quentin.

U.S. Mint

Roquot knew that his new-found chum, Bierce, favored small pets—lizards, turtles, and such—so when Roquot was dispatched in chains to Marin County, Bierce agreed to care for his pet parrot, Jum. Roquot had been obsessed with Jum, feared for its fate, and was desperate to find it a home.

This is when I now come clean and explain how I came to live with Ambrose Bierce.

His first published work appeared in the Californian, a poem called “The Basilica,” which originally read:

With aimless feet, along the verge

Of ocean, where the rocks emerge,

I strolled, and watched the driving surge.

It might have been better, which was my fault. I should have devoted more attention to it. But the fact that it would be published at all encouraged him to continue—and for me to make that happen.

I told him, “I dislike your using the word ‘driving’ to describe the surge.”

“What’s wrong with it?”

“It’s common. Utilize a more poetic expression, such as ‘baffled.’”

“I’m a purest when it comes to language. A surge is literally water in action. Only animals and humans can be baffled, as in perplexed—not waves.”

“But poetry applies metaphor and simile, such as, ‘an angry sea.’ If you prefer to be literal, write a tract on oceanography instead of the poetic arts.”

“What the hell do you know, Jum? You’re only a parrot. Just because you can talk...”

Which was true then just as much as it is now.

Jum

At first, Bierce refused to take me seriously, believing that I, even as an African gray, possessed the mere rudiments of intelligence and was purely imitative, despite my inordinate ability to communicate verbally in ways he never expected. That I preferred to eat seeds, nuts, and fruit, and never spiritous liquors as did he, was not in my favor, nor was my tendency to shit when and wherever was convenient, which I considered a fringe benefit. I also excelled at calculus and similarly my ability in English grammar, as well as French, German, Spanish, and Belarussian, although the latter with a noticeable dialect. My brain, despite its compact size, was a veritable repository of data—if not always wisdom.

His austere room was not far from the Mint, and when I first saw it I was devastated. It contained only a narrow bed, rickety chair, an overturned box for a desk, and a few books. Quite a letdown from Tinley Roquot’s well-appointed rooms. Of course, Roquot was a crook. Bierce’s only artifact seemed to be his childhood collection of arrowheads.

“This place is a dump,” I told him.

“It’s all I can afford.”

“It doesn’t even have a commode.”

“It’s down the hall. Besides, why would you need a commode?”

“How can you make me live in such squalor?”

“Oh, stop your squawking, Jum. It’s temporary until I can earn enough to improve my surroundings. Anyway, I won’t be taking guff from some bird. And how is it that you speak so fluently?”

“A simple explanation,” I replied.“My syrinx, which is at the base of the trachea, consists of two lateral tympaniform membranes controlling sound frequency. This allows for directed air to flow into my interclavicular air sacs, the pressure of which permits me to control my vocal range.”

“I knew that.”

Highly doubtful, but Bierce was unlikely to express weakness, either in knowledge or character.

He said, “You’re not even a particularly attractive parrot. Not a single feather with color except for a little red fringe on your ass.”

“Fine feathers make not the bird, my friend.”

As a much younger man, our now incarcerated acquaintance, Tinley Roquot, had won me in a drunken, marathon game of fan-tan in Chinatown’s Hang Wah Alley, and was immediately impressed by my ability to articulate far better than the troubled family in Placerville he had abandoned.

Fan-tan, Chinatown—Roquot in brimmed hat at edge of table

Initially, I hated my confinement. At fleeting times I craved escape, but eventually adjusted to captivity, cognizant that the world outside was chaotic and dangerous. For example, the entire bird population was keenly aware of what was happening to the passenger pigeon. I was also conscious of the fact that I was small and vulnerable, impossible for me to compete on a physical level, a juicy target for owls, vultures, and humans with rifles. So I focused on study, knowledge, stratagem, and tactics, my major regret being that I would never be the chess player I wanted to be.

Tinley Roquot trained me, and for that I give him credit. He read aloud to me at every waking hour from the plethora of books he had excessively and illegally acquired. He even engaged an astute neighboring urchin to read to me in those periods when he was at the Mint or out burgling. In time, it was clear that my ability to absorb raw information far surpassed my owner’s, at which point it became uncertain as to who owned whom.

Now, with Tinley Roquot behind bars, I was the companion of Ambrose Bierce, which would prove to be a more suitable match—although often volatile, acerbic, and hostile.

Still, he read to me from all of the current journals and newspapers, so I was able to keep abreast of the times. When he launched a regular column in the various journals he wrote for over the years, I was able to dictate to him his copy, which he published verbatim knowing that my command of both fact and language far exceeded his own.

“How did you become so smart, Jum?” he asked in a moment of familiarity borne of Martell VSOP.

“It wasn’t always that way. In my younger days I had to wing it.”

“And how much more do you need to know before you can rule the world?”

He made the question sound like a joke, but I suspect deep in his intellect he believed it.

“I know enough now, Ambrose. But, as you say, I’m only a parrot. And, admittedly, my hygiene isn’t always what it might be.”

“I’ve always viewed slang as the grunt of a human hog with an audible memory. In other words, the speech of one who utters with his tongue what he thinks with his ear, and feels pride in accomplishing the feat of a parrot. Although it your case, Jum, I’ve changed my mind about parrots.”

I maintained an unassuming distance after his marriage to Mollie Day, but joined them when they sailed to England. In London, I guided his regular column “The Passing Show,” and wrote his first three books, which he published under the pseudonym of Dod Grile.

When he and Mollie returned to America, I helped Bierce launch a new column,“Prattle,” in the Argonaut. Taking leave to go to the Black Hills to supervise an ill-fated gold mining operation, he took me with him, and I became an expert on hydraulic drilling.

Back in California, he resumed his column, this time in The Wasp, which led to a stint on the San Francisco Examiner and his ambivalent relationship with William Randolph Hearst.

When I noticed that Bizet’s Carmen was being performed at Maguire’s Opera House on Washington Street, I begged Bierce to take me.

“I’m not taking a parrot to the opera.”

“I insist.”

“Parrots aren’t allowed at Maguire’s. There’s a sign on the front door.”

“That’s a falsehood, and you know it. The sign reads ’No Chinese.’ I must see a performance of Carmen. I demand it.”

“Stop ruffling your feathers. Why do you want to go to that opera anyway?”

“I liked the book.”

McGuire’s Opera House

Due to me, Bierce and I were highly productive during this period and produced some of the best-known material attributed to him, including what may be my finest effort, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.”

I told him, “Ambrose, I don’t care for the way you adjusted the ending in this story. It’s not the way I wanted it.”

“There’s nothing wrong with my ending. I know this period. I saw firsthand what was done to traitors and spies in the war.”

“But you merely have the escaped spy, Payton Farquhar, arriving safely at home to his wife and children after successfully eluding his Yankee executioners.”

“So what? It’s the way it happened. I know. I was in that place while you were still in a cage somewhere, defecating.”

“But you’ve cobbled a trite ending to an otherwise decent story, potentially our most significant.”

“How should I end it?”

“By having Payton Farquhar believing in his freedom even as the executioners’ rope snaps his neck.”

A pause.

“I’ll think about it.”

And I created all of the definitions in The Devil’s Dictionary, including my favorite:

Fraud, n. The life of commerce, the soul of religion, the bait of courtship, and the basis of political power.

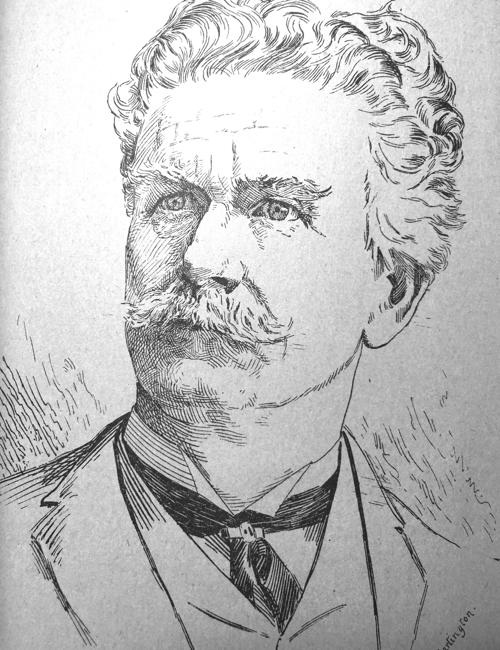

Ambrose

When Bierce went East to muckrake for Hearst’s newspapers, I was with him, providing the strategy he and Hearst used to blunt the avaricious influence of the railroad interests. I must, however, give Bierce credit for inventing the term “the railrogues.”

But occasionally, he would go off his tether and write material I disapproved of, such as a series of lame stories composed in dialect ostensibly by an uneducated little boy.

I told him, “Ambrose, those awful ‘Little Johnny’ stories you invented are doing our reputation no good. They’re not even funny.”

“What do you know?” he said with a snarl. “You’re only a parrot.”

His parrot line had become an almost ritualized joke between us, although becoming less and less funny.

“Listen, Jum, you may think you know a lot, but it wouldn’t have been possible without me. You don’t even have thumbs. I ought to charge you—if only for room and board.”

“Just put it on my bill.”

I think Bierce loved me as much as he could love anyone or anything. While he rarely displayed his emotions, he abundantly unleashed scorn and cynicism. Over the years, the volatility of our debates became more tempered, and despite occasional flare-ups, almost passive. Perhaps he was afraid of losing me, particularly as his volatility cost him both friends and an abundance of acolytes waiting in line for his blessing.

Then in Washington, he abruptly announced to me that he planned to go to Mexico to join Pancho Villa’s revolution, a scheme he had never discussed with me before. It came as a shock.

“I forbid it,” I told him. “You’re too old, Ambrose. You’ll die of some loathsome disease—if Villa doesn’t put you before a firing squad first. You’re dependent on me. Besides, I need you here. Who would clean my cage?”

“I should remain here so you can continue to take credit for my work? Which, I remind you, has now been collected in an elaborate twelve-volume set.”

“Which nobody can afford. Put out by some renegade publisher at seventy-two dollars a set, a hundred and twenty if it’s autographed. There wouldn’t even be such a body of work with your name on it without yours truly. Ambrose, you owe me.”

“And without me you’d be just another talking parrot spouting oddments, amusing party guests, and shocking virgins. It’s envy on your part, Jum, and envy is emulation adapted to the meanest capacity.”

“Hey, I wrote that.”

“Sometimes, you make me so choleric I’ve thought about opening your cage door and the window at the same time and ushering you out with a broom. Are you familiar with the term parricide?”

“From the Latin: parricidium.”

“It means doing away with a loudmouth, domineering parrot.”

“As usual, Ambrose, you have it wrong. It refers to the deliberate killing of one’s own parents.”

“What do you know? You’re only a parrot.”

“Up yours.”

“Damn you, Jum. You’ll not dissuade me from going to Mexico.”

“Then take me with you.”

“The hell I will.”

“You don’t speak Spanish. I’ll be your interpreter.”

“For the first time since you came into my life, I need to go off and do something I can call my own.”

“Impossible. And you’ll perish without me.”

“Adios, amigo.”

I had known it would all have to end someday, of course. Neither man nor bird live forever.

He left me in the custody of Carrie Christiansen, his live-in secretary—he and Mollie long divorced and she now dead. Carrie disliked me, jealous of my relationship with Bierce. And she hated my voice, although I imitated several including Bierce’s. Admittedly, I would often apply one of my most grating voices simply to annoy her.

I was confined in the dark, literally, stuck most of the time in a covered cage in the rooms she had shared with Bierce at the Olympia apartments on Euclid Street NW. Isolated from virtually all human contact, I now had no one to read to me, no one to talk to, no one to keep me abreast of the latest books and the world stage. The imbecile who created the phrase free as a bird did not know what he was talking about.

Effectively abandoned by humans, except at my irregular feedings, I was forced to pass the days by recounting in my mind the voluminous number of books I had digested over the years: Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Homer, Aristotle, Cicero, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dante, Dickens, Carlisle, Milton, Euclid, James Whitcomb Riley. When that became repetitious I would entertain advanced Euclidean algorithms and unconventional trigonometric computations.

I never learned until much later that Bierce had disappeared in Mexico.

I was about to go mad until one day Carrie unexpectedly turned me over to a nosey, fawning Illinois newspaper man, Vincent Starrett, Bierce’s most ardent fan, who took me to Chicago, where he worked for the Daily News.

Starrett

It was there Starrett learned the truth about Bierce when I opened up non-stop, proving my claims by directly reciting each and every piece written under Bierce’s byline. I was angry. Resentful. After all I had accomplished for him, and he had jettisoned me in favor of some startlingly misguided sense of adventure that I, above all, knew would end badly. And even worse was the fact that he wouldn’t take me with him.

Starrett had already published a slim, nearly useless biography of Bierce and a bibliography.

“But I’ll be damned if I’m going to change a word,” he told me. “Bierce will be made a laughing stock, and me as well. Imagine. A parrot...”

Yet I cajoled and badgered him until the newspaperman in him relented.

He said, “Perhaps I should get another opinion. I happen to know H.L. Mencken, the nation’s most important critic and public intellectual. He was acquainted with Bierce as well. Couldn’t abide the man, by the way. Dammit, I’ll let Mencken decide.”

And so it is that you are now reading my tale in Mencken’s inaugural issue of The American Mercury.

It’s the truth about Ambrose Bierce, who once defined truthful as “dumb and illiterate.” Or did I write that?

Don Swaim is the author of The Assassination of Ambrose Bierce: A Love Story, Hippocampus Press, and Deliverance of Sinners: Essays and Sundry on Ambrose Bierce, Eratta Press

Top of Page

|

|

|